Feminism generally means the belief in the social, economic, and political equality of the sexes.

Feminists share a common goal of supporting equality for men and women. Although all feminists strive for gender equality, there are various ways to approach this theory.

The history of modern feminism can be divided into four parts which are termed ‘waves.’ Each wave marks a specific cultural period in which specific feminist issues are brought to light.

This article will look into the waves of feminism throughout history until the present.

First Wave OF Feminism

How did the first wave start?

The first wave of feminism is believed to have started around 1848, often tied to the first formal Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. The convention was notably run by Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who were among the other 300 in attendance.

Stanton declared that all men and women were created equal, and thus, she advocated for women’s education, their right to own property, and organizational leadership. Many of the activists believed that their goals would be hard to accomplish without women’s right to vote. Thus, for the following 70 years, this was the main goal.

Early feminists are thought to have been inspired by feminist writings such as those by Mary Wollstonecraft’s The Vindication of the Right of Women (1792) and John Stuart Mill’s The Subjection of Women (1869). Those in the first wave were also thought to have been influenced by the collective activism of women in other reform movements such as drawing tactical insight from women participating in the French Revolution and the Abolitionist Movement.

First wave activism

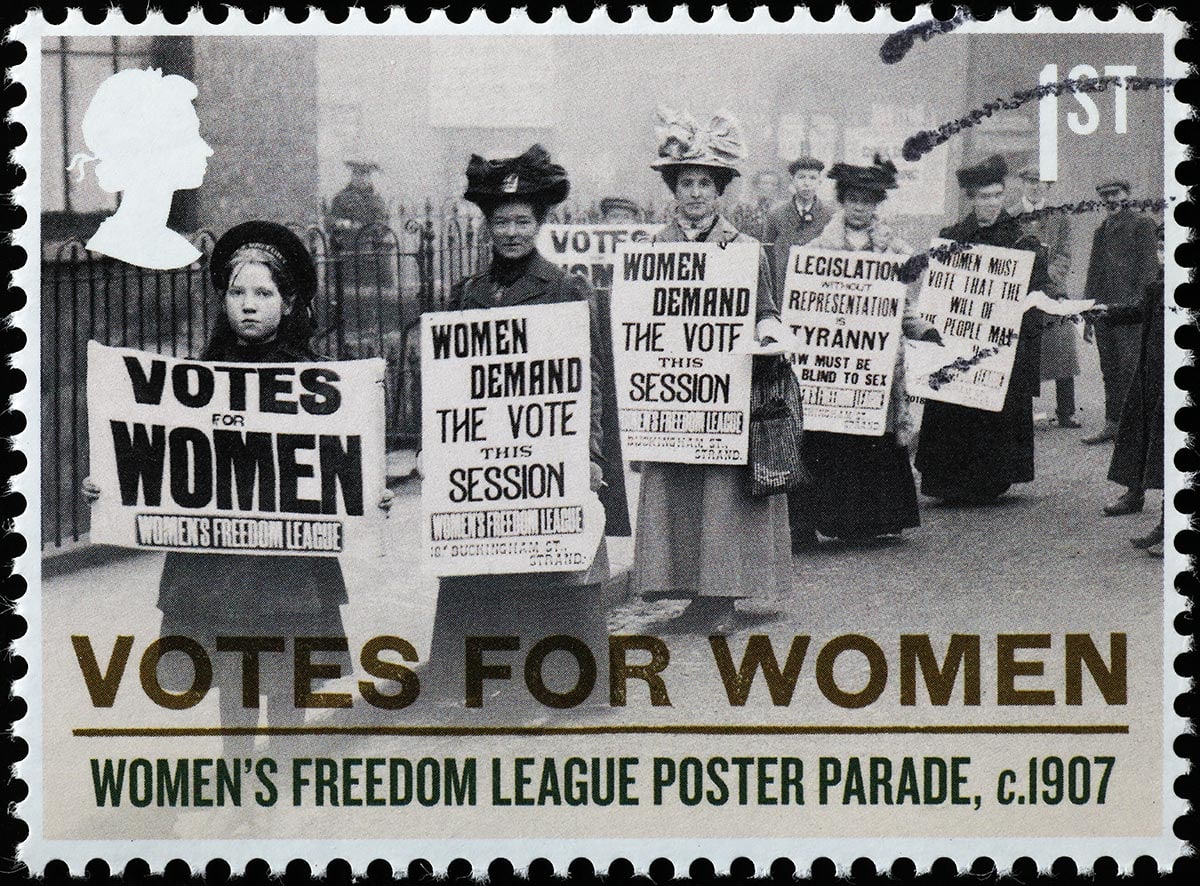

Despite its international range, the first wave of feminism was most active in the United States and Western Europe.

Activists engaged in social campaigns that expressed dissatisfaction with women’s limited rights for work, education, property, reproduction, marital status, and social agency (Malinowska, 2010).

They protested in the form of public gatherings, speeches, and writings.

The women’s suffrage movement campaigned for the right for women to vote. Their activism revolved around the press, which was the major source of information communication at the time. Early coverage of the movement was unfavorable and biased, often portraying the women as bad-looking, unfeminine, and haters of men.

In the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, suffrage was associated with a particularly prominent and militant campaign, often involving violence.

One of the most notable ‘militant’ feminists was suffragette Emily Davidson who was sent to prison several times for her activism. In 1913, she tragically died as she threw herself onto the racetrack at the Epsom Derby, causing her to be trampled by a horse. The word ‘militant’ from then on became symbolic for media depictions of suffragists’ actions.

As the movement developed, it began to turn to the question of reproductive rights for women. In 1916, Margaret Sanger opened the first birth control clinic in the United States, defying the New York state law that forbade the distribution of contraception. Sanger would later go on to establish the clinic that became Planned Parenthood.

First wave feminists had to wait until August of 1920 to be granted the right to vote. After 1920, the momentum of the movement began to dwindle after this massive success. However, other activists continued to advocate for their rights within local organizations and special interest groups.

The issue with first wave feminism

The activism of first wave feminism is often criticized for being a feminism for exclusively white women. Although the vote was granted to white women in 1920, it would take much longer for women of color to be able to exercise their right to vote.

As the suffrage movement progressed, the concerns of women of color were often overlooked by first wave feminists. For groups of women who did not fit the white, upper-class mold, the right to vote was not only tied to their gender, but also to their race and social class.

Women of color often spoke out about facing not only sexism but also racism and classism. Despite this, groups of women were often uninvited or excluded from fully participating in feminist organizations. They would often have to join segregated suffrage associations if they were included at all.

In her famous 1851 speech, ‘Ain’t I am Woman’, abolitionist Sojourner Truth described the oppression against women of color in terms of ideological inconsistency. She pointed out the exclusion of women of color from the feminist movement’s agenda.

Despite the immense work of women of color in the women’s movement, the suffrage movement eventually became one specifically for white women, often of a higher social class.

Many of the women in the movement would use racial prejudice as fuel for their work, many arguing that men of color should not be allowed to vote before white women (Davis, 1980).

Second Wave Of Feminism

How did the second wave start?

The second wave of feminism is believed to have taken place between the early 1960s to the late 1980s. This wave commenced after the postwar chaos, and it was thought to be inspired by the civil rights movement in the United States and the labor rights movement in the United Kingdom.

After achieving the vote for women, the feminist movement gradually turned its attention to women’s inequality in wider society. Many women began questioning their social roles in the workplace and in the family environment.

A noteworthy writing prior to the second wave, which may have been influential to the movement, is Simone de Beauvoir’s 1949 book titled The Second Sex. In this book, she understands women’s oppression by analyzing the particular institutions which define women’s lives, such as marriage, family, and motherhood.

Betty Friedan is thought to be one of the most famous second wave feminists. She wrote the book The Feminine Mystique in 1963 and is widely credited with kick-starting the second wave. Friedan’s book highlighted the increasing alienation and unhappiness felt by American housewives in the post-war boom years.

What are the ideas of second wave feminism?

A common principle of the second wave of feminism was women’s autonomy: an insistence on women’s right to determine what they want to do with their lives and their body. Their goals were to legalize abortions, promote easier and safer contraception, and fight racist and classist birth-control programs.

Other major issues at the time were sexual discrimination and sexual harassment, especially in the workplace and other institutional settings. Second wave feminists aimed to highlight these issues and put legislature in place to prevent this.

The second wave asked questions about the concept of gender roles and women’s sexuality. They coined the phrase ‘the personal is political’ as a means of highlighting the impact of sexism and patriarchy on every aspect of women’s private lives (Munro, 2013).

Second wave feminists were concerned with women’s lived experiences but also in media representation. As television became the main medium at this time, it was observed that women struggled for televisual presence. Data from the BBC in the late 1980s showed a disproportionate balance of 5 women to every 150 men in television-related jobs (Casey et al., 2007).

Second wave activism

Many of the second wave feminists were radical and critical in their approach. They were impatient for social and political change and brought international issues into their politics (Molyneux et al., 2021).

Many activists agreed with socialist ideas, while others were active in peace movements, revolutionary workers’ rights, and anti-racist struggles.

The practice of ‘consciousness raising’ was a popular form of activism at the time. This is where women met to discuss their experiences of sexism, discrimination, abortions, and patriarchy. This helped to create political awareness and solidarity expressed through the term ‘sisterhood’.

A significant radical feminist group during this time was the ‘New York Radical Women’ group, founded by Shulamith Firestone and Pam Allen. They wanted to spread the message that ‘sisterhood is powerful’ through their protests.

A well-known protest occurred during the Miss America Pageant in 1968. Hundreds of women marched the streets outside the event and displayed banners during the live broadcast of the event which read ‘Women’s Liberation’, which brought a great deal of public awareness to the movement.

During the second wave, the work of Black feminist groups brought the different experiences and priorities of Black feminists into focus. Writers such as bell hooks, Angela Davis, and Audre Lord paved the way for greater appreciation of the unequal power dynamics woven into early second wave feminism.

Achievements of the second wave

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 was enforced which makes it illegal for employers to have different rates of pay for women and men doing the same job. It was also the first federal law to address sex discrimination.

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act was enforced in the United States in 1974, banning discrimination in access to credit based on sex or marital status. Before then, many women could not get credit in their own name or would need to have a man’s permission to get loans or credit cards.

The Roe v. Wade case was pivotal in the legalization of abortion. In 1973, this right was granted by the United States Supreme Court meaning that women had the choice of terminating their pregnancy in the first trimester.

In addition to achieving abortion rights, second wave feminism accomplished other things such as opening up avenues for women to engage in ‘non-traditional’ educational options and jobs that would have been traditionally dominated by men.

Third Wave Of Feminism

How did the third wave start?

The third wave is thought to have spanned from the late 1980s until the 1990s. There are some overlaps and continuations from second wave feminism, but many third wave feminists simply sought to rid the perceived rigid ideology of second wave feminists.

The young feminists of this era were often the children of second wave feminists. They were growing up in a world of mass media and technology, and they saw themselves as more media savvy than the feminists from their mothers’ generation.

Feminist writer Rebecca Walker explained that it seemed that to be a feminist before this time, was to conform to an identity and way of living that does not allow for individuality. That can lead people to pit against each other; female against male, black against white, etc. (Snyder, 2008).

Third wave feminists are believed to be less rigid and judgmental compared to second wavers who are suggested to be sexually judgmental, anti-sexual, and see having too much fun as a threat to the revolution (Wolf, 2006).

Third wave feminism is believed to be shaped by postmodern theory. Feminists of the time sought to challenge, reclaim, and redefine ideas of the self, the fluidity of gender, sexual identity, and what it means to be a woman.

One of the defining moments of the third wave was when allegations were made against Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas. Anita Hill, who was a co-worker claimed that Thomas had sexually harassed her years prior. This led to a widely publicized case against Thomas which gained huge media attention.

The ideas of third wave feminism

Third wave feminists depict their feminism as more inclusive and racially diverse than previous waves.

Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality to describe how everyone has their own unique experiences of discrimination and oppression. For instance, a black woman can be oppressed on the basis of being a woman, but also for being black.

The introduction of intersectionality by Crenshaw in 1989 may have helped shape third wave feminists’ perception of how each woman has a different identity.

Not only differences based on race, ethnicity, or social class, but also for identities such as women who partake in sport, beauty, music, and religion – those which may have clashed with previous ideas about feminism in the past.

Since third wavers question the gender binary male/female and have a generally non-essentialist approach to considering gender, transgender individuals fit better into this wave than in second wave thinking (Snyder, 2008).

Third wave feminism ideals are focused on choice. Whatever a woman chooses to do, it is feminist as long as she made that choice. They claim that using makeup is not a sign that a woman is adhering to the ‘male gaze’, instead, a woman can use makeup for themselves without any loaded issues.

Third wavers feel entitled to interact with men as equals and actively play with femininity. The concept of ‘girl power’ also came about at this time.

Third wave feminism is often pro-sex, defending pornography, sex work, intercourse, and marriage, and reducing the stigma surrounding sexual pleasure in feminism. This contrasts with a lot of the radical feminists of the second wave who would often reject femininity and disengage from heterosexual intercourse with men.

Many third wave literature emphasizes the importance of cultural production, focusing on female pop icons, hip-hop music, and beauty culture, rather than on traditional politics.

Riot Grrrl was regarded both as a movement and a music genre in the early 1990s. It began in Olympia, Washington where a group of women met to discuss the sexism in the punk scene.

Being enraged by this, they sought to establish their own space to produce punk music that stood for female empowerment and created an environment where women could exist without the male gaze.

Third wavers faced a lot of criticism. The sexualized behavior of feminists was questioned as to whether this truly represented sexual liberation and gender equality or whether it was old oppressions in disguise.

Likewise, many claimed the movement lived past its usefulness and that the wave did not contribute to anything of substance. There was nothing revolutionary that happened during this wave like there was with the right to vote being granted to women in the first wave, and legislative changes made during the second wave.

Nevertheless, it can be argued that the third wave encouraged a new generation of feminists, and it was a step that paved the way for future waves to come.

Fourth Wave Of Feminism

How did the fourth wave start?

While there is some disagreement, it is generally accepted that there is a fourth wave of feminism which may have started anywhere from 2007 to 2012 (Sternadori, 2019) and continues to the present day.

Prudence Chamberlain (2017) defines the fourth wave by its focus on justice for women, particularly those who have experienced sexual violence. The current wave combines aspects of the previous waves though with an increased focus on intersectionality and sub-narratives such as transgender activism.

Many claim that the internet itself and increased social media usage has enabled a shift from third wave to fourth wave feminism (Munro, 2013). Chamberlain notes that ‘feminists who identify as second or third wave are still participating in and driving activism’.

She claims generations have joined forces as ‘social media is providing a platform to a wide range of women who are able to use the connectivity and immediacy’.

The internet has become a platform for feminists from around the world to come together to ‘call out’ cultures in which sexism and misogyny can be challenged and exposed. This is continuing the influence of the third wave, with a focus on micropolitics, challenging sexism in adverts, film, literature, and the media, among others.

Facebook was forced to confront the issue of hate speech on its website after initially suggesting that images of women being abused did not violate its terms of service (Munro, 2013).

In the United Kingdom, campaigns such as ‘No More Page 3’ (a reference to The Sun’s page 3, which from 1970 to 2015 featured a topless model) and The Everyday Sexism Project were some of the earlier online campaigns in the fourth wave.

After the inauguration of Donald Trump as president of the United States in 2017, a Women’s March was held which captured the international spotlight as arguably the largest and most peaceful single-day protest in US history.

In the same year, the #MeToo movement hit social media in over 85 countries, where individuals shared their experiences of sexual abuse and harassment to demonstrate the widespread number of cases of sexual violence and to create solidarity among victims.

This allowed people to see that sexual violence is not a personal problem but a structural issue (Sternadori, 2019).

The fourth wave encourages women to be politically active and passionate about the previous wave’s issues, such as the wage gap and ending sexual violence.

The main goals of the fourth wave are thought to call out social injustices and those responsible for them, as well as to educate others on feminist issues and to be inclusive to all groups of women.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is a wave metaphor used to describe the feminist movement?

The wave metaphor of feminism is believed to have been coined in 1968 when Martha Weinman Lear published an article in the New York Times called ‘The Second Wave Feminist Wave’.

The article connected the suffrage movement of the 19th and early 20th centuries with the women’s movements during the 1960s. This new terminology quickly spread and became the popular way to define feminism.

The wave metaphor suggests that feminist activism is unified around one set of ideas that comes and goes like waves hitting the shore. This idea suggests that activism peaks at certain times and recedes at others (Nicholson, 2010).

What is a criticism of the wave metaphor?

The wave metaphor is thought to be reductive since it suggests that each wave of feminism peaks with a single unified agenda, when in fact the feminist movement has a history of different ideas, goals, and activism.

With a wave metaphor, there is also the general understanding that waves crash after one another – the newest wave is thought to replace or in some way, obliterate the previous waves. However, this diminishes the achievements of previous feminist movements.

Are the waves of feminism universal?

A key thing to point out when considering the waves of feminism is that they mostly only apply to Western countries.

The activism of the suffragettes and of those in second wave feminism especially was focused primarily on the United States and Western Europe. As such, the waves of feminism cannot be applied universally.

References

Calvert, B., Casey, N., Casey, B., French, L., & Lewis, J. (2007). Television studies: The key concepts. Routledge.

Chamberlain, P. (2017). The feminist fourth wave: Affective temporality. Springer.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In Feminist Legal Theories (pp. 23-51). Routledge.

Ford, D. R. (2021). Review of Prudence Chamberlain (2017). The Feminist Fourth Wave: Affective Temporality. Postdigital Science and Education, 3 (2), 631-633.

Malinowska, A. (2020). Waves of Feminism. The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication, 1, 1-7.

Molyneux, M., Dey, A., Gatto, M. A., & Rowden, H. (2021). New Feminist Activism, Waves and Generations (No. 40). UN Women Discussion Paper.

Munro, E. (2013). Feminism: A fourth wave?. Political insight, 4 (2), 22-25.

Nicholson, L. (2010). Feminism in ‘Waves’: Useful Metaphor or Not?. New Politics, 12 (4), 34-39.

Snyder, R. C. (2008). What is third-wave feminism? A new directions essay. Signs: Journal of women in culture and society, 34 (1), 175-196.

Sternadori, M. (2019). Situating the Fourth Wave of feminism in popular media discourses . Misogyny and Media in the Age of Trump, 31-55.

Wolf, N. (2006). ‘Two Traditions,’from Fire with Fire. The Women’s Movement Today: An Encyclopedia of Third-Wave Feminism (2006), 13-19.