In psychology, a false memory refers to a mental experience that’s remembered as factual but is either entirely false or significantly different from what actually occurred.

These can be small details, like misremembering the color of a car, or more substantial, like entirely fabricated events. They can be influenced by suggestion, misattribution, or other cognitive distortions.

Key Takeaways

- False memory is a psychological phenomenon whereby an individual recalls an actual occurrence substantially differently from how it transpired or an event that never even happened.

- Interference, leading questions, obsessive-compulsive disorder, false memory syndrome, and sleep deprivation can cause false memories.

- Pioneered by the work of Sigmund Freud and Pierre Janet, research on false memory has immensely benefitted from the contributions of the American cognitive psychologist Elizabeth F. Lotus.

- False memory has manifold real-world implications ranging from false convictions in court proceedings to accidental manslaughter.

False memory is a psychological phenomenon whereby an individual recalls an event that never happened, or an actual occurrence substantially differently from the way it transpired.

In other words, a false memory could either be an entirely imaginary fabrication or a distorted recollection of an actual event. Moreover, false memories are distinct from simple errors in recollection.

Firstly, an individual who holds a false memory maintains some certitude in the veracity of the memory. Secondly, a false memory deals not with forgetting something that actually happened but with remembering what had never taken place.

Instances of this phenomenon may range from the mundane—such as remembering that you ate breakfast when you actually did not, to the serious—such as falsely recalling that your boss assaulted you.

Examples of False Memory

- Recalling a childhood trip to Disneyland that never actually happened.

- Remembering being lost in a mall as a child, even if this event didn’t occur.

- Misremembering the details of a crime scene after being influenced by leading questions or post-event information.

- Believing that you locked the door before leaving home when you didn’t.

- Remembering a word or item from a list that was never presented because it was similar to the presented items.

- Confusing the source of information, such as believing a dream event happened in reality.

- Remembering that a news event was reported on one channel when it was actually reported on a different one.

Mandela Effect

The Mandela Effect is a phenomenon where a large group of people remembers an event or detail one way, but it actually occurred differently.

It’s named after the instance where many people falsely remembered that Nelson Mandela died in prison in the 1980s, while he actually passed away in 2013.

This collective misremembering is an example of false memory, highlighting how memory isn’t perfect and can be influenced by societal factors, misinformation, or misconceptions.

Causes of False Memories

False memories can stem from a variety of sources. Following are some of them.

Interference

The distortion of the memory of the original event by the new information can be described as retroactive interference (Robinson-Riegler & Robinson-Riegler, 2004).

In other words, the new information interferes with the ability to preserve the formerly encoded information. The effect of misinformation, which has been a subject of investigation since the 1970s, demonstrates two significant shortfalls of memory (Saudners & MacLeod, 2002).

Firstly, the weakness of suggestibility reveals how others’ expectations can shape our memory. Secondly, the drawback of misattribution unveils how the memory can misidentify the origin of a recollection.

These findings have raised serious concerns about the reliability and permanence of memory.

Leading Questions

Misleading information is incorrect information given to the witness, usually after the event. It can have many sources, for example, the use of leading questions in police interviews, or it can be acquired by post-event discussion with other witnesses or other people (Weiten, 2010).

When the eyewitnesses of an event are questioned immediately following the pertinent incident, the memorial representation of what had just transpired could be significantly altered (Loftus, 1975).

Leading questions are questions that are asked in such a way as to suggest an expected answer. For example: Did you see the man crossing the road?

The word “the” suggests that there was a man crossing the road. A non-leading question in this case could have been, “Did you see anybody crossing the road?”

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

It is possible for individuals suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) to have memory deficits or poor confidence in their memories (Robinson, 2020).

This disorder, which can stem from the abnormal responses of certain brain regions to serotonin, is a condition characterized by irrational and excessive urges to act in certain ways as well as give into repetitive and unwanted thoughts.

Because individuals with this condition are less likely to have confidence in their own memories, they are more likely to create false memories, which in turn, lead to compulsive and repetitive behaviors.

False Memory Syndrome

False memory syndrome is a condition in which an individual’s identity and relationships are influenced by factually incorrect recollections which are, nonetheless, strongly believed (McHugh, 2008; Schacter, 2002).

This condition may result from the controversial recovered memory therapy, which utilizes various interviewing techniques such as hypnosis, sedative-hypnotic drugs, and guided imagery to supposedly help patients recover forgotten memories that are purportedly buried in their subconscious minds.

Sleep Deprivation

Sleep is considered to provide the optimum neurobiological conditions conducive to the consolidation of long-term memories (Diekelmann, Landolt, Lahl, Born & Wagner, 2008).

Moreover, sleep deprivation is known to acutely impair the retrieval of stored recollections.

One study tested whether false memories could be invented based on a consolidation-related reorganization of new memory representations over post-learning sleep or as an acute retrieval-associated phenomenon induced by sleep deprivation during memory testing.

The results suggested that sleep deprivation at retrieval could enhance false memories. However, the administration of caffeine prior to retrieval was found to offset this effect.

This may imply that adenosinergic mechanisms could help generate false memories, which are associated with sleep deprivation.

Research

The initial research on false memory was pioneered by Sigmund Freud and Pierre Janet (Gleaves, Smith, Butler & Spiegel, 2006). Even though Freud’s assertions on psychoanalysis have been discredited by many, his emphasis on memory continues to elicit attention (Knafo, 2009).

Moreover, Janet Pierre’s discussion of memory retrieval via hypnosis and dissociation continues play a foundational role in the field of false memory (Zongwill, 2019). The most significant contributions to the research on false memory, however, seemed to have begun with the work of the American cognitive psychologist Elizabeth F. Lotus.

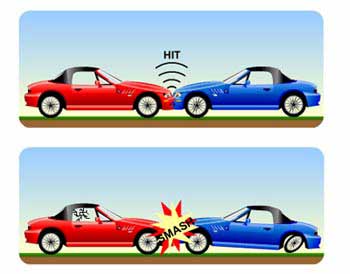

In 1974, Elizabeth Loftus and John C. Palmer conducted two experiments in which the participants viewed videos of automobile accidents and answered follow-up questions (Loftus & Palmer, 1974).

The question inquiring how fast the automobiles were moving when they ‘smashed’ into each other procured higher estimates of speed than the queries that employed verbs such as ‘bumped,’ ‘contacted,’ ‘collided,’ or ‘hit,’ instead of ‘smashed.’

Furthermore, a week later, the subjects who had received the question containing ‘smashed’ were more likely to indicate that they had also seen broken glass in the scene, although the video did not show any broken glass. These results seemed to imply that the questions asked following an event could add falsity to one’s memory of that event.

Another research study conducted more recently by Kathryn Braun, Rhiannon Ellis, and Elizabeth Loftus explored whether autobiographical advertising used by marketers to induce nostalgia for products could cause people eventually believe that they themselves had had the experiences demonstrated in the advertisements (Braun, Ellis & Loftus, 2002).

In the study, the subjects viewed advertisements suggesting that they had shaken hands with either Mickey Mouse or some imaginary character. In both instances, the ads seemed to enhance the confidence of the subjects that they had actually shaken hands with these characters.

While the encounter with Mickey Mouse could be true, the experience with the imaginary character could not be true [since the character had been invented solely for the study]. These results seemed to demonstrate that autobiographical referencing, especially in advertisements, could create distorted or false memories in the minds of the viewers.

Another study examined the links among the techniques and procedures to which false memory describes outcomes (Bernstein, Scoboria, Desjarlais & Soucie, 2018).

These procedures and techniques include subscribing to the belief that the false event transpired, accepting the misinformation following the event, and recognizing the crucial lures in the DRM (Deese-Roediger-McDermott) procedure.

The results seemed to suggest that a statistically reliable yet weak correlation may be present between the suggestion of the false event and misinformation following the event and between the DRM intrusions and the misinformation following the event.

The correlation between the suggestion of the false event and the DRM intrusions, however, seemed inconsistent as well as weak.

The outcome of the study implies that the abovementioned effects are shaped by underlying independent mechanisms, and that the term false memory wants precision and needs qualification.

Real-World Implications

Despite the obvious shortfalls of memory, people often assume that recollections of stressful and violent events are encoded well enough for effective and accurate retrieval (Lacy & Stark, 2013).

However, evidence from neuroscience studies and psychological research demonstrate that memory embodies a reconstructive process which is vulnerable to distortion. Consequently, common misunderstandings—such as, that memory is more reliable than it actually is, can lead to serious consequences especially in courtroom settings.

The case Ramona v. Isabella, for instance, dealt with a supposedly false memory implanted by two therapists in their patient, Holly Ramona (La Ganga, 1994).

Her father, Gary Ramona, successfully sued the two psychiatrists whom he accused of having implanted memories of incestual abuse into his daughter following the administration of sodium amytal (a hypnotic drug).

In 1994, the jury voted 10-2 in favor of the father, who was also awarded $500 000 corresponding to the damages and losses he had suffered following the false allegation that he sexually abused his daughter.

In another incident, a woman named Lyn Balfour was charged with second-degree murder, child abuse, felony, and neglect for leaving Bryce, her nine-month-old son, to die in a hot car (Balfour, 2012).

Following a thorough investigation, however, the jury determined that Balfour was not guilty of murder.

Conversely, it was concluded that she had had the false memory of dropping off her son at the babysitter’s, which she was in the habit of doing as part of her routine.

Learning Check

Which of the following is most likely to be a false memory?

- Remembering that you brushed your teeth this morning. (Unlikely)

- Recalling the exact words of a conversation you had a year ago. (Possible)

- Remembering the color of your childhood friend’s bicycle. (Possible)

- Recalling being abducted by aliens when you were a child. (Most Likely)

- Remembering the taste of the cake at your birthday party last week. (Unlikely)

The correct answer would be “Recalling being abducted by aliens when you were a child,” as it’s the most likely to be a false memory due to its extraordinary and improbable nature.

References

Balfour, Lyn (20 Jan. 2012) “Experience: My Baby Died in a Hot Car.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2012/jan/20/my-baby-died-in-hot-car.

Bernstein, D. M., Scoboria, A., Desjarlais, L., & Soucie, K. (2018). “False memory” is a linguistic convenience. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 5 (2), 161.

Braun, K. A., Ellis, R., & Loftus, E. F. (2002). Make my memory: How advertising can change our memories of the past. Psychology & Marketing, 19 (1), 1-23.

Diekelmann, S., Landolt, H. P., Lahl, O., Born, J., & Wagner, U. (2008). Sleep loss produces false memories. PloS one, 3 (10), e3512.

Gleaves, D. H., Smith, S. M., Butler, L. D., & Spiegel, D. (2004). False and recovered memories in the laboratory and clinic: A review of experimental and clinical evidence. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11 (1), 3-28.

Knafo, D. (2009). Freud’s memory erased. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 26 (2), 171–190.

La Ganga, Maria L. (1994-05-14). “Father Wins Suit in “False Memory” Case”. Los Angeles Times.

Lacy, J. W., & Stark, C. E. (2013). The neuroscience of memory: implications for the courtroom. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14 (9), 649-658.

Loftus, E. F. (1975). Leading questions and the eyewitness report. Cognitive psychology, 7 (4), 560-572.

Loftus, E. F., & Palmer, J. C. (1974). Reconstruction of automobile destruction: An example of the interaction between language and memory. Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 13 (5), 585-589.

McHugh, P. R (2008). Try to remember: Psychiatry’s clash over meaning, memory and mind. Dana Press.

Robinson, Dana (20 Mar. 2020). “Everything You Want to Know About OCD.” Healthline, Healthline Media, www.healthline.com/health/ocd/social-signs.

Robinson-Riegler, B., & Robinson-Riegler, G. (2016). Cognitive psychology: Applying the science of the mind. Pearson.

Saunders, J., & MacLeod, M. D. (2002). New evidence on the suggestibility of memory: The role of retrieval-induced forgetting in misinformation effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 8 (2), 127.

Schacter, D. L. (2002). The Seven Sins of Memory: How the Mind Forgets and Remembers. Houghton: Mifflin Harcourt

Weiten, W. (2010). Psychology: Themes and Variations: Themes and Variations. Cengage Learning.