The id, first conceived of by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1923), is the part of the personality that is driven by instinctual needs and desires.

The id is the primary source of motivation for all human behavior, namely basic needs, such as hunger, emotional expression, and sex.

The id operates on the pleasure principle, which means that it seeks to gratify its needs and desires in any way possible.

Overview and History

In psychoanalytic theory, the id is the component of the personality that contains the instinctual, biological drives that supply the psyche with its basic energy or libido.

The psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud conceived of the id as the most primitive component of the personality, located in the deepest level of the unconscious.

It has no inner organization and operates in obedience to the so-called pleasure principle — a desire for gratification and avoiding or dissipating pain.

Thus, the infant’s life is dominated by the desire for immediate gratification of instincts, such as hunger and sex.

This id dominance remains until the next level of personality, the ego, begins to develop and operate in accordance with reality.

Freud’s tripartite theory has had a profound influence on psychology, particularly in the area of human development.

Freud believed that the id was responsible for all of our basic needs and drives, including sex, hunger, and aggression.

Freud believed that the id was constantly trying to satisfy these drives but was often frustrated by the reality principle, which dictated that we could not always have what we wanted.

This frustration often leads to conflict within the personality, which could manifest itself in various ways, such as anxiety or neurosis (Freud, 1923).

While Freud’s theory of the id has been criticized by many psychologists over the years, it continues to be one of the most influential theories in psychology.

It has helped psychologists to understand the role of people’s basic drives in human behavior and has provided a framework for understanding how people resolve conflict within themselves.

When Does the Id Emerge?

Freud considered personality to be similar to an iceberg. He believed that the ego, or conscious mind, was just the tip of the iceberg, while the rest of personality was submerged in the unconscious.

The id is, in this view, the deepest level of personality, located in the unconscious mind. It operated according to the pleasure principle, which meant that it was always seeking immediate gratification.

The id is, according to Freud, a primitive part of personality and contains basic drives, such as sex and aggression.

Freud believed that these drives were innate and would emerge even if people were not socialized or taught about them.

For example, he believed that infants are born with sexual urges, even though they may not yet be aware of what sex is.

The id was also responsible for many of our primitive impulses, such as hunger and thirst. Freud believed that these drives were so powerful that they could not be controlled by the ego.

For example, if someone experiences hunger, the thought of eating dominates their mind, leading them to not be able to think about anything else.

The id would always seek to satisfy these drives, regardless of whether or not it was realistic or possible.

The Id and Personality

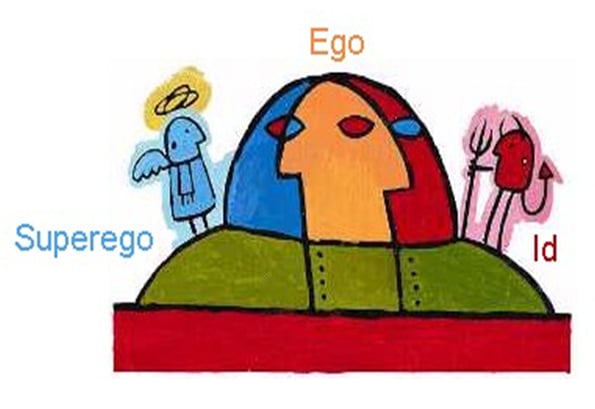

While the id is present from birth, Freud (1923) believed that it was not the only component of personality. He proposed that the ego and superego, two other parts of personality, emerge as a child grows and matures.

The ego develops in response to the demands of reality. It begins to form around the age of two and helps the individual deal with the outside world in a more realistic way.

For example, the ego prevents an infant from biting people when they are frustrated, as this would lead to negative consequences. The ego is also responsible for organizing our thoughts and decision-making.

The superego is the last part of the personality to develop and usually emerges around the age of five or six. It is the part of personality that internalizes the values and morals of society.

The superego is often in conflict with the id, as it seeks to control our primitive impulses. For example, the superego would tell us not to steal, even if we really wanted to.

The id, ego, and superego all play an important role in human behavior. Together, they help us to understand both our conscious and unconscious motivations (Erwin, 2002).

How the Id Operates

The id motivates you to seek pleasure whilst avoiding pain and do so at whatever cost to others; it is entirely selfish.

The Id operates on what Freud called the Pleasure Principle and is present at birth.

The Id, in turn, is driven by two other instinctive drives:

Eros or life instinct: which gets its energy from the libido. Eros drives us to behave in life-preserving and life-enhancing ways, to avoid danger, to keep warm and well-fed, and to reproduce.

Thanatos: or death instinct, which will cause us to attack anyone that gets in the way of satisfying the libido. Thanatos, however, can be destructive when turned inwards.

The id relies on the primary process to temporarily relieve the tension caused by a need that cannot be immediately met.

The primary process involves forming a mental image of the desired object and then satisfying the need with this image.

This can be seen in daydreaming, which allows us to temporarily escape from reality and satisfy our needs.

For example, if someone is hungry, the id will create a mental image of food, and then satisfaction will come from eating the food in our imagination.

Similarly, if someone is sexually frustrated, the id may create a mental image of a sexual encounter, and then satisfaction will come from fantasizing about this encounter.

The id is not concerned with reality, only with satisfying its needs. This can often lead to problems, as the things that someone wants are not always possible or realistic.

For example, an athlete may want to win a gold medal, but this may not be possible. The athlete’s id would then keep repeating the desire for a gold medal, leading to frustration and disappointment.

The id can also cause problems in relationships, as it may lead us to act impulsively and without thinking about the consequences.

For example, someone who is angry may lash out at their partner in an attempt to relieve emotional tension without considering how this would hurt them.

Id Defense Mechanisms

The id is often responsible for defense mechanisms, which are unconscious strategies that someone uses to protect themselves from anxiety.

As the id demands instant gratification, there is conflict with the superego’s sense of right and wrong.

Therefore, the ego must step in to be the referee between the two to restore them to reality. This causes much anxiety, and the Ego defends itself against this by using defense mechanisms that reduce the anxiety.

Defense mechanisms allow people to cope with the demands of reality and the outside world (Brenner, 1981).

Common defense mechanisms include denial, repression, and projection. Denial is when someone refuses to accept that something is true, even though it may be obvious.

For example, someone who is facing a terminal illness may deny their diagnosis to avoid the pain and anxiety that comes with it.

Repression is when someone pushes painful memories or thoughts out of our conscious awareness.

For example, someone who was sexually abused as a child may repress these memories as a way of dealing with the pain. Projection is when someone attributes their own thoughts and feelings to others (Brenner, 1981).

Examples

Thirst and hunger

The id is concerned with meeting basic needs, such as satiating hunger and thirst.

Seeking instant gratification, the id can cause people to become tense, anxious, or angry when these needs are not met.

Some examples of the id dominating someone’s sense of thirst and hunger can include (Erwin, 2002):

-

Rather than waiting for the server to refill someone’s glass of water, they reach across the table and drink someone else’s.

-

A hungry baby crying until they are fed.

-

A toddler whining incessantly until given another sweet.

-

In line at the grocery store, someone is so hungry that they take a bite out of their sandwich as they wait for the line to move.

Rage

Rage is a strong emotion that is often explained by Freud’s id.

When someone experiences rage, it is typically in response to feeling frustrated, threatened, or helpless.

For example, someone may feel rage when they are stuck in traffic or when someone cuts them off in line.

Nonetheless, rage can be an adaptive emotion that helps people to survive and protect themselves. For example, if someone is being attacked by another, the rage may give them the strength to fight back and defend themselves.

However, rage can also be destructive and lead to problems such as violence and aggression (Erwin, 2002).

When the id is in control, people may act impulsively and without thinking about the consequences of their actions. This can lead to problems such as:

- An enraged driver pulled his car onto the shoulder of a road and sped forward, not caring that he was clipping people’s side mirrors as he tried to get ahead of the cars in front of him.

- A child throwing a toy across a room to express his anger.

- A husband making a personal attack on his wife in an attempt to cover up the root causes of his resentment.

References

Brenner, C. (1981). Defense and defense mechanisms. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 50(4), 557-569.

Erwin, E. (2002). The Freud encyclopedia: Theory, therapy, and culture. Taylor & Francis.

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle. SE, 18: 1-64.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. SE, 19: 1-66.