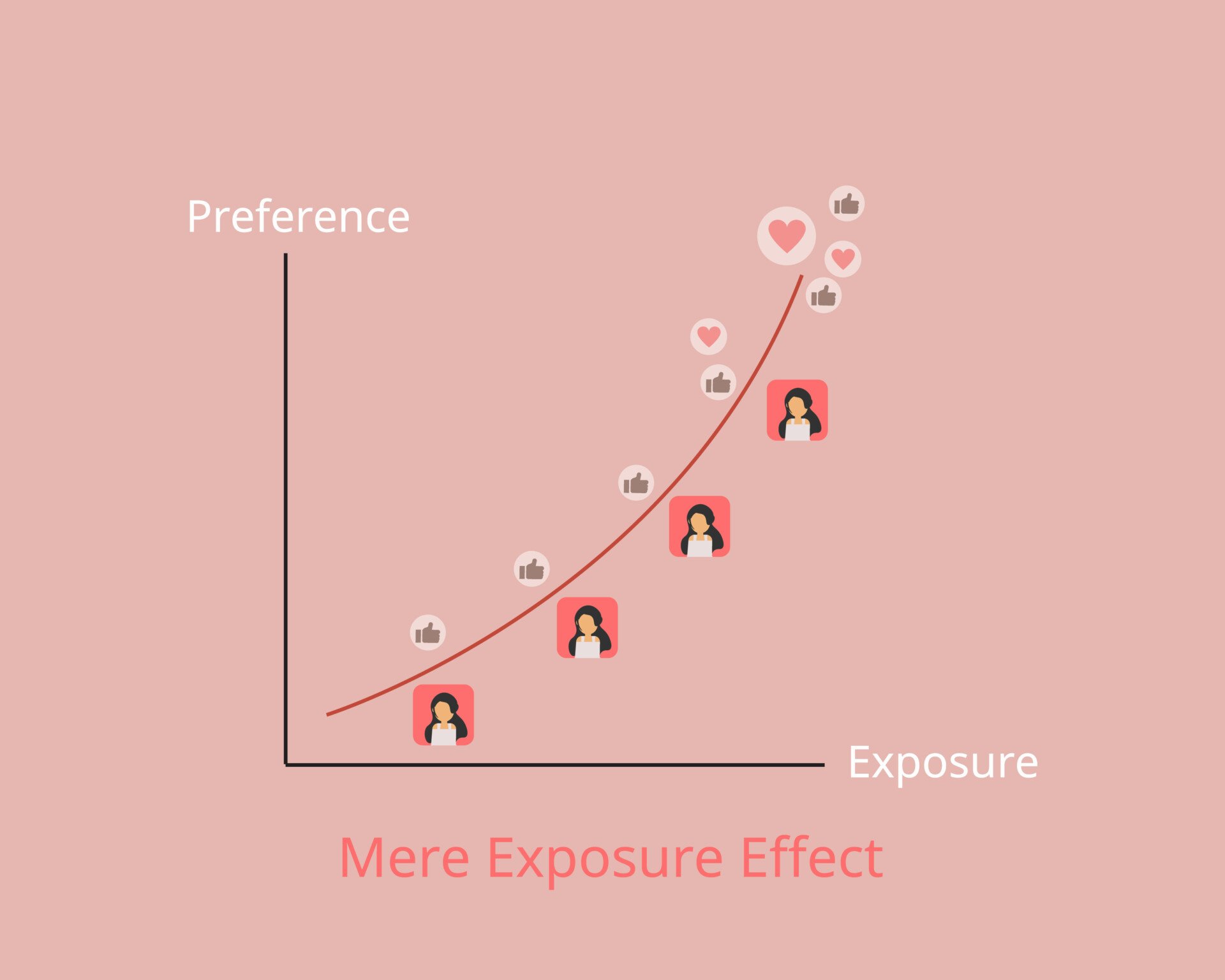

The mere exposure effect is a cognitive bias where individuals show a preference for things they’re more familiar with. Repeated exposure to a stimulus increases liking and familiarity, even without conscious recognition. Essentially, the more we encounter something, the more we tend to prefer it, based on familiarity alone.

Summary

- According to the mere exposure effect, people show an increased liking for stimuli as they are exposed to them more. This effect is logarithmic; the first few exposures someone has to a stimulus are more potent than later ones.

- Robert Zajonc devised the mere exposure effect through three types of supporting studies. These studies involved word frequency and word evaluation, interpersonal contact and interpersonal attraction, and musical frequency and liking.

- Other factors, such as initial familiarity and discriminability, can also influence the extent to which the mere exposure effect takes hold.

- The mere exposure effect sees implications in contexts ranging from art and architecture to advertising.

History and Overview

The mere exposure effect finds that people show an increased preference or liking for a stimulus the more that they are exposed to that stimulus.

This effect is most likely to happen when individuals have no pre-existing negative attitude toward the stimulus and tends to be strongest when they are not aware of the stimulus presented to them.

The first scientist to identify the mere exposure effect was Robert Zajonc. According to Zajonc’s mere exposure hypothesis, the repeated exposure of an individual to a stimulus is sufficient for that individual to develop a more enhanced attitude toward that stimulus.

Zajonc suggests that the relationship between exposure and liking has the shape of a positive, decelerating curve. The more someone is exposed to a stimulus, the more they like it, but the first few exposures are much more powerful than later ones (Zajonc, 1968).

Zajonc termed the phenomenon the “mere” exposure effect because this exposure can involve any conditions that make the stimulus perceptible to the organisms.

The hypothesis allows for other bases for liking without repetition, and that liking that derives from increased exposure can be offset by other factors.

It also does not require nor completely exclude other effects of familiarity with a stimulus.

Zajonc’s Evidence for the Mere Exposure Effect

To support his hypothesis, Zajonc discussed three types of supporting studies (1968).

These studies studied word frequency and the evaluation of that word, interpersonal contact and interpersonal attraction, and the familiarity of musical selections and other stimuli to people expressing a liking for them (Harrison, 1977).

Word Frequency and Word Evaluation

Studies have found correlations between word frequency (typically obtained from Thorndike-Lorge’s (1944) count) and how people view the word’s connotation.

These experimental studies have used techniques such as varying the number of times words are shown to participants and then assessing the participant’s attitudinal reactions.

Early studies investigating the relationship between frequency and meaning reported findings such as how so-called “dirty words” had higher recognition thresholds than neutral words (McGinnies, 1949).

More generally, Howes and Solomon (1950, 1951) showed that infrequent words have higher thresholds for recognition than frequent words and explained McGinniee’s findings in terms of the relative infrequency of “dirty words” in print (Harrison, 1977).

However, R.C. Johnson, Thomson, and Frincke (1960) were the first to raise the possibility of a relationship between word frequency and meaning.

The researchers found that more frequent words tended to have more favorable connotations than less frequently used words.

In 26 of 30 pairs of words, the high-frequency member was chosen to have a more positive connotation than the less frequent word, and nonsense words with familiar English-language letter combinations tended to receive more favorable ratings than nonsense words that did not contain familiar letter combinations.

To add to this prior research, Zajonc (1968) asked students to indicate which members of 154 pairs of antonyms had the most favorable meanings.

He found that over 80% of the time, the high-frequency member tended to be designated as more favorable.

Zajonc also reported that the most favorable adjectives in Gough’s (1955) list of adjectives had a higher frequency than less favorable adjectives and that the most positive personality descriptive adjectives had much higher rates of frequency than negative adjectives (Anderson, 1968; Zajonc, 1968; Harrison, 1977).

Zajonc found similar effects with letters combined with numbers, where more frequent (i.e., lower) numbers tended to be treated more favorably than low-frequency numbers.

However, it must be noted that these studies do not provide definitive support for the mere exposure hypothesis. For example, people’s liking and more positive connotations of high-frequency words may not be the result of exposure leading to liking, but liking a stimulus increases the probability that it will be discussed.

Indeed, according to the “Pollyanna hypothesis,” people have a universal tendency to structure their conceptual worlds in a positive way by referring more to pleasant than unpleasant things and events (Boutcher and Osgood, 1969; Matlin and Stang, 1976; Osgood, 1964; Harrison, 1977).

Interpersonal Contact and Interpersonal Attraction

Zajonc also discussed two lines of research instigated prior to his paper on the mere exposure hypothesis that suggested a link between exposure and interpersonal attraction.

First of all, studies of the relationship between proximity and friendship show that people who are physically close to each other and thus likely to come into repeated contact often become friends (Festinger, Schacter, and Back, 1950; Priest and Sawyer, 1967; Segal, 1974).

Secondly, studies into race relations have suggested that interracial contact can lead to a reduction in prejudice, even when factors such as status inequality, competition, and cultural customs can limit this effect (Allport, 1954; Amir, 1969; Deutsch and Collins, 1951; Pettigrew, 1971).

Studies have shown, in general, that there is a correlation between familiarity and liking for individuals and groups.

For example, Harrison (1969), in studying liking ratings of 200 public figures and of 40 fabricated individuals, correlated strongly with their exposure to printed media, and Stang (1975a) found that the ratings of presidents in the United States correlated strongly with how much their names were published in archival sources.

Additionally, many experiments on the effects of exposure on attraction have focused on the effect. In one such experiment, Stang (1974a) posted either 0, 20, or 200 posters asking students to elect a fictitious person to the editorship of a student publication.

Those who had seen the postures were more likely to vote for the publicized candidate. In another study using photographs, L. R. Wilson and Nakajo (1966) found that increasing the number of times a person’s photograph was shown led to increasingly favorable ratings of personality, social appeal, and emotional stability.

To corroborate this evidence, Zajonc (1968) used pictures of men’s graduation portraits and showed them either 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, or 25 times. Those who saw the graduation portraits tended to rate the person more favorably “as a person” (Harrison, 1977).

Hmm, Baum and Nickels (1975), extending Zijonc’s original study, found that these stimulus effects also applied to women and racial minorities.

Musical Selection Familiarity and Liking

In contrast to the word frequency and interpersonal exposure studies discussed before, many studies investigating the effects of exposure to reactions to musical selections have shown that low and intermediate-frequency stimuli tend to be the best-liked (Harrison, 1977).

Several studies on the mere exposure effect have shown that the more people are exposed to unfamiliar music, the more positively they tend to rate it (Bornstein and Lemly, 2017).

Nonetheless, there is a long lineage of studies demonstrating the mere exposure effect in music. One of the earliest of these, Meyer (1903), showed that when a novel composition was played several times, people were four times more likely to increase their liking of the composition than decrease their liking.

However, other evidence has contradicted the mere exposure effect. For example, Jakobovits (1966), using music sales as a proxy for liking, found that as popular music was aired more and more frequently on radios, there were increased following decreased sales (that is, liking) for their music.

However, sales could have dwindled for other reasons, such as all fans buying a copy of the song. Perhaps more compellingly, Bush and Pease (1968) found that playing a song 30 times in succession led to the increased polarization of ratings, with more individuals shifting negative than positive, and Shaife (1966) found that exposure can lead to either increased or decreased liking depending on the selections (Harrison, 1977).

Other Factors Leading to Increased Likeability

Although there are many studies presenting what appear to be mere exposure effects, controversy has arisen from their reproducibility. Harrison (1977) presents a number of variables that may lead to some studies yielding mere exposure effects while others have not.

He argues that so-called stimulus variables, presentation variables, and measurement variables interact with exposure to determine liking.

Whether or not an exposure effect is observed can partly depend on the properties of the stimuli that have been selected.

Stimulus variables can include initial or preexposure familiarity, initial or pre-exposure meaning, discriminability, recognizability, and complexity (Harrison, 1977).

Initial Familiarity

If a stimulus is already familiar, manipulating how much someone is exposed to it is unlikely to enhance that person’s attitude. For example, in a Washburn (1927) et al. study, mere exposure effects diminished or were eliminated when the selections were initially familiar rather than a novel.

In a similar way, Maslow (1937) found exposure effects for initially novel paintings and names but was not able to influence attitudes by varying the exposure of already familiar objects (Harrison, 1977).

Initial Meaning

Hypotheses also suggest that the mere exposure effect depends on the stimulus’s meaning prior to when people are exposed to it.

These hypotheses assume that the exposure effect reflects changes in meaning that do not reflect how that person evaluates the stimulus (Grush, 1976; Jakobovits, 1968; Harrison, 1977).

For example, the semantic satiation hypothesis posits that stimulus repetition leads to a loss of meaning, resulting in initially negatively toned stimuli becoming less negative with exposure, while initially, positively toned stimuli become less pleasing with repetition.

In contrast, the semantic generation interpretation suggests that exposure leads to increases in meaning in a way that initially positively toned stimuli become more positive overexposure while initially disliked stimuli become more negatively toned overexposure (Harrison, 1977).

Discriminability

Zajonnc, Shaver, Tavrrris, and VanKreveld (1972) noted that paintings shown once prior to being rated were better-liked than novel paintings.

However, they also found that ratings decreased as exposure further increased.

A second experiment from the researchers revealed that although exposure led to an increased and then increased liking for both similar and dissimilar stimuli, maximum liking for the less-discriminable stimuli required a greater number of exposures (Harrison, 1977).

Recognizability

Researchers have argued for and against recognizability as a cause of the mere exposure effect.

For example, Moreland (1975) had subjects rate stimuli according to how recognizable and familiar stimuli were. Repetition led to an increase in recognition, greater confidence in recognition judgments, greater subjective familiarity, and greater liking.

However, other analyses have demonstrated that the objective frequency of exposure may be the best predictor of liking, while subjective ratings of familiarity and recognition did not explain liking.

Complexity

Reducing the complexity of a stimulus can also lower the likelihood of an exposure effect.

Again, as Skaife (1966) found, while the repetition of a simple tune leads to less favorable reactions, the repetition of a complex song can yield exposure effects.

Berlyne, meanwhile, found greater declines over exposure when the stimuli were simple rather than complex.

Context

The ways in which stimuli are presented may also influence exposure effects.

Exposure does not occur in a vacuum, and thus, the affective reactions elicited by a situation or context in which exposure occurs can become increasingly associated with the exposure stimuli as exposure progresses.

Therefore, if a stimulus is presented in a context that elicits unpleasant emotional reactions, exposure should lead to a decreased liking for that stimulus and vice versa (Burgess and Sales, 1971).

To test this hypothesis, M. A. Johnson (1973) treated participants harshly and perched them on hard stools in a room that smelled of formaldehyde where the temperature was 35 degrees Celsius and still found that there were positive exposure effects comparable to the one in the condition where the unfavorable conditions had not been imposed.

In another study, Saaegert et al. (1973) had women move from cubicle to cubicle and encountered each other varying numbers of times. The exposure led to increased interpersonal attraction both in conditions where subjects tested pleasant solutions and in ones where they sampled bitter concoctions.

Context studies have gone beyond merely mere exposure. For example, Zajonc et al. (1974) showed that after showing photos of people labeled as either criminals or contributors (those who had significant scholarly or scientific achievements).

Those in the condition where the image of the criminal and contributor was reinforced (such as by showing a photo of the crime) tended to develop more favorable ratings of the contributors had less favorable but tampered ratings of the criminals; meanwhile, in the condition where this was not enforced, both the criminals and contributors receive more favorable ratings over time (Harrison, 1969).

Overall, these studies on context show that mere exposure and associative learning effects are independent and additive.

Exposure to a negative context can lead to disliking, but the mere exposure effect serves to inhibit this decline (Harrison, 1969).

Presentation Sequence

Exposing a stimulus within a “heterogeneous “ sequence — one where other stimuli are interspersed — is more likely to result in an exposure effect than one where a “homogeneous” or uninterrupted sequence with the stimulus is presented.

Berylune (1970) was one of the first to provide experimental evidence showing that high-frequency stimuli declined in judged pleasantness more rapidly when presented in homologous sequences (Harrison, 1969).

Illustrative Examples

Exposure to New Types of Art

When the paintings of impressionists, such as Claude Monet, were first displayed, they received scathing reviews. Similarly, wide criticism followed the display of early Cubist and Expressionist works.

However, with time — and repeated viewings — aesthetic judgments shift, and attitudes regarding the now-familiar style become more positive (Bornstein and Craver-Lemly, 2017).

Architecture

Harrison (1977) begins his text on the mere-exposure effect with an anecdote about the Eiffel Tower, one of the world’s most iconic and “seemingly best-loved” structures (Coutaud and Duclair, 1956).

However, despite its widespread admiration today, the Eiffel Tower’s construction was met with “a storm of protest” (DeVries, 1972). This early condemnation, according to scholars, was near-universal and nearly led to the tower’s demolition in the early 1900s (Coutaud and Duclair, 1956).

Harrison (1977) argues that the vastly shifting attitudes about the structure resulted from the mere exposure effect. The tower was ubiquitous and inescapable and likely to be seen day after day.

It soon became a familiar part of the skyline and thus, according to the mere-exposure hypothesis formulated by Zajonc, more widely liked (Zajonc, 1968; Harrison, 1977).

Advertising

One of the widest applications of the mere exposure effect is in product sales.

Marketing researchers have incorporated findings from research on mere exposure into a number of contemporary advertising campaigns (Janiszewski, 1993; Ruggieri and Boca, 2013; Bornstein and Craaver-Lemly, 2017).

Janiszewski (1993), for example, found that mere exposure to a brand name or product package can encourage a consumer to have a more favorable attitude toward the brand.

Even when the consumer cannot recollect the initial exposure and investigate why the mere exposure effects persist when these initial exposures to brand names and product packages are incidental and devoid of an intentional effort to process the brand information.

Ultimately, the researcher finds that these unintentional mere exposure effects are attributable to preattentive processes and, specifically, hemispheric processing theory — a theoretical framework for explaining how each of the brain’s hemispheres contributes to language and how people interpret words.

References

Allport, G. W., Clark, K., & Pettigrew, T. (1954). The nature of prejudice.

Amir, Y. (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations. Psychological Bulletin, 71(5), 319–342.

Anderson H, N. (1968). Likableness Ratings of 555 Personality – Trait Words. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(3), 272–279.

Berlyne, D. E. (1970). Novelty, complexity, and hedonic value. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics. Psychonomic Journals, 8(5A), 279–286.

Bornstein, R. F., & Craver-Lemley, C. (2017). Mere exposure effect. In R. F. Pohl (Ed.), Cognitive illusions: Intriguing phenomena in thinking, judgment and memory 256–275

Boucher, J., & Osgood, C. E. (1969). The pollyanna hypothesis. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 8(1), 1–8.

Burgess II, T. D., & Sales, S. M. (1971). Attitudinal effects of “mere exposure”: A reevaluation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7(4), 461-472.

Bush, P. A., & Pease, K. G. (1968). Pop records and connotative satiation: Test of Jakobovits’ theory. Psychological Reports, 23(3), 871-875.

Coutaud, R., & Duclair, J. H. (1956). Paris dans votre poche. Paris: Edition Touristiques Francaises.

Deutsch, M., & Collins, M. E. (1951). Interracial housing: A psychological evaluation of a social experiment. U of Minnesota Press.

De Vries, L., & Van Amstel, I. (1972). Victorian inventions. New York: American Heritage Press.

Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. (1950). Social pressures in informal groups; a study of human factors in housing.

Gough, H. G. (1955). Reference handbook for the Gough adjective check list. Berkeley: University of California Institute of Personality Assessment and Research

Grush, J. E. (1976). Attitude formation and mere exposure phenomena: A nonartifactual explanation of empirical findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33(3), 281.

Harrison, A. A. (1969). Exposure and popularity. Journal of Personality 37, 359-377.

Harrison, A. A. (1977). Mere Exposure. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 10(C), 39–83.

Howes, D. H., & Solomon, R. L. (1950). A note on McGinnies’ “Emotionality and perceptual defense.” Psychological Review, 57(4), 229–234.

Howes, D. H., & Solomon, R. L. (1951). Visual duration threshold as a function of word-probability. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 41(6), 401–410.

Janiszewski, C. (1993). Preattentive Mere Exposure Effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), 376.

Jakobovits, L. A. (1966). Studies of fads: I. the “Hit Parade”. Psychological Reports, 18(2), 443-450.

Jakobovits, L. A. (1968). Effects of mere exposure: A comment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2), 30-32.

Johnson, R. C., Thomson, C. W., & Frincke, G. (1960). Word values, word frequency, and visual duration thresholds. Psychological Review, 67(5), 332–342.

Johnson, M. A. (1973, April). The attitudinal effects of mere exposure and the experimental environment. In meeting of the Western Psychological Association, Anaheim, Cahf.

Maslow, A. H. (1937). The influence of familiarization on preference. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 21(2), 162.

Matlin, M. W ., & Stang, D. J. (1976). The Pollyanna principle: Affect and evaluation in language, memory and cognition. In preparation.

McGinnies, E. (1949). Emotionality and perceptual defense. Psychological Review, 56(5), 244–251.

Meyer, M. (1903). Experimental studies in the psychology of music. The American Journal of Psychology, 14(3/4), 192-214.

Moreland, R. L., & Zajonc, R. B. (1977). Is stimulus recognition a necessary condition for the occurrence of exposure effects?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(4), 191.

Osgood, C. E. (1964). Semantic differential technique in the comparative study of cultures 1. American Anthropologist, 66(3), 171-200.

Pettigrew, T. F. (1969). Racially Separate or Together? Journal of Social Issues, 25(1), 43–70.

Priest, R. F., & Sawyer, J. (1967). Proximity and peership: bases of balance in interpersonal attraction. American Journal of Sociology, 72(6), 633–649.

Ruggieri, S., & Boca, S. (2013). At the roots of product placement: The mere exposure effect. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 9(2), 246–258.

Saegert, S., Swap, W., & Zajonc, R. B. (1973). Exposure, context, and interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25(2), 234.

Segal, M. W. (1974). Alphabet and attraction: An unobtrusive measure of the effect of propinquity in a field setting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30(5), 654–657.

Skaife, A. M. (1967). The role of complexity and deviation in changing taste. unpublished Ph. D. thesis, University of Oregon.

Solomon, R. L., & Howes, D. H. (1951). Word frequency, personal values, and visual duration thresholds. Psychological Review, 58(4), 256–270.

Stang, D. J. (1974a). An analysis of the effects of political campaigning. [Conference presentation]. Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology 66th annual meeting, Tampa.

Stang, D. J. (1975a, August). Is learning necessary for the attitudinal effects of mere exposure? [Conference presentation]. American Psychological Association Annual meeting

Thorndike, E. L., & Lorge, I. (1944). The teacher’s word book of 30,000 words.

Washburn, M. F., Child, M. S., & Abel, T. M. (1927). The effects of immediate repetition on the pleasantness or unpleasantness of music. The effects of music, 199-210.

Wilson, W., & Nakajo, H. (1965). Preference for photographs as a function of frequency of presentation. Psychonomic Science, 3(1), 577-578.

Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9(2p2), 1.

Zajonc, R. B., Shaver, P., Tavris, C., & Van Kreveld, D. (1972). Exposure, satiation, and stimulus discriminability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 21(3), 270.

Zajonc, R. B., Crandall, R., Kail Jr, R. V., & Swap, W. (1974). Effect of extreme exposure frequencies on different affective ratings of stimuli. Perceptual and motor skills, 38(2), 667-678.