Eyewitness testimony is a legal term that refers to an account given by people of an event they have witnessed.

For example, they may be required to describe a trial of a robbery or a road accident someone has seen. This includes the identification of perpetrators, details of the crime scene, etc.

Eyewitness testimony is an important area of research in cognitive psychology and human memory.

Juries tend to pay close attention to eyewitness testimony and generally find it a reliable source of information. However, research into this area has found that eyewitness testimony can be affected by many psychological factors:

- Anxiety / Stress

- Reconstructive Memory

- Weapon Focus

- Leading Questions (Loftus and Palmer, 1974)

Anxiety / Stress

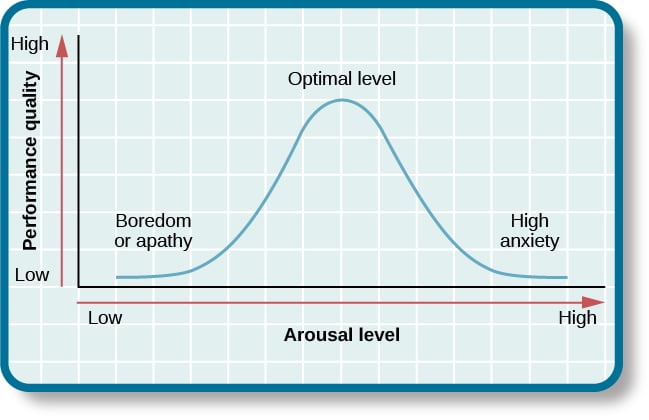

Anxiety or stress is almost always associated with real-life crimes of violence. Deffenbacher (1983) reviewed 21 studies and found that the stress-performance relationship followed an inverted-U function proposed by the Yerkes-Dodson Curve (1908).

This means that for tasks of moderate complexity (such as EWT), performance increases with stress up to an optimal point where it starts to decline.

Clifford and Scott (1978) found that people who saw a film of a violent attack remembered fewer of the 40 items of information about the event than a control group who saw a less stressful version. As witnessing a real crime is probably more stressful than taking part in an experiment, memory accuracy may well be even more affected in real life.

However, a study by Yuille and Cutshall (1986) contradicts the importance of stress in influencing eyewitness memory.

They showed that witnesses of a real-life incident (a gun shooting outside a gun shop in Canada) had remarkable accurate memories of a stressful event involving weapons. A thief stole guns and money, but was shot six times and died.

The police interviewed witnesses, and thirteen of them were re-interviewed five months later. Recall was found to be accurate, even after a long time, and two misleading questions inserted by the research team had no effect on recall accuracy. One weakness of this study was that the witnesses who experienced the highest levels of stress where actually closer to the event, and this may have helped with the accuracy of their memory recall.

The Yuille and Cutshall study illustrates two important points:

1. There are cases of real-life recall where memory for an anxious / stressful event is accurate, even some months later.

2. Misleading questions need not have the same effect as has been found in laboratory studies (e.g. Loftus & Palmer).

Reconstructive Memory

Bartlett’s theory of reconstructive memory is crucial to an understanding of the reliability of eyewitness testimony as he suggested that recall is subject to personal interpretation dependent on our learned or cultural norms and values, and the way we make sense of our world.

Many people believe that memory works something like a videotape. Storing information is like recording and remembering is like playing back what was recorded. With information being retrieved in much the same form as it was encoded.

However, memory does not work in this way. It is a feature of human memory that we do not store information exactly as it is presented to us. Rather, people extract from information the gist, or underlying meaning.

In other words, people store information in the way that makes the most sense to them. We make sense of information by trying to fit it into schemas, which are a way of organizing information.

Schemas are mental “units” of knowledge that correspond to frequently encountered people, objects or situations. They allow us to make sense of what we encounter in order that we can predict what is going to happen and what we should do in any given situation. These schemas may, in part, be determined by social values and therefore prejudice.

Schemas are, therefore capable of distorting unfamiliar or unconsciously ‘unacceptable’ information in order to ‘fit in’ with our existing knowledge or schemas. This can, therefore, result in unreliable eyewitness testimony.

Bartlett tested this theory using a variety of stories to illustrate that memory is an active process and subject to individual interpretation or construction.

In his famous study “War of the Ghosts”, Bartlett (1932) showed that memory is not just a factual recording of what has occurred, but that we make “effort after meaning”.

By this, Bartlett meant that we try to fit what we remember with what we really know and understand about the world. As a result, we quite often change our memories so they become more sensible to us.

His participants heard a story and had to tell the story to another person and so on, like a game of “Chinese Whispers”.

The story was a North American folk tale called “The War of the Ghosts”. When asked to recount the detail of the story, each person seemed to recall it in their own individual way.

With repeating telling, the passages became shorter, puzzling ideas were rationalized or omitted altogether and details changed to become more familiar or conventional.

For example, the information about the ghosts was omitted as it was difficult to explain, whilst participants frequently recalled the idea of “not going because he hadn’t told his parents where he was going” because that situation was more familiar to them.

For this research, Bartlett concluded that memory is not exact and is distorted by existing schema, or what we already know about the world.

It seems, therefore, that each of us ‘reconstructs’ our memories to conform to our personal beliefs about the world.

This clearly indicates that our memories are anything but reliable, ‘photographic’ records of events. They are individual recollections which have been shaped & constructed according to our stereotypes, beliefs, expectations etc.

The implications of this can be seen even more clearly in a study by Allport & Postman (1947).

When asked to recall details of the picture opposite, participants tended to report that it was the black man who was holding the razor.

Clearly this is not correct and shows that memory is an active process and can be changed to “fit in” with what we expect to happen based on your knowledge and understanding of society (e.g. our schemas).

Weapon Focus

This refers to an eyewitness’s concentration on a weapon to the exclusion of other details of a crime. In a crime where a weapon is involved, it is not unusual for a witness to be able to describe the weapon in much more detail than the person holding it.

Loftus et al. (1987) showed participants a series of slides of a customer in a restaurant. In one version, the customer was holding a gun, in the other the same customer held a checkbook.

Participants who saw the gun version tended to focus on the gun. As a result, they were less likely to identify the customer in an identity parade those who had seen the checkbook version

However, a study by Yuille and Cutshall (1986) contradicts the importance of weapon focus in influencing eyewitness memory.

References

Allport, G. W., & Postman, L. J. (1947). The psychology of rumor. NewYork: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Bartlett, F.C. (1932). Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Clifford, B.R. and Scott, J. (1978). Individual and situational factors in eyewitness memory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63, 352-359.

Deffenbacher, K. A. (1983). The influence of arousal on reliability of testimony. In S. M. A. Lloyd-Bostock & B. R. Clifford (Eds.). Evaluating witness evidence . Chichester: Wiley. (pp. 235-251).

Loftus, E.F., Loftus, G.R., & Messo, J. (1987). Some facts about weapon focus. Law and Human Behavior, 11, 55-62.

Yerkes R.M., Dodson JD (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18: 459–482.

Yuille, J.C., & Cutshall, J.L. (1986). A case study of eyewitness memory of a crime. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 291-301.