In contrast to the structural perspective, the functional perspective of attitudes focuses on how attitudes can serve a purpose for the individuals who possess them.

In general, the functional view suggests that attitudes play a role in bridging the gap between a person’s internal needs (such as safety and self-expression) and the external environment, which comprises other people and information.

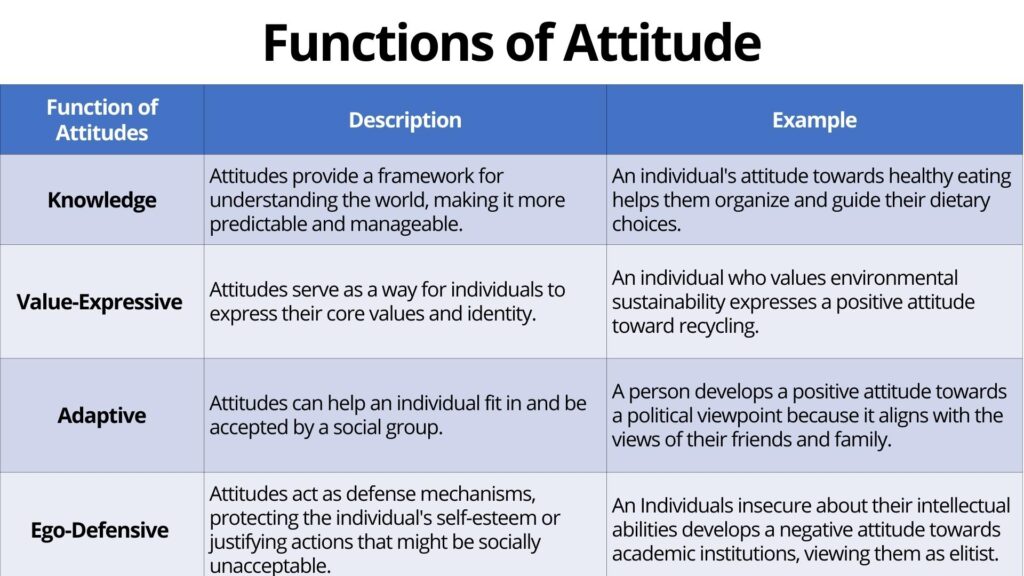

Therefore, each attitude held by an individual is expected to assist them in fulfilling their needs in some way. Katz (1960) proposed that the needs satisfied by attitudes, and consequently the functions they serve, can be classified into four main categories:

| Function | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Attitudes provide a framework for understanding the world, making it more predictable and manageable. | An individual’s attitude towards healthy eating helps them organize and guide their dietary choices. |

| Value-Expressive | Attitudes serve as a way for individuals to express their core values and identity. | An individual who values environmental sustainability expresses a positive attitude toward recycling. |

| Adaptive | Attitudes can help an individual fit in and be accepted by a social group. | A person develops a positive attitude towards a political viewpoint because it aligns with the views of their friends and family. |

| Ego-Defensive | Attitudes act as defense mechanisms, protecting the individual’s self-esteem or justifying actions that might be socially unacceptable. | An individual insecure about their intellectual abilities develops a negative attitude towards academic institutions, viewing them as elitist. |

Knowledge Function

According to Daniel Katz’s theory (1960), attitudes serve a knowledge function by organizing and categorizing information in our cognitive system.

Attitudes act as schemas or mental structures that help us make sense of the world around us. They provide a framework for organizing our thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions, facilitating the processing and storage of information.

The knowledge function of attitudes refers to the need for maintaining an organized, stable, and meaningful structure of the world. This function aids in making the world more predictable and manageable. When people form attitudes, they often do so to make sense of their environment and to understand the world around them.

For example, if a person holds an attitude that eating healthy is important, it helps them organize their behaviors and decisions related to food and health. They will more likely choose to eat fruits and vegetables over junk food, or prefer to go for a run instead of watching television.

In a broader sense, attitudes that serve the knowledge function can also contribute to a sense of self and identity. For instance, if someone identifies as an environmentalist, their attitudes towards recycling, renewable energy, and conservation help define that identity and provide a consistent way to interpret information related to these topics.

This knowledge function of attitudes is vital because it reduces uncertainty and provides predictability in our lives. It also shapes our perceptions and guides our responses to various situations and people, thereby influencing our social interactions and personal decisions.

Value Expressive Function

The value expressive function refers to the role attitudes play in expressing an individual’s self-concept and core values. These attitudes reflect the individual’s self-identity and are a means through which they can communicate their values and beliefs to others.

In essence, attitudes serve as a way for people to define themselves, to express who they are, and what they stand for.

For example, a person who values environmental sustainability might hold and express a positive attitude toward recycling. This attitude is an outward reflection of their internal values and helps them communicate to others what is important to them.

The value-expressive function of attitudes is particularly salient when it comes to publicly expressed attitudes on societal issues. For instance, one’s attitude towards social justice issues, like gender equality or racial equality, often serves the value-expressive function by articulating one’s core values and beliefs to others.

Furthermore, attitudes that serve the value-expressive function can also bring a sense of self-consistency and integrity, as they help align one’s outward behaviors and expressions with their inner beliefs and values. It’s part of the larger psychological need for self-affirmation and maintaining a positive self-image.

The attitudes we express (1) help communicate who we are and (2) may make us feel good because we have asserted our identity. Self-expression of attitudes can be non-verbal, too: think bumper sticker, cap, or T-shirt slogan.

Therefore, our attitudes are part of our identity and help us be aware through expressing our feelings, beliefs, and values.

Adaptive Function

The adaptive function posits that people hold certain attitudes because they are beneficial or rewarding to them in their social environment.

Essentially, the adaptive function of attitudes involves forming opinions that align with those of groups that are important to the individual in order to gain acceptance or approval, or to avoid social discomfort or disapproval.

If a person holds and/or expresses socially acceptable attitudes, others will reward them with approval and social acceptance.

For example, when people flatter their bosses or instructors (and believe it) or keep silent if they think an attitude is unpopular. Again, expression can be nonverbal [think politician kissing baby].

The adaptive function can be particularly influential in situations where social pressures are high or when the opinion of the group or society carries significant weight. It underscores the powerful role of social influence and conformity in shaping our attitudes.

The adaptive function of attitudes is inherently linked to the behavioral component of attitudes.

Attitudes, then, are to do with being a part of a social group, and the adaptive functions help us fit in with a social group. People seek out others who share their attitudes and develop similar attitudes to those they like.

It’s important to note, however, that attitudes serving the adaptive function may not always align with an individual’s personal beliefs or values, which can sometimes lead to internal conflict.

Ego-defensive

The ego-defensive function suggests that certain attitudes are held because they help protect an individual’s self-esteem or justify actions that might otherwise be considered socially unacceptable.

Essentially, these attitudes serve as defense mechanisms, protecting the individual from acknowledging certain facts about themselves or the world around them that they find difficult or uncomfortable to admit.

The ego-defensive function refers to attitudes that protect our self-esteem or justify actions that make us feel guilty.

For example, an individual who is insecure about their intellectual abilities may develop a negative attitude toward academic institutions, viewing them as elitist and irrelevant. This attitude could serve to defend their ego by providing a socially acceptable reason for their perceived failures or challenges in an academic context.

Similarly, someone may hold biased or prejudiced attitudes toward a certain group as a way of boosting their own self-esteem or their in-group status. This type of attitude serves the ego-defensive function by providing a scapegoat or an “other” to blame, which can help the individual avoid confronting their own insecurities or shortcomings.

The basic idea behind the functional approach is that attitudes help people mediate between their inner needs (expression, defense) and the outside world (adaptive and knowledge).

However, while these attitudes can serve to protect an individual’s self-esteem in the short term, they can also lead to harmful stereotypes and biases in the long term.

References

Eagly, A. H. Chaiken. S.(1998). Attitude, structure and function. Handbook of social psychology, 269-322.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Hogg, M., & Vaughan, G. (2005). Social Psychology (4th edition). London: Prentice-Hall.

Katz, D. (1960). Public opinion quarterly, 24, 163 – 204.

LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. Actions. Social Forces, 13, 230-237.