Take-home Messages

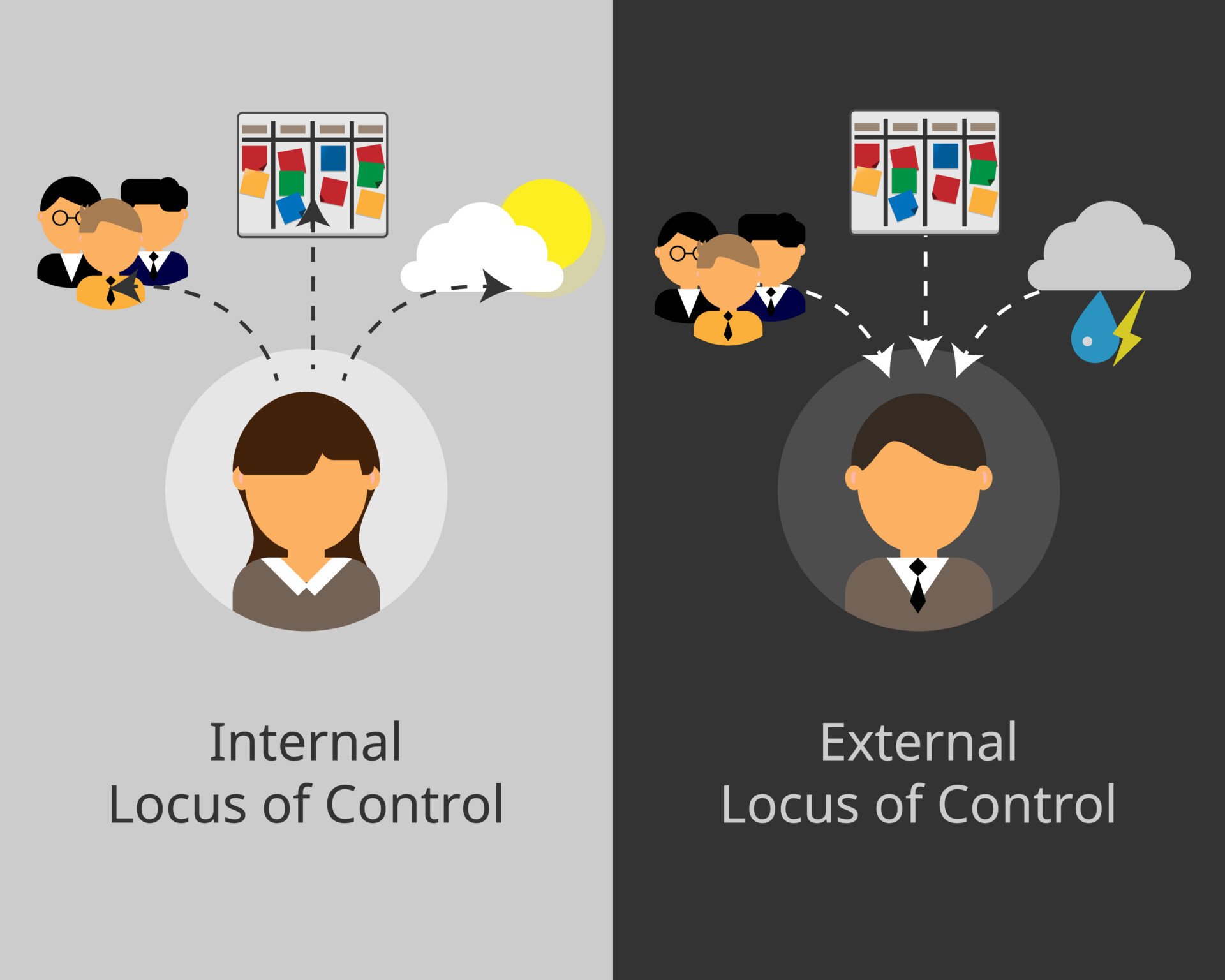

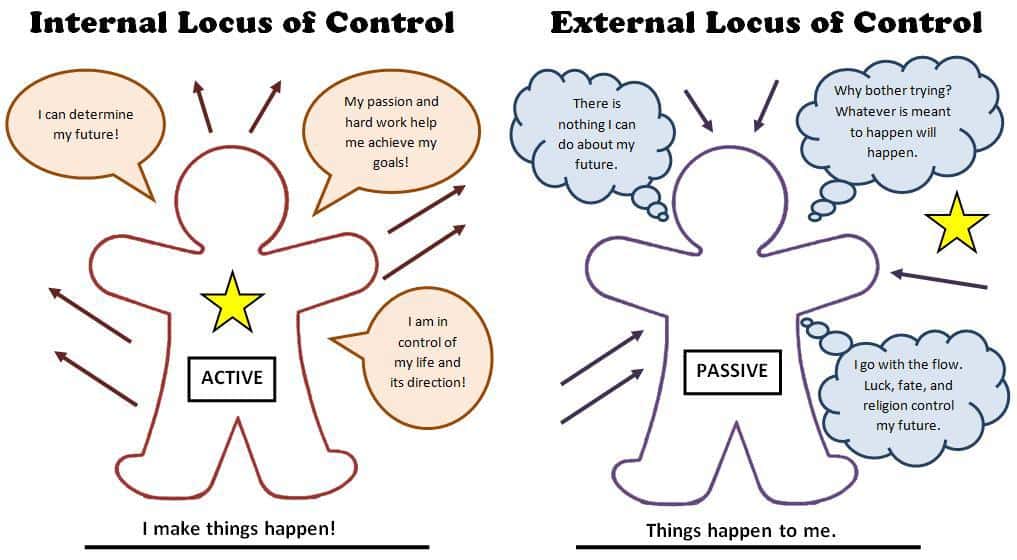

- The term ‘Locus of control’ refers to how much control a person feels they have in their own behavior. A person can either have an internal or external locus of control (Rotter, 1954).

- People with a high internal locus of control perceive themselves as having much personal control over their behavior and are, therefore, more likely to take responsibility for their behavior. For example, I did well on the exams because I revised extremely hard.

- In contrast, a person with a high external locus of control perceives their behaviors as a result of external influences or luck – e.g., I did well on the test because it was easy.

- Research has shown that people with an internal locus of control tend to be less conforming and obedient (i.e., more independent). Rotter proposes that people with an internal locus of control are better at resisting social pressure to conform or obey, perhaps because they feel responsible for their actions.

- Locus of control is an important term to know in almost every branch of the psychology community. This is mainly because it can be applied in many aspects of daily life; whether the locus is external or internal, it will – by definition – affect your mind, body, and even actions.

- Fields like educational psychology, clinical psychology, and even health psychology have all made strides in researching the phenomenon to understand more about how one can control or improve one’s locus of control.

- Experts in the field of psychology often disagree with each other regarding whether differences should be attributed based on cultural differences or whether a more worldwide measure of locus of control will be more helpful when it comes to practical application.

Internal vs. External Locus of Control

Locus of control is how much individuals perceive that they themselves have control over their own actions as opposed to events in life occurring instead because of external forces. It is measured along a dimension of “high internal” to “high external”.

A high internal perceive themselves as having a great deal of personal control and therefore are more inclined to take personal responsibility for their behavior, which they see are being a product of their own effect. High external perceive their behavior as being caused more by external forces or luck.

It is also worth mentioning that the term locus of control is not to be confused with attributional style. Locus of control refers to an idea connected with anticipations about the future, while attributional style is a concept that is instead concerned with finding explanations for past outcomes.

Example

People with an internal locus of control accept occasions in their day-to-day existence as controllable. To be more specific, this means that they can recognize instances where destiny is controllable: for instance, an individual is taking a test for a driver’s license.

A person with an internal locus of control will attribute whether they pass or fail the exam due to their own capabilities. This individual would praise their own abilities if they passed the test and would also recognize the need to improve their own driving if they had instead failed the exam.

An individual with an external locus of control would perceive the same event differently. This individual would be more likely to blame other factors such as the weather, their current condition, or even the exam itself as an excuse rather than accept that the exam went the way it did because of personal decisions.

Rather than accept that part of the blame rests on them, the event is instead attributed to occur because of uncontrollable forces (destiny/fate/etc.).

Locus of control is one of the four elements of center self-assessments – one’s principal examination of oneself – alongside neuroticism, self-viability, and self-esteem.

The idea of center self-assessments was first inspected by Judge, Locke, and Durham (1997), and since has demonstrated to foresee a few work results, explicitly, work fulfillment and occupation performance.

In a subsequent report, Judge et al. (2002) contended that locus of control, neuroticism, self-viability, and confidence elements might all influence each other.

How it Works

The first recorded trace of the term Locus of Control comes from Julian B. Rotter’s work (1954) based on the social learning theory of personality. It is a great example of a generalized expectancy related to problem-solving, a strategy that applies to a wide variety of situations.

In 1966 Rotter distributed an article in Psychological Monographs that summed up around a decade of extensive research (by Rotter and his understudies), with most of this work actually never being published beforehand.

It is speculated that Locus of Control may have come beforehand as a term coined by a psychologist by the name of Alfred Adler. The evidence for this is lacking, however, so the main bulk of the credit for the concept lies in Rotter and his understudies” early works.

One of these understudies was William H. James. This psychologist would later go on to produce his own work in the field, but while he was under the tutelage of Rotter, he wanted to study what he denoted as “expectancy shifts.”

These “expectancy shifts” can be classified as follows:

Typical Expectancy Shifts

Typical expectancy shifts derive from the belief that success (or failure) will be the determining notion for whatever activity/action is preceded next (that is to say, if one succeeds at something, then the expectancy is that they will succeed again).

Let’s say – for example – that during a basketball game, a player shoots a basketball and scores a point. After attempting this three times and scoring all three, the player might come to believe that (due to the fact the player has been continuously successful) if they continue to shoot, they will continue to score.

Atypical Expectancy Shifts

Atypical expectancy shifts, which derive from the belief that success (or a failure) will not have any determining notion for whichever activity/action that follows it (that is to say, if one succeeds at an activity, then the expectancy for the subsequent one is independent of this result; one could fail or succeed).

To give an example of this, picture someone who is at a casino. This individual places a bet on the ball, landing on a red number in the roulette wheel.

After three spins of the wheel, the ball has landed once in a red number, once in a black number, and finally once in a green number. The individual will (hopefully) most likely come to the conclusion that the result of the spin is independent of the last result, with each individual spin being a stand-alone event.

Additional research supported the hypothesis that typical expectancy shifts were much more common amongst individuals who had confidence in their own abilities, whilst those who didn’t really believe in their capabilities tended to attribute their expectancies toward fate rather than skill.

In other words, the distinction lies in whether the cause is internal or external; those who have faith in their own abilities will look towards an internal cause and adapt a typical expectancy shift, while those who attribute their results to external causes will most likely exhibit an atypical expectancy shift.

Rotter has made strides in this area of his research, covering this phenomenon in multiple works (1975). He has talked about issues and confusion in others’ utilization of the interior versus outer build, explaining how misconceptions and miscommunication have led people to mistake Locus of Control for other psychological terms.

Measurement

There are multiple ways to measure locus of control, but by far, the most widely used questionnaire is the 13-item (plus six filler items) forced-choice scale of Rotter (1966). This questionnaire first came into the scene in 1966 and is arguably still the best way to determine the locus of control in the present day. This does not mean that this is the only popular questionnaire.

Another example is Bialer’s (1961) 23-item scale for children, which actually even predates Rotter’s work. Other examples would be the Crandall Intellectual Ascription of Responsibility Scale (Crandall, 1965) and the Nowicki-Strickland Scale (Nowicki & Strickland, 1973), though again, most of these are not used in favor of Rotter’s 1966 questionnaire.

One of his understudies (again, William H. James) was actually responsible for developing one of the earliest psychometric scales to assess locus of control for his unpublished doctoral dissertation, supervised by Rotter at Ohio State University. As just mentioned, however, the work remains unpublished yet it is an example of just how much influence Rotter and his students have over the origins of the term.

Many measures of locus of control have appeared since Rotter’s scale. These vary from the original that predate Rotter’s own original designs to the locus of controls designed specifically for groups – like children (such as the Stanford Preschool Internal-External Scale for three- to six-year-olds).

According to the data analyzed by Furnham and Steele (1993), they suggest that the most reliable, valid questionnaire for adults is The Duttweiler (1984) Internal Control Index (ICI), which might be the better scale. Right off the bat, an advantage these scales have is that they address perceived problems with the Rotter scales.

These issues include adjusting the forced-choice format, removing the susceptibility to social desirability and heterogeneity (as indicated by factor analysis), and the natural improvements that come from developing something almost 30 years after the Rotter scales.

One important thing to note is that while other scales existed in 1984 besides the Duttweiler scales to measure locus of control, they all appear to fall victim to the same problems that the Rotter scales never originally addressed.

The primary difference lies in the removal of the forced-choice format used in Rotter’s scale. Previously, individuals had to affirm whether the assertion presented by the scale was true or false.

However, with Duttweiler’s 28-item ICI, which utilizes a Likert-type scale, individuals must specify whether they would behave as described in each of the 28 statements rarely, occasionally, sometimes, frequently, or usually.

This approach makes the scale much more adaptable to human nature’s nuances than the original Rotter scales.

The ICI gives individuals much more choice by assessing variables pertinent to internal locus. These include but are not limited to cognitive processing, resistance to social influence, self-reliance, autonomy, and delay of gratification. Small validation studies have indicated that the scale had good internal consistency reliability (a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85)

Applications

The field most associated with locus of control is health psychology, mainly because the original scales to measure locus of control originated in the health domain of psychology.

These first scales were originally reviewed and approved by Furnham and Steele in 1993; they have since remained an essential part of health and other branches of psychology.

Out of the reviewed scales, The best-known in the field of health psychology are the Health Locus of Control Scale and the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale, or MHLC (Wallston & Wallston, 2004).

The idea that health psychology and Locus of control go together is based on the concept that health may be attributed to three sources: internal factors (such as self-determination of a healthy lifestyle), powerful external factors (the words of a doctor or a loved one) or luck/destiny/coincidence.

Those that belong to the last group are almost impossible to deal with, given that they have a firm belief that nothing they will do can either change or avert what is going to happen either way.

The scales reviewed by Furnham and Steele (1993) have directly contributed to multiple areas of health psychology. Take, for example, Saltzer’s (1982) Weight Locus of Control Scale or Stotland and Zuroff’s (1990) Dieting Beliefs Scale.

Both these scales tackled the issue of obesity and shed light on how it affects different types of individuals. These scales do not limit themselves only to the physical aspects of individuals; take, for example, Wood and Letak’s (1982) Mental health locus of control scale.

These scales try to measure the stages of health and depression that an individual is currently in; there’s even a scale meant for measuring cancer and cancer-like symptoms (the Cancer Locus of Control Scale of Pruyn et al., 1990).

Perhaps the most important link that locus of control has to health psychology is Claire Bradley’s work, which links locus of control to the management of diabetes mellitus. This empirical data was reviewed by Norman and Bennet (1997) and they note that the data collected on whether certain health-related behaviors are related to internal health locus of control is, at best ambiguous.

For example, they point out that according to certain studies, locus of control was found to be linked with increased exercise, but also note how other studies have mentioned that the impact that exercise has on locus of control is either minimal or non-existent.

Activities such as jogging or running have long since been dismissed as lone factors for influencing any sort of command in one’s locus of control.

This ambiguity goes on in the study, with data on the relationship between internal health locus of control and other health-related behaviors also being suspicious.

These health-related behaviors include breast self-examination, weight control, and preventive-health behavior and in the study, it is said that alcohol consumption has a direct relationship with one’s internal locus of control.

Again with alcoholism as a factor, the same problems occur; the facts from the study begin to contradict themselves. During their analysis of the validity of the study, Norman and Bennett (1998) realized that some of the studies concluded by suggesting that a link existed between alcoholism and having an increased externality for health locus of control.

This goes against what is known right now, which is that – according to multiple other studies – alcoholism is related instead to increased internality in regards to an individual’s locus of control. The perceived notion is that alcoholism is directly related to the strength of the locus, not to what type of locus exists.

That is to say, it does not matter whether an individual has an internal or external locus of control; alcohol consumption is only related to the actual strength of that respective locus of control.

FAQs

What is internal locus of control?

An internal locus of control refers to the belief that one can control their own life and the outcomes of events. Individuals with a high internal locus of control perceive their actions as directly influencing the results they experience.

What is external locus of control?

An external locus of control refers to the belief that external factors, such as fate, luck, or other people, are responsible for the outcomes of events in one’s life rather than one’s own actions.

Who proposed the locus of control concept?

The concept of locus of control was proposed by psychologist Julian B. Rotter in 1954.

References

Bennett, P., Norman, P., Murphy, S., Moore, L., & Tudor-Smith, C. (1998). Beliefs about alcohol, health locus of control, value for health and reported consumption in a representative population sample. Health Education Research, 13 (1), 25-32.

Bialer, I. (1961). Conceptualization of success and failure in mentally retarded and normal children. Journal of personality.

CRANDALL, V. C., KATKOVSKY, W., & CRANDALL, V. J. (1965) Children’s beliefs in their own control of reinforcements in intellectual-academic achievement situations. Child Development, 36, 91-109.

Duttweiler, P. C. (1984). The internal control index: A newly developed measure of locus of control. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 44 (2), 209-221.

Furnham, A., & Steele, H. (1993). Measuring locus of control: A critique of general, children’s, health‐and work‐related locus of control questionnaires. British Journal of Psychology, 84 (4), 443-479.

Nowicki, S., & Strickland, B. R. (1973). A locus of control scale for children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 40 (1), 148.

Norman, P., Bennett, P., Smith, C., & Murphy, S. (1997). Health locus of control and leisure-time exercise. Personality and Individual Differences, 23 (5), 769-774.

Norman, P., Bennett, P., Smith, C., & Murphy, S. (1998). Health locus of control and health behavior. Journal of Health Psychology, 3 (2), 171-180.

Rotter, J. B. (1954). Social learning and clinical psychology.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 80 (1), 1.

Rotter, J. B. (1975). Some problems and misconceptions related to the construct of internal versus external control of reinforcement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43 (1), 56.

Saltzer, E. B. (1982). The weight locus of control (WLOC) scale: a specific measure for obesity research. Journal of Personality Assessment, 46 (6), 620-628.

Stotland, S., & Zuroff, D. C. (1990). A new measure of weight locus of control: The Dieting Beliefs Scale. Journal of personality assessment, 54 (1-2), 191-203.

Wallston, K. A., Strudler Wallston, B., & DeVellis, R. (1978). Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health education monographs, 6 (1), 160-170.

Wallston, K. A., & Wallston, B. S. (2004). Multidimensional health locus of control scale. Encyclopedia of health psychology, 171, 172.

Watson, M., Greer, S., Pruyn, J., & Van Den Borne, B. (1990). Locus of control and adjustment to cancer.

Psychological Reports, 66

(1), 39-48.

Wood, W. D., & Letak, J. K. (1982). A mental-health locus of control scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 3 (1), 84-87.

Keep Learning

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological monographs: General and applied, 80(1), 1.

- Rotter, J. B. (1990). Internal versus external control of reinforcement: A case history of a variable. American psychologist, 45(4), 489.

- Stotland, S., & Zuroff, D. C. (1990). A new measure of weight locus of control: The Dieting Beliefs Scale. Journal of personality assessment, 54(1-2), 191-203.

- Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior