Societies work or function because each individual member of that society plays particular roles and each role carries a status and norms which are informed by the values and beliefs of the culture of that society.

The process of learning these roles and the norms and values appropriate to them from those around us is called socialisation.

How Are Norms and Values Different?

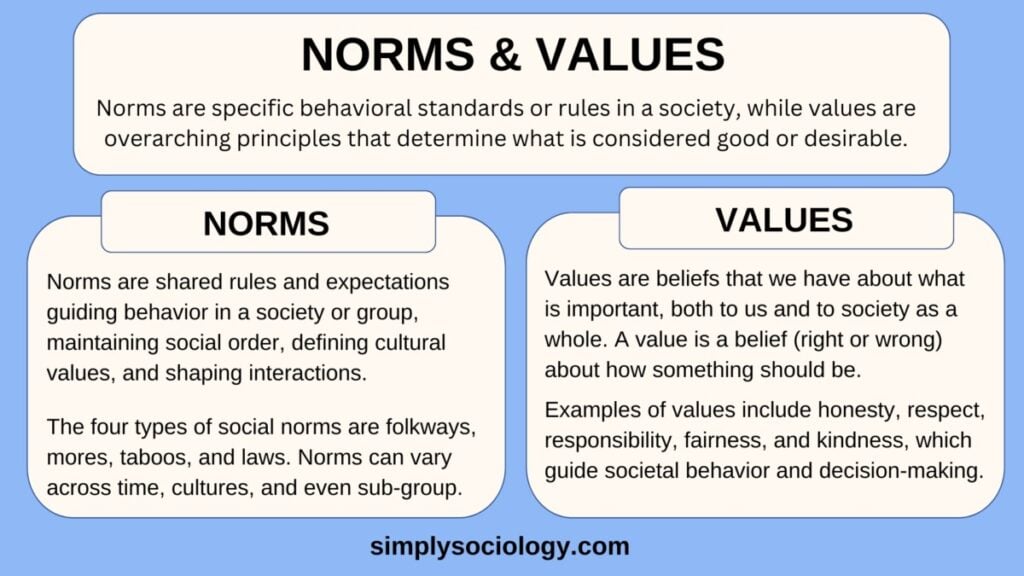

Values are the basic beliefs that guide the actions of individuals, while norms are the expectations that society has for people’s behavior. In other words, values tell individuals what is right or wrong, while norms tell individuals what is acceptable or not.

Values are more abstract and universal than norms, meaning they exist independently of any specific culture or society. Norms, on the other hand, are specific to a particular culture or society, and are essentially action-guiding rules, specifying concretely the things that must be done or omitted.

Additionally, values tend to be passed down from generation to generation, while norms can change relatively quickly.

In short, the values we hold are general behavioral guidelines. They tell us what we believe is right or wrong, for example, but that does not tell us how we should behave appropriately in any given social situation. This is the part played by norms in the overall structure of our social behavior.

However, there is often a lot of overlap between norms and values. For example, one of most of society’s norms is that one should not kill other people.

This norm is also a value, it is something that societies believe is morally wrong (McAdams, 2001).

What Are Norms?

Social norms are specific rules dictating how people should act in a particular situation, values are general ideas that support the norm”. There are four types of norm we can distinguish:

1. Folkways

Folkways are norms related to everyday social behavior that are followed out of custom, tradition, or routine. They are less strictly enforced than mores or laws, and violations are typically met with mild social disapproval rather than serious punishment.

Examples of folkways include etiquette and manners, such as holding a door open for someone, saying “please” and “thank you,” or not talking loudly in a library.

They contribute to the social order by facilitating smooth, predictable social interactions.

Folkways are fairly weak kinds of norm. For example, when you meet someone you know on the street, you probably say ”hello” and expect them to respond in a kind way.

If they ignore you, they have broken a friendship norm, which might lead you to reassess your relationship with them.

2. Mores

Mores are much stronger norms, and a failure to conform to them will result in a much stronger social response from the person or people who resent your failure to behave appropriately.

Mores refer to the norms that are widely observed and have great moral significance in a society. These norms are often seen as critical for the proper functioning of a group or society, and violations are typically met with serious societal disapproval or sanctions.

Mores often dictate ethical and moral standards in social behavior, such as honesty, respect for human life, and laws against theft or murder.

3. Taboos

Taboos refer to those behaviors, practices, or topics considered profoundly offensive, repugnant, and unacceptable by a society or cultural group.

Societal sanctions, penalties, or ostracism often back these prohibitions.

The origin of taboos can be traced to religious beliefs, societal customs, or moral codes, and they usually touch on areas such as sex, death, dietary habits, and social relations.

The violation of these taboos can lead to severe consequences, which might include social exclusion, legal repercussions, or even physical harm in extreme cases.

4. Laws (legal norms)

A law is an expression of a very strong moral norm that exists to control people’s behavior explicitly.

Punishment for the infraction of legal norms will depend on the norm that has been broken and the culture in which the legal norm develops.

Norms shape attitudes, afford guidelines for actions and establish boundaries for behavior. Moreover, norms regulate character, engender societal cohesion, and aid individuals in striving toward cultural goals.

Conversely, the violation of norms may elicit disapprobation, ridicule, or even ostracization. For instance, while the Klu Klux Klan is legally permitted in the United States, norms pervading many academic, cultural, and religious institutions barely countenance any association with it or any espousal of its racist and antisemitic propaganda.

Consequently, we see the potency of a norm condemning certain viewpoints being promoted through informal means even in the absence of any equivalent formal counterparts.

What Are Values?

Values are beliefs that we have about what is important, both to us and to society as a whole. A value, therefore, is a belief (right or wrong) about the way something should be.

Values are essential in validating norms; normative rules without reference to underlying values lack motivation and justification. Meanwhile, without corresponding norms, values lack concrete direction and execution (McAdams, 2001).

While the common values of societies can change overtime, this process is usually slow. This means these values tend to be appropriate for their historical period (Merton, 1994).

There are still commonly shared values within societies, but they become generalized, a more general underpinning for social practices.

Durkheim notes that value consensus continues to exist in modern societies but in a weaker form because industrialization has resulted in people having greater access to a greater variety of knowledge and ideas, e.g., through the mass media and science.

References

Barnard, A., & Burgess, T. (1996). Sociology explained. Cambridge University Press.

Berkowitz, A. D. (2005). An overview of the social norms approach. Changing the culture of college drinking: A socially situated health communication campaign, 1, 193-214.

Bicchieri, C. (2011). Social Norms. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Boudon, R. (2017). The origin of values: Sociology and philosophy of beliefs. Routledge.

Carter, P. M., Bingham, C. R., Zakrajsek, J. S., Shope, J. T., & Sayer, T. B. (2014). Social norms and risk perception: Predictors of distracted driving behavior among novice adolescent drivers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 54 (5), S32-S41.

Chung, A., & Rimal, R. N. (2016). Social norms: A review. Review of Communication Research, 4, 1-28.

Frese, M. (2015). Cultural practices, norms, and values. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46 (10), 1327-1330.

Hechter, M., & Opp, K. D. (Eds.). (2001). Social norms.

Lapinski, M. K., & Rimal, R. N. (2005). An explication of social norms. Communication theory, 15 (2), 127-147.

Merton, R. K. (1994, March). Durkheim”s division of labor in society. In Sociological Forum (Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 17-25). Kluwer Academic Publishers-Plenum Publishers.

Moi, T. (2001). What is a woman?: and other essays. Oxford University Press on Demand.

Reno, R. R., Cialdini, R. B., & Kallgren, C. A. (1993). The transsituational influence of social norms. Journal of personality and social psychology, 64 (1), 104.

Sunstein, C. R. (1996). Social norms and social roles. Colum. L. Rev., 96, 903.

Young, H. P. (2007). Social Norms.