Key Takeaways

- In negative reinforcement, first devised by B. F. Skinner, an undesirable stimulus is removed to increase a behavior.

- If an organism is exposed to an aversive situation, and the termination of that situation is made contingent upon some response, then we say that the organism is being negatively reinforced.

- There are two types of negative reinforcement: escape and avoidance learning. Escape learning occurs when an animal performs a behavior to end an aversive stimulus, while avoidance learning involves performing a behavior to prevent the aversive stimulus.

- Negative reinforcement can be effective, but scholars generally agree that it must be used sparingly and is best for reinforcing short-term behaviors.

How Does It Work?

Negative reinforcement refers to the process of removing an unpleasant stimulus after the desired behavior is displayed in order to increase the likelihood of that behavior being repeated.

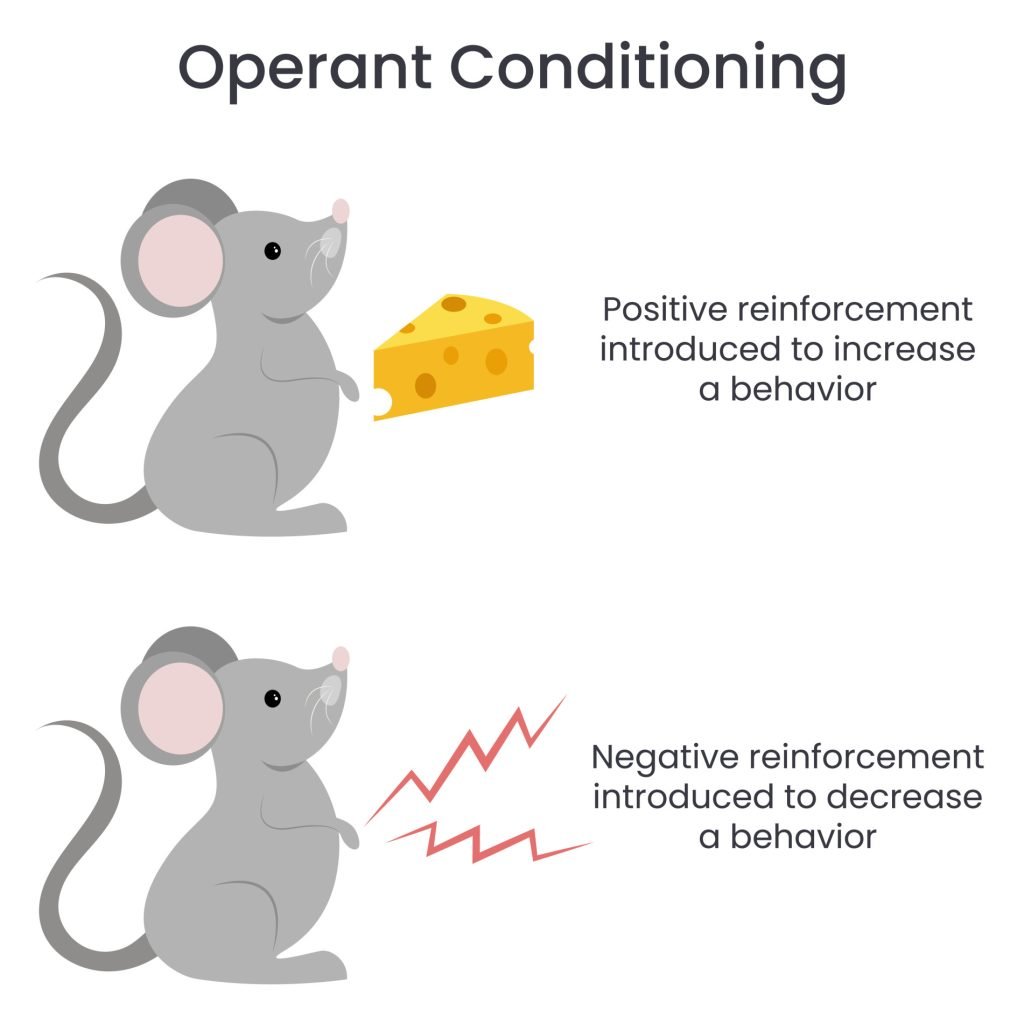

Negative reinforcement is a basic principle of Skinner’s operant conditioning, which focuses on how animals and humans learn by observing the consequences of their own actions (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

Skinner argued that learning is an active process. When humans and animals act on and in their environment, consequences follow these behaviors. If the consequences are pleasant, they repeat the behavior, but if the consequences are unpleasant, they do not repeat the behavior.

The word “negative” in the phrase “negative reinforcement” means simply to “take something away. It is this removal of a stimulus that is intended to strengthen a desirable behavior.

Thus, negative reinforcement is not intended to reinforce negative or undesirable behavior (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

Negative reinforcement occurs when performing an action stops something unpleasant from happening. For example, in one of Skinner’s experiments, a rat had to press a lever to stop receiving an electric shock.

Example

One example of negative reinforcement that often appears in adult life involves driving. Imagine that someone is driving to work and is running late.

The driver sees that the speed limit is 55 mph but decides to go 65 mph so that they can get to work on time.

Suddenly, they see a police car in their rearview mirror with its lights on. The aversive stimulus (getting pulled over) is now present, and so they slow down to the speed limit.

In this case, the desired behavior (driving the speed limit) has occurred as a result of the aversive stimulus (getting pulled over).

In another scenario, someone could drive through rush hour traffic to get to work.

Their commute could take an hour or more, and it is very stressful. They may decide to leave work early one day so that they can avoid the traffic.

Alternatively, they may decide to take a route that has very little traffic and make it to work in 45 minutes.

That person, after getting the same results later in the week, may start taking this new route everyday. In this case, removing the negative stimulus of bad traffic changes the behavior of the driver (Chen, Zhang, Gong, & Lee, 2019).

Types of Negative Reinforcement

There are two main types of negative reinforcement: escape and avoidance. These differ when the aversive stimulus is removed.

Escape Learning

Escape learning occurs when an animal performs a behavior (such as pressing a lever) to stop or avoid an aversive stimulus (such as an electric shock) (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

For example, a rat in a Skinner box may learn to press a lever to stop the delivery of an electric shock.

Once the animal has learned this behavior, the delivery of shock serves as an aversive stimulus that can be used to reinforce other desired behaviors (such as pressing a different lever).

Avoidance Learning

Avoidance learning occurs when an animal performs a behavior (such as jumping over a hurdle) to avoid or escape an aversive stimulus (such as an electric shock).

For example, a bird in a laboratory experiment may learn to go into a dark compartment to avoid being exposed to a loud noise.

Once the animal has learned this behavior, the loud noise serves as an aversive stimulus that can be used to reinforce other desired behaviors (such as going into dark compartments, even when there is no aversive stimulus present) (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

How is it different than punishment?

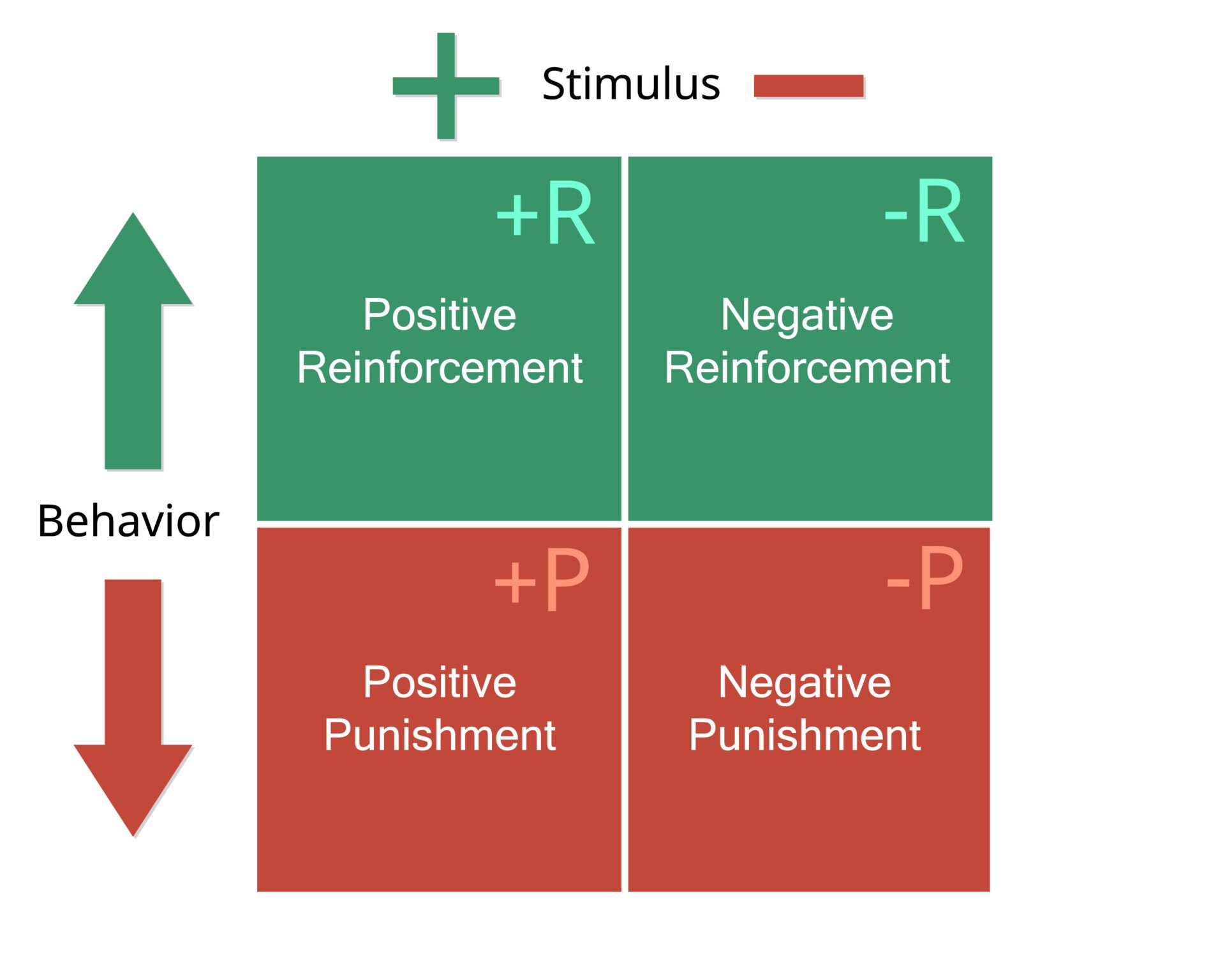

Many people confuse negative reinforcement with punishment in operant conditioning, but they are two very different mechanisms.

Remember that reinforcement, even when it is negative, always increases a behavior. In contrast, punishment always decreases behavior.

Negative reinforcement, on the other hand, removes an unpleasant condition after a desired behavior is displayed to increase the likelihood of that behavior being repeated in the future (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

Punishment involves bringing an unpleasant consequence after a behavior has already occurred to decrease its likelihood of happening again in the future.

For example, a child may lie about doing his chores, provoking his parents to give him extra chores. In this case, extra chores are an undesirable consequence to eliminate the behavior of lying.

As another example of punishment, a teacher may take away a student’s recess because they were talking too much in class.

This is not negative reinforcement because the teacher is taking away a positive consequence (recess) after the behavior (talking too much in class) has already occurred (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

All in all, punishment is intended to be an aversive stimulus that decreases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated, while negative reinforcement is intended to remove an aversive stimulus in order to increase the likelihood of a behavior being repeated.

Negative reinforcement is not the opposite of positive reinforcement

Both positive and negative reinforcement increases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated. The only difference is the type of consequence used to achieve this goal.

While positive reinforcement uses a desirable consequence to increase the likelihood of a behavior being repeated, negative reinforcement removes an unpleasant condition after the behavior is displayed in order to increase its future occurrence (Dozier, Foley, Goddard, & Jess, 2019).

For example, imagine a parent trying to potty train their child. Every time they use the toilet, the parent praises them and gives them a sticker.

This is an example of positive reinforcement because the parent is providing a desirable consequence (praise and stickers) after the desired behavior (using the toilet) has occurred to increase its future occurrence.

Now imagine that instead of praising and rewarding your child every time they use the toilet, the parent simply stops nagging them about it.

This is an example of negative reinforcement because you are removing an aversive stimulus (nagging) after the desired behavior (using the toilet) has occurred in order to increase its future occurrence.

In the classroom

Negative reinforcement can be used in any situation where behavior change needs to occur.

One common example of negative reinforcement in the classroom is when a teacher gives students extra credit for turning in their homework on time.

Imagine this is a scenario where students are avoiding turning in their homework on time because they wish to do it more thoroughly in order to avoid a lower grade.

In this case, the extra credit is intended to remove the unpleasant condition (receiving a poor grade) after the desired behavior (turning in homework on time) has occurred in order to increase its future occurrence (Gunter & Coutinho, 1997).

In this example, the extra credit is not given if the student does not turn in their homework on time. This is because negative reinforcement is only intended to work when it follows the desired behavior.

If the extra credit was given regardless of whether or not the homework was turned in on time, then it would simply be a reward and would not function as negative reinforcement.

Another common example of negative reinforcement in the classroom is when a teacher threatens to give students detention if they do not complete their homework.

In this case, the removal of the aversive stimulus (detention) is contingent on the desired behavior (completing homework) being displayed (Gunter & Coutinho, 1997).

Again, it is important to note that negative reinforcement should only be used after the desired behavior has already been displayed.

If students are given detention regardless of whether or not they complete their homework, then it is simply punishment and will not function as negative reinforcement.

Although this negative reinforcement could be effective in encouraging positive behavior, some researchers contend that positive reinforcement should be emphasized and negative reinforcement used sparingly.

They argue that focusing on the positive (e.g., rewarding students for completing their homework) is more likely to result in long-term behavior change than focusing on the negative (e.g., threatening students with detention if they do not complete their homework).

In this view, negative reinforcement is best for immediate behavioral changes (Gunter & Coutinho, 1997).

Effectiveness

Whether or not negative reinforcement is an effective way to change behavior depends on a number of factors, including the age and maturity of the learner, the severity of the aversive stimulus, and the desirability of the desired behavior.

Negative reinforcement can be particularly effective when the aversive stimulus is something that the learner genuinely wants to avoid.

For example, if a student is trying to study for an exam but is easily distracted by social media, using negative reinforcement (e.g., threatening to take away their phone if they do not study) could be an effective way to get them to focus on their work (Dad, Ali, Janjua, Shazad, & Khan, 2010).

However, if the aversive stimulus is not something that the learner cares about, then it is unlikely to be effective.

For example, if a student does not care about detention, then threatening them with detention is not likely to be an effective way to get them to do their homework.

In general, negative reinforcement is most effective when it is used sparingly and only for behaviors that are genuinely undesirable.

Using it too frequently or for minor infractions can result in the learner becoming Ortony, Clore, & Collins (1988) argue that punishment (including negative reinforcement) should only be used “as a last resort” after other methods of behavior change have failed (Dad, Ali, Janjua, Shazad, & Khan, 2010).

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Chen, C., Zhang, K. Z., Gong, X., & Lee, M. (2019). Dual mechanisms of reinforcement reward and habit in driving smartphone addiction: the role of smartphone features. Internet Research.

Dad, H., Ali, R., Janjua, M. Z. Q., Shahzad, S., & Khan, M. S. (2010). Comparison of the frequency and effectiveness of positive and negative reinforcement practices in schools. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 3 (1), 127-136.

Dozier, C. L., Foley, E. A., Goddard, K. S., & Jess, R. L. (2019). Reinforcement. The Encyclopedia of Child and Adolescent Development, 1-10.

Ferster, C. B., & Skinner, B. F. (1957). Schedules of reinforcement. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Gunter, P. L., & Coutinho, M. J. (1997). Negative reinforcement in classrooms: What we”re beginning to learn. Teacher Education and Special Education, 20 (3), 249-264.

Kohler, W. (1924). The mentality of apes. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. New York: Appleton-Century.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Superstition” in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 168-172.

Skinner, B. F. (1951). How to teach animals. Freeman.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human behavior. SimonandSchuster.com.

Skinner, B. F. (1963). Operant behavior. American Psychologist, 18 (8), 503.

Thorndike, E. L. (1898). Animal intelligence: An experimental study of the associative processes in animals. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 2(4), i-109.

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it. Psychological Review, 20, 158–177.