Gender coding is used when assigning specific traits or behaviors primarily or exclusively to certain genders. Gender codes are often presented by words and phrases associated with a particular gender, specifically male or female.

These words and phrases reflect a culture’s ideas about gender and are often based on stereotypes.

Examples of typically ‘masculine-coded’ words that might be used include terms such as competitive, dominate, driven, and challenge. Examples of typically ‘feminine-coded’ words include loyal, collaborative, understanding, and encouraging.

Where Is Gender Coding Used?

Gender codes often appear in job advertisements where employers will use adjectives that describe personal attributes they are seeking from an employee (e.g., motivation and drive) rather than other factual information such as experience and qualifications.

A study found many male-coded words (e.g., dominant and competitive) within finance internship advertisements, which are essential to building careers in finance. They found that female applicants are less likely to consider their suitability for roles that use male-coded language (Oldford & Fiset, 2021).

Job advertisements for emergency medicine physicians tend to contain more masculine-coded language, with nearly all job advertisements for this position in a study containing at least one gender-coded word (O’Brien et al., 2022).

Further to gender-coded job advertisements, the jobs themselves may also be gender-coded (Grip & Jansson, 2022). Occupations, positions, and work tasks are often gendered, meaning they are assumed to be more suited for particular genders (Acker, 1990). It can be assumed that the labor market is part of the influence behind creating and recreating gendered identities (McDowell, 2004).

According to one study, job performance evaluations are also thought to include gender codes (Correll et al., 2020). The researchers determined that when communal terms were used in evaluations, 61% of the time, these applied to women.

Aside from jobs, gender coding can be seen in other areas, such as when it comes to categorizing actions. Gender influences how professionals view violence, with physical violence considered masculine and relational violence as feminine.

Boys are often described as less violent when they are involved in relational violence, while physical violence among girls is not always taken seriously (Lunneblad & Johansson, 2021).

What Is The Purpose Of Gender Coding?

While gender codes may not always be intentional, they can give subtle messages regarding what is acceptable for males and females.

For example, with the example of gender-coded violence, boys and men may be excused when they portray relational types of violence. In comparison, girls and women may learn it is less acceptable for them to display similar types of violence.

Although any gender can exhibit characteristics that are typically masculine or feminine-coded, they can still be used to serve a purpose in job advertisements. Much masculine-coded language in a job advertisement can convey that mostly men work at the company and that other genders are not welcome there.

The same can be true for men considering jobs with feminine-coded language in the job advertisement. Using gender coding can thus make specific jobs unappealing to certain genders, whether this is the true intention of employers or not.

What Is The Impact Of Gender Coding?

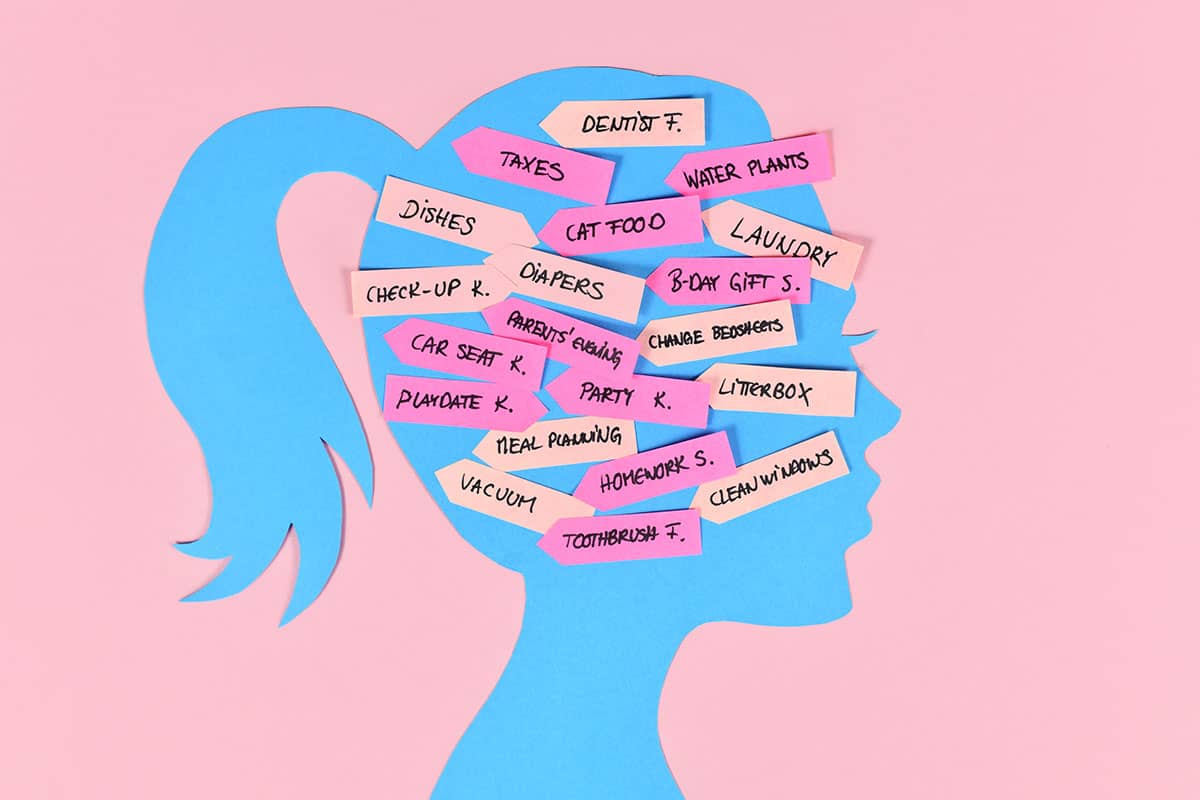

The impact of gender coding is that stereotypical ideas of what genders are like persist, even if they are not necessarily true.

In many countries, including seemingly progressive ones, men are still perceived as more agentic, while women are viewed as more communal (Oldford & Fiset, 2021).

To be agentic means to be confident and decisive, which are typically ascribed to masculine qualities. To be communal, on the other hand, is to be warm and supportive, words that are typically ascribed to more feminine attributes.

Due to gender coding, women may not feel as comfortable applying for jobs that appear to be searching for male candidates and instead will apply for positions that include terms such as ‘interpersonal’ and ‘caring.’ Both men and women may lose out on career opportunities if they feel that the language used in job descriptions does not apply to their gender.

Likewise, if mostly women are applying to jobs that use feminine-coded language, and mostly men are applying to jobs that use masculine-coded language, workplaces can remain or become segregated (Grip & Jansson, 2022).

Using communal and feminine-coded wording may not translate into favorable rewards in the workplace. According to one study, women were not given higher ratings when these types of words were used in performance evaluations, even if the descriptions were positive (Correll et al., 2020).

Women were praised for being helpful, but being helpful was not highly valued in the workplace. Instead, those described as ‘taking charge’ were viewed favorably.

Due to this, women’s chances of increased pay and higher positions were argued to have been affected by gendered attitudes expressed in gender codes (Correll et al., 2020).

How To Avoid Gender Codes In A Job Description

To avoid using gender codes in job descriptions and advertisements, using non-gendered language encourages people of all genders to apply for jobs. This is also a way of providing greater opportunities for a diverse and inclusive workplace.

Likewise, avoiding the use of gendered language or including a balance of these terms can help to ensure that workplaces are not subtly predicting the gender of the person they are going to hire.

Using superlatives such as ‘superior’ and ‘expert’ in job descriptions may discourage women from applying, who are typically more collaborative than competitive than men. Moreover, using gender-neutral job titles in job descriptions can help to attract people of every gender to apply.

References

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4 (2), 139-158.

Correll, S. J., Weisshaar, K. R., Wynn, A. T., & Wehner, J. D. (2020). Inside the black box of organizational life: The gendered language of performance assessment. American Sociological Review, 85 (6), 1022-1050.

Grip, L., & Jansson, U. (2022). ‘The right man in the right place’–the consequences of gender-coding of place and occupation in collaboration processes. European Journal of Women”s Studies, 29 (2), 250-265.

Lunneblad, J., & Johansson, T. (2021). Violence and gender thresholds: A study of the gender coding of violent behavior in schools. Gender and Education, 33 (1), 1-16.

McDowell, L. (2004). Thinking through work: Gender, power, and space. Reading economic geography, 315-328.

O”Brien, K., Petra, V., Lal, D., Kwai, K., McDonald, M., Wallace, J., Jeanmonod, C. & Jeanmonod, R. (2022). Gender coding in job advertisements for academic, non-academic, and leadership positions in emergency medicine. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 55, 6-10.

Oldford, E., & Fiset, J. (2021). Decoding bias: Gendered language in finance internship job postings. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 31, 100544.