The term minority influence refers to a form of social influence that is attributed to exposure to a consistent minority position in a group.

Minority influence is generally felt only after a period of time and tends to produce private acceptance of the views expressed by the minority.

An important real-life example of a minority influencing a majority was the suffragette movement in the early years of the 20th century.

A relatively small group of suffragettes argued strongly for the initially unpopular view that women should be allowed to vote. The hard work of the suffragettes, combined with the justice of their case, finally led the majority to accept their point of view.

Conformity studies involve a minority group that conforms to the majority. Moscovici (1976, 1980) argued along different lines. He claimed that Asch (1951) and others had put too much emphasis on the notion that the majority in a group has a large influence on the minority. In his opinion, it is also possible for a minority to influence the majority.

In fact, Asch agreed with Moscovici. He, too, felt that minority influence did occur and that it was potentially a more valuable issue to study – to focus on why some people might follow minority opinions and resist group pressure.

Moscovici made a distinction between compliance and conversion. Compliance is common in conformity studies (e.g., Asch) whereby the participants publicly conform to the group norms but privately reject them.

Conversion involves how a minority can influence the majority. It involves convincing the majority that the minority views are correct. This can be achieved a number of different ways (e.g., consistency and flexibility).

Conversion is different from compliance as it usually involves both public and private acceptance of a new view or behavior (i.e., internalization).

How does the minority change the majority view?

Moscovici argues that majority influence tends to be based on public compliance. It is likely to be a case of normative social influence.

In this respect, the power of numbers is important – the majority has the power to reward and punish with approval and disapproval. And because of this, there is pressure on minorities to conform.

Since majorities are often unconcerned about what minorities think about them, minority influence is rarely based on normative social influence. Instead, it is usually based on informational social influence – providing the majority with new ideas and new information, which leads them to re-examine their views.

In this respect, minority influence involves private acceptance (i.e., internalization)- converting the majority by convincing them that the minority’s views are right.

Four main factors have been identified as important for a minority to have an influence over a majority.

These are behavioral style, style of thinking, flexibility, and identification.

behavioral Style

This comprises four components:

1. Consistency: The minority must be consistent in their opinion

2. Confidence in the correctness of ideas and views they are presenting

3. Appearing to be unbiased

4. Resisting social pressure and abuse

Moscovici (1969) stated that the most important aspect of behavioral style is the consistency with which people hold their position. Being consistent and unchanging in a view is more likely to influence the majority than if a minority is inconsistent and chops and changes their mind.

Moscovici (1969) investigated behavioral styles (consistent/inconsistent) on minority influence in his blue-green studies. He showed that a consistent minority was more successful than an inconsistent minority in changing the views of the majority. Consistency may be important because:

- Confronted with consistent opposition, members of the majority will sit up, take notice, and rethink their position.

- Consistency gives the impression that the minority are convinced they are right and are committed to their viewpoint.

- Also, when the majority is confronted with someone with self-confidence and dedication to take a popular stand and refuses to back own, they may assume that he or she has a point.

- A consistent minority disrupts established norms and creates uncertainty, doubt, and conflict. This can lead to the majority taking the minority view seriously. The majority will therefore be more likely to question their own views.

In order to change the majority’s view, the minority has to propose a clear position and has to defend and advocate its position consistently.

A distinction can be made between two forms of consistency:

(a) Diachronic Consistency – i.e., consistency over time – the majority stocks to its guns and doesn’t modify its views.

(b) Synchronic Consistency – i.e., consistency between its members – all members agree and back each other up.

Style of Thinking

Identify three or four minority groups (e.g., asylum seekers, British National Party, etc.)

How do you think and respond to each of these minority groups and the views they put forward?

Do you dismiss their views outright or think about what they have to say and discuss their views with other people?

If you dismiss the views of other people without giving them much thought, you would have engaged in superficial thought/processing.

By contrast, if you had thought deeply about the views being put forward, you would have engaged in systematic thinking/processing (Petty et al., 1994).

Research has shown that if a minority can get the majority to think about an issue and think about arguments for and against it, then the minority stands a good chance of influencing the majority (Smith et al., 1996).

If the minority can get the majority to discuss and debate the arguments that the minority is putting forward, influence is likely to be stronger (Nemeth, 1995).

Flexibility and Compromise

A number of researchers have questioned whether consistency alone is sufficient for a minority to influence a majority. They argue that the key is how the majority interprets consistency.

If the consistent minority is seen as inflexible, rigid, uncompromising, and dogmatic, they will be unlikely to change the views of the majority. However, if they appear flexible and compromising, they are likely to be seen as less extreme, as more moderate, cooperative and reasonable. As a result, they will have a better chance of changing the majority views (Mugny & Papastamou, 1980).

Some researchers have gone further and suggested that it is not just the appearance of flexibility and compromise, which is important, but actual flexibility and compromise.

This possibility was investigated by Nemeth (1986). The experiment was based on a mock jury in which groups of three participants and one confederate had to decide on the amount of compensation to be given to the victim of a ski-lift accident.

When the consistent minority (the confederate) argued for a very low amount and refused to change his position, he had no effect on the majority. However, when he compromised and moved some way towards the majority position, the majority also compromised and changed their view.

This experiment questions the importance of consistency. The minority position changed, it was not consistent, and it was this change that apparently resulted in minority influence.

Identification

People tend to identify with people they see as similar to themselves. For example, people of the same gender, ethnic group, or age.

Research indicates that if the majority identifies with the minority, then they are more likely to take the views of the minority seriously and change their own views in line with those of the minority.

For example, one study showed that a gay minority arguing for gay rights had less influence on a straight majority than a straight minority arguing for gay rights (Maass et al., 1982).

The non-gay majority identified with the non-gay minority. They tended to see the gay minority as different from themselves, as self-interested and concerned with promoting their own particular cause.

Moscovici et al. (1969) Blue-Green Study

Aim: To investigate the effects of a consistent minority on a majority. Moscovici (1969) conducted a re-run of Asch’s experiment, but in reverse.

Instead of one subject amongst a majority of confederates, he placed two confederates together with four genuine participants. The participants were first given eye tests to ensure they were not color-blind.

Procedure: They were then placed in a group consisting of four participants and two confederates. They were shown 36 slides which were clearly different shades of blue, and asked to state the color of each slide out loud.

In the first part of the experiment, the two confederates answered green for each of the 36 slides. They were totally consistent in their responses. In the second part of the experiment, they answered green 24 times and blue 12 times.

In this case, they were inconsistent in their answers. Would the responses of the two confederates influence those of the four participants? In other words, would there be a minority influence?

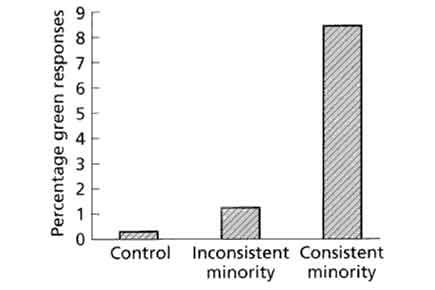

Results: In condition one, it was found that the consistent minority had an effect on the majority (8.42%) compared to an inconsistent minority (only 1.25% said green).

A third (32%) of all participants judged the slide to be green at least once.

Conclusion: Minorities can influence a majority, but not all the time, and only when they behave in certain ways (e.g., consistent behavior style).

Criticism: The study used lab experiments – i.e., are the results true to real life (ecological validity)? Also, Moscovici used only female students as participants (i.e., an unrepresentative sample), so it would be wrong to generalize his result to all people – they only tell us about the behavior of female students.

Evaluation

Most of the research on minority influence is based on experiments conducted in laboratories. This raises the question of ecological validity. Is it possible to generalize the findings of laboratory research to other settings? Edward Sampson (1991) is particularly critical of laboratory research on minority influence. He makes the following points.

The participants in laboratory experiments are rarely “real groups.” More often than not, they are a collection of students who do not know each other and will probably never meet again. They are also involved in an artificial tasks. As such, they are very different from minority groups in the wider society who seek to change majority opinion.

For example, members of women’s rights, gay rights, and animal rights organizations, and members of pressure groups such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth are very different from participants in laboratory experiments. They operate in different settings with different constraints.

They often face much more determined opposition. They are committed to a cause; they often know each other, provide each other with considerable social support and sometimes devote their lives to changing the views of the majority. Power and status laboratory experiments are largely unable to represent and simulate the wide differences in power and status that often separate minorities and majorities.

Also, Moscovici (1969) used only female students as participants (i.e., an unrepresentative sample ), so it would be wrong to generalize his result to all people – they only tell us about the behavior of female students.

Also, females are often considered to be more conformist than males. Therefore, there might be a gender difference in the way that males and females respond to minority influence. Another criticism could be that four people are not enough for a group and could not be considered as the majority.

References

Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgment. In H. Guetzkow (ed.) Groups, leadership and men. Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press.

Moscovici, S. and Zavalloni, M. (1969). The group as a polarizer of attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 12, 125-135.

Moscovici, S. (1976). Social influence and social change. London: Academic Press.

Moscovici, S. (1980). Toward a theory of conversion behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 13, (pp. 209–239). New York: Academic Press.

Mugny, G., & Papastamou, S. (1980). When rigidity does not fail: Individualization and psychologization as resistances to the diffusion of minority innovations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 10(1), 43-61.

Nemeth, C. J. (1986). The differential contributions of majority and minority influence. Psychological Review, 93, 23-32.

Sampson, E. (1991). Social worlds, personal lives: An introduction to social psychology. (6th Ed.) San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Smith, C. M., Tindale, R. S., & Dugoni, B. L. (1996). Minority and majority influence in freely interacting groups: Qualitative versus quantitative differences. British Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 137–149.

Trost, M. R., Maass, A., & Kenrick, D. (1992). Minority influence: Personal relevance biases cognitive processes and reverses private acceptance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28,234-254.