Object permanence means knowing that an object still exists, even if it is hidden. It refers to the capacity to mentally represent objects that are not currently perceivable based on sensory input. Object permanence requires the ability to form a mental representation (i.e. a schema) of the object.

For example, if you place a toy under a blanket, the child who has achieved object permanence knows it is there and can actively seek it. At the beginning of this stage, the child behaves as if the toy had disappeared.

The attainment of object permanence generally signals the transition from the sensorimotor stage to the preoperational stage of development.

The Development of Object Permanence

According to seminal research by Piaget (1954), infants develop object permanence through a progression of substages in the sensorimotor period (birth to 2 years). These include:

Birth to 1 Month: Reflexes

Reflexive schemas form, where actions are repeated if pleasurable (Piaget, 1954). For example, an infant may suck their thumb by accident, but then repeat the action.

4 to 8 Months: Intentional Actions

Infants intentionally repeat actions to reproduce pleasurable environmental effects (secondary circular reactions), demonstrating intention and cause-and-effect reasoning (Baillargeon et al., 1985).

8 to 12 Months: Greater Exploration

Exploration and intentional actions become more coordinated as infants learn to produce desired outcomes (Spelke et al., 1992). For example, shaking a toy to make a sound.

12 to 18 Months: Trial and Error

Trial-and-error behaviors emerge as children begin to perform actions to elicit social responses (Diamond, 1985).

18 to 24 Months: Object Permanence Emerges

Representational thought develops, allowing infants to hold mental representations of unseen objects – demonstrating object permanence (Piaget, 1954; Wang et al., 2004).

Blanket and Ball Study

Aim: Piaget (1963) wanted to investigate at what age children acquire object permanence.

Method: Piaget hid a toy under a blanket, while the child was watching, and observed whether or not the child searched for the hidden toy.

Searching for the hidden toy was evidence of object permanence. Piaget assumed that the child could only search for a hidden toy if s/he had a mental representation of it.

Results: Piaget found that infants searched for the hidden toy when they were around 8-months-old.

Conclusion: Children around 8 months have object permanence because they can form a mental representation of the object in their minds.

Evaluation: Piaget assumed the results of his study occurred because the children under 8 months did not understand that the object still existed underneath the blanket (and therefore did not reach for it).

However, there are alternative reasons why a child may not search for an object rather than a lack of understanding of the situation.

The child could become distracted or lose interest in the object and therefore lack the motivation to search for it, or simply may not have the physical coordination to carry out the motor movements necessary for the retrieval of the object (Mehler & Dupoux, 1994).

The A-not-B Error

When presented with two possible locations, the A-not-B error occurs when infants search for a hidden toy at the incorrect location (Piaget, 1954).

The toy is repeatedly hidden at location A. After a short delay, infants are then allowed to reach for and retrieve the toy.

After a few trials, the toy is then clearly hidden in location B. After a short delay, they are then allowed to reach for the toy.

Infants 8 to 10 months of age consistently reach location A despite clearly seeing the toy hidden at location B.

Critical Evaluation

There is evidence that object permanence occurs earlier than Piaget claimed. Bower and Wishart (1972) used a lab experiment to study infants between 1 – 4 months old.

Instead of using Piaget’s blanket technique, they waited for the infant to reach for an object, then turned out the lights so that the object was no longer visible. They then filmed the infant using an infrared camera. They found that the infant continued to reach for the object for up to 90 seconds after it became invisible.

Again, just like Piaget’s study, there are also criticisms of Bower’s “reaching in the dark” findings. Each child had up to 3 minutes to complete the task and reach for the object. Within this time period, it is plausible they may have successfully completed the task by accident.

For example, randomly reaching out and finding the object or even reaching out due to the distress of the lights going out (rather than reaching out with the intention of searching for an object).

Violation of Expectation Research

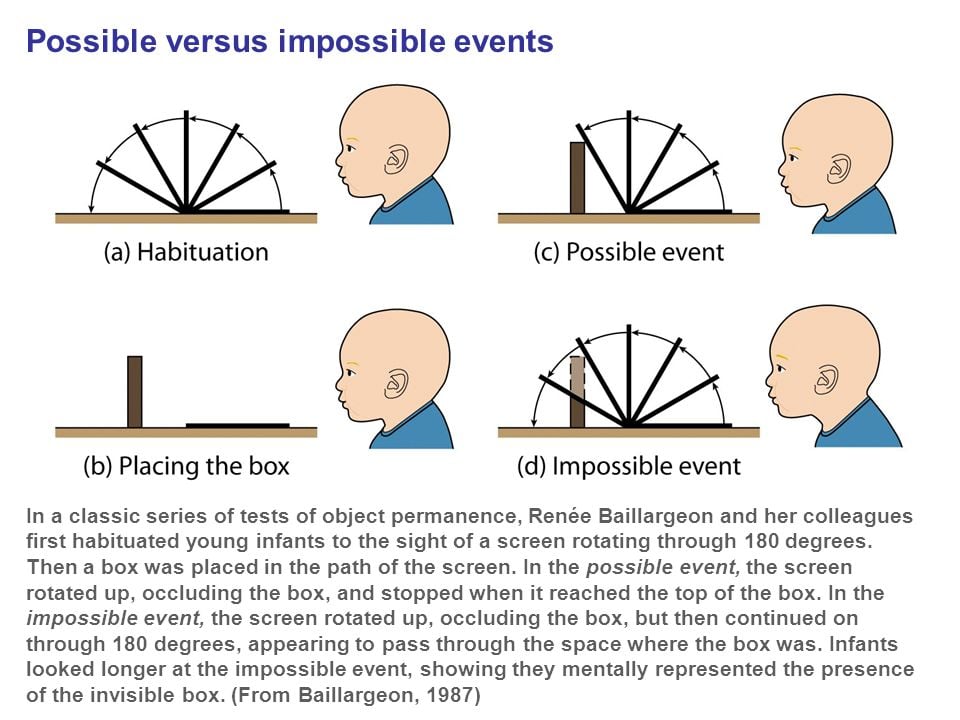

A further challenge to Piaget’s claims comes from a series of studies designed by Renee Baillargeon. She used a technique that has come to be known as the violation of expectation (VOE) paradigm.

It exploits the fact that infants tend to look for longer at things they have not encountered before.

In a VOE experiment, an infant is first introduced to a novel situation. They are repeatedly shown this stimulus until they indicate, by looking away, that it is no longer new to them. In Baillargeon et al.’s (1985, 1987) study, the habituation stimulus was a ‘drawbridge’ that moved through 180 degrees.

The infants are then shown two new stimuli, each variation on the habituation stimulus.

In Baillargeon’s experiments, one of these test stimuli is a possible event (i.e., one which could physically happen), and the other is an impossible event (i.e., one that could not physically happen in the way it appears).

In the ‘drawbridge’ study, a colored box was placed in the path of the drawbridge. In the possible event, the drawbridge stopped at the point where its path would be blocked by the box. In the impossible event, the drawbridge appeared to pass through the box and ended up lying flat, and the box apparently disappeared.

Baillargeon found that infants spent much longer looking at the impossible event. She concluded that this indicated surprise on the infants’ part and that the infants were surprised because they had expectations about the behavior of physical objects that the impossible event had violated.

In other words, the infants knew that the box still existed behind the drawbridge and, furthermore, that they knew that one solid object could not just pass through another. The infants in this study were five months old, at which Piaget would say that such knowledge is beyond them.

Critical Evaluation

Many studies suggest infants as young as 2.5 months can represent hidden objects, using a violation-of-expectation (VOE) method. In VOE studies, longer looking at an unexpected versus expected event provides evidence infants have an expectation, detect its violation, and are surprised (Baillargeon & Luo, 2002).

However, some have proposed “transient preference” accounts questioning these interpretations (Bogartz, Shinskey & Schilling, 2000; Thelen & Smith, 1994). These suggest familiarization trials create superficial preferences for unexpected events absent real expectations.

For example, infants may build event sequence predictions that unexpected events disrupt, or attend only to novel elements in unexpected events due to limited processing, or prefer events resembling unfinished familiarization processing.

The debate centers on whether young infants truly represent hidden objects or just show transient preferences in VOE tasks. Resolving this has implications for understanding cognitive development in infancy.

Adaptive Process View

There is a debate about when infants achieve “object permanence” – knowing objects still exist when out of sight. In some tasks, even young infants show expectations suggesting they understand object permanence. Yet in other tasks, infants don’t retrieve hidden objects until around 8 months.

The traditional view is that early successes reflect having the object permanence concept, while failures reflect deficits in abilities to act on this knowledge.

An alternative “adaptive process” view sees infants’ knowledge as graded, embedded in behavior-generating mechanisms, and gradually strengthened with experience. On this view, different behaviors place differing demands on emerging knowledge representations.

The adaptive process view proposes that infants’ knowledge is graded rather than all-or-none (Munakata et al., 1997). Knowledge exists on a continuum that gradually strengthens over time through repeated experiences. This knowledge is embedded within the neural mechanisms that generate observable behaviors (Thelen & Smith, 1994), rather than taking the form of abstract, explicit principles.

The adaptive process view proposes that infants’ knowledge is:

- Graded – Knowledge is not all-or-none. Instead, there are degrees of knowledge that strengthen gradually over time.

- Embedded – Knowledge is embedded within the mechanisms and neural systems that generate observable behavior. It does not take the form of abstract, explicit principles.

- Strengthened through experience – As infants accumulate experiences, the connections between relevant neurons are gradually strengthened. This serves to solidify internal representations of concepts like object permanence.

As infants accumulate experiences, the connections between relevant neurons are gradually strengthened. This serves to solidify internal representations of concepts like object permanence (Munakata et al., 1997).

Different behaviors make different demands on the knowledge representations that are currently available (Smith & Thelen, 1993).

For example, merely looking at an event relies only on weakly activated representations, whereas reaching for hidden objects requires stronger representations that can overcome conflicting perceptual information (Munakata et al., 1997).

Therefore, failures on some tasks do not necessarily indicate a complete lack of knowledge. Rather, success or failure is dependent on whether the existing state of knowledge representations is sufficient to drive that specific behavior in that specific context (Fischer & Bidell, 1991).

Over time, as connections strengthen through repeated experiences, behavior becomes increasingly flexible as infants become able to succeed across more varying situations and tasks.

Knowledge thus emerges gradually from the dynamics of neural systems adapting to make sense of the environment (Thelen & Smith, 1994).

Help Your Child Develop Object Permanence

Rather than an all-or-none achievement, research suggests object permanence emerges gradually as a progression of knowledge and skills from reflexes to representation.

Caregivers can promote development through play allowing intention, cause-and-effect reasoning, and representational abilities to unfold.

Playing interactive games that involve temporarily hiding and revealing toys is an excellent way to help your child learn that objects still exist when out of sight. Here are some easy activities:

- Play Peekaboo. Cover your face or hide a toy behind your hands, then reveal. Ask, “Where’s the toy?” before showing it again. This teaches object permanence skills.

- Hide Toys. Hide your child’s favorite toy under blankets or behind furniture. Encourage them to search for the hidden object, then celebrate when they find it. Retrieving hidden items promotes the understanding that unseen toys still exist.

- Read Hide & Seek Books. Books featuring lift-the-flap activities allow your child to actively engage with finding hidden objects on the page. Choose sturdy board books they can handle.

- Play Hunting Games. Have your child close their eyes while you hide a toy. Give warm praise when they successfully locate and retrieve the toy you hid. This makes learning object permanence concepts fun!

Playing interactive hiding games provides natural opportunities to develop your child’s understanding that objects continue existing separately from their own perception. Have fun promoting this key cognitive skill!

References

Aguiar, A. & Biallargeon, R. (1999). 2.5-Month-Old Infants’ Reasoning About When Objects Should

and Should Not Be Occluded. Cognitive Psychology, 39, 116-157.

Baillargeon, R. (1987). Object permanence in 3½-and 4½-month-old infants. Developmental psychology, 23(5), 655.

Baillageon, R. (2004). Infants’ Reasoning About Hidden Objects: Evidence for Event-General and

Event-Specific Expectations. Developmental Science, 7, 391-414.

Baillargeon, R, & Graber, M. (1987). Where’s the Rabbit? 5.5-Month-Old Infants’ Representations of

the Height of a Hidden Object. Cognitive Development, 2, 375-392.

Baillargeon, R., & Luo, Y. (2002). Development of the object concept (Vol. 3). Encyclopedia of cognitive science, London: Nature, pp. 387–391.

Baillargeon, R., Spelke, E. S. & Wasserman, S. (1985). Object Permanence in Five-Month-Old Infants. Cognition, 20, 191-208.

Bower, T.G.R. (1967). The Development of Object Permanence: Some Studies of Existence Constancy. Perception & Psychophysics, 2, 411-418.

Bogartz, R. S., Shinskey, J. L., & Speaker, C. J. (1997). Interpreting infant looking: The Event Set £ Event Set

design. Developmental Psychology, 33, 408–422.

Bower, T. G. R., & Wishart, J. G. (1972). The effects of motor skill on object permanence. Cognition, 1, 165–172.

Diamond, A. (1985). Development of the ability to use recall to guide action, as indicated by infants’ performance on AB. Child development, 868-883.

Fischer, K. W., & Bidell, T. (1991). Constraining nativist inferences about cognitive capacities. In S. Carey & R. Gelman (Eds.), The epigenesis of mind (pp. 199-236). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Mehler, J., & Dupoux, E. (1994). What Infants Know: The New Cognitive Science of Early Development. Blackwell Publishers.

Munakata, Y., McClelland, J. L., Johnson, M. H., & Siegler, R. S. (1997). Rethinking infant knowledge: Toward an adaptive process account of successes and failures in object permanence tasks. Psychological Review, 104(4), 686–713.

Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: Basic Books.

Piaget, J. (1963). The Psychology of Intelligence. Totowa, New Jersey: Littlefield Adams.

Smith, L. B., & Thelen, E. (Eds.). (1993). A dynamic systems approach to development: Applications. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Thelen, E., & Smith, L. B. (1994). A dynamic systems approach to the development of cognition and action. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wang, S-h., Baillargeon, R. & Brueckner, L. (2004). Young Infants’ Reasoning About Hidden Objects:

Evidence from Violation of Expectation Tasks with Test Trials Only. Cognition, 23, 167-198.