| Bourgeoisie | Proletariat | |

|---|---|---|

| Class position | Owns means of production | Works for wages |

| Means of production | Owns factories, land, infrastructure | Operates means of production they don’t own |

| Income source | Profits, investments, rents | Wages, salaries |

| Wealth | Accumulates capital | No capital, lives paycheck to paycheck |

| Political power | Dominant class with great influence | Minimal influence as individuals |

| Lifestyle | Comfortable, even extravagant living | Bare subsistence level living |

| Typical jobs | Factory owners, bankers, executives | Factory workers, clerks, service workers |

| Education | Quality schools, often highly educated | Lower quality public schools, less education |

| Values | Uphold status quo, individual achievement | Seek social change, collective interests |

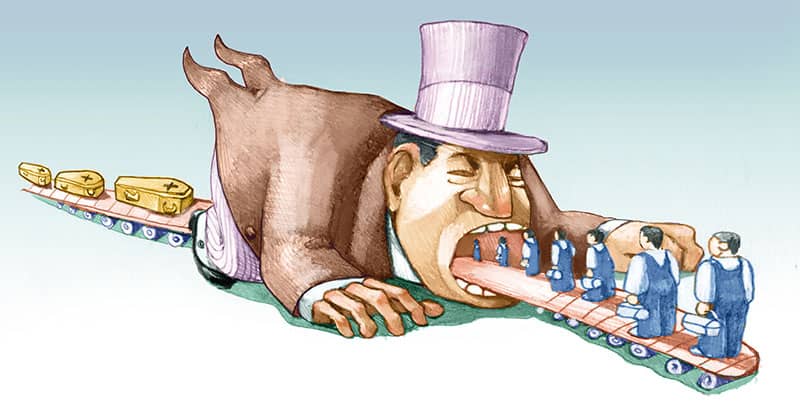

According to Karl Marx, the bourgeoisie, also known as the capitalist or ruling class, are those who own the means of production and monopolize wealth, and stand in contrast to the working-class proletariat majority, whose labor-power is exploited by the bourgeoisie majority.

According to Marx, the workers are those from a low social class, which he termed the proletariat, whereas those few in charge, the wealthy bosses, owners, and managers, are what he termed the bourgeoisie.

The proletariat are the individuals who perform labor that is then taken and sold by the bourgeoisie so that they themselves receive profit while the workers receive minimal wages.

Noteworthy writings of Marxism include Capital by Marx and The Communist Manifesto written by Marx and Friedrich Engels. These writings describe the features of Marxist ideology, including the struggle of the working class, capitalism, and how a classless society is needed to end the class conflict.

The Bourgeoisie

The term bourgeoisie is one that dates back centuries, but rose to prominence with Marx”s concept of the class struggle. In Marxism, the term bourgeoisie refers to a social order dominated by the ruling or capitalist class, those who own property and, thus, the means of production.

According to Marx, the bourgeoisie is the ruling class in capitalist societies. That is, economic power gives access to political power and cultural influence.

The bourgeoisie, sometimes called the capitalists, own the means of production. They are the owners of capital and are able to acquire the means of creating goods and services, such as natural resources, or machinery.

With their capital, the bourgeoisie can purchase and exploit labor power, using the surplus value that their employees generate to accumulate or expand their capital (Wolf & Resnick, 2013).

The key differentiation between the bourgeoisie and other social elites is this ownership of the means of production.

Managers of the state or landlords, for example, are not part of the bourgeoisie because capitalists must be actively involved in capital accumulation by using money to organize the means of production and employ and exploit labor to further generate capital.

Marx believed that the bourgeoisie began in medieval Europe with traders, merchants, craftspeople, industrialists, manufacturers, and so on who could increase wealth through industry. These individuals employed labor to create capital (Wolf & Resnick, 2013).

Petty Bourgeoisie

Petty bourgeoisie is a term derived from French, often employed to pejoratively describe a social class comprising small-size merchants and semi-autonomous peasants whose ideological position during socioeconomic stability reflects the high bourgeoisie whose morality it endeavors to emulate.

The term, petty bourgeoisie, has been used by various Marxist theorists (including Marx himself) to denote the ranks of the bourgeoisie comprising those sandwiched between the supposedly wealthy owners of the means of production and the oppressed proletariat.

In Marx’s categorization of social classes, the petty bourgeoisie are self-employed, or those who employ a few laborers in their economic activity.

These are associated with the shop-keeping or independent artisan class, who form a buffer between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

The Proletariat

The second major class in Marxism is the proletariat, who own their labor, but none of the means of production. Because these workers have no property, they must find employment in order to survive and obtain an income.

The proletariat are a class of people who, in the view of Marx, compose the majority of society. They sell their ability to do work and their labor in order to survive.

Engels illustrated the image of the proletariat as a class in his study of the working class in Manchester in 1833, which happened concurrently with Marx”s discovery of the proletariat on the streets of Paris. Proletarians literally have nothing to sell but their labor power.

Unlike the bourgeoisie, the proletariat does not own the means of production. Karl Marx considered this dynamic to be one of exploitation, where the Bourgeoisie absorbs the value of the goods and services that the proletariat produce without paying this value back to them.

In a capitalist society, the proletariat are legally free and separated from the means of production. The proletariat do not receive the value of their goods that their labour produces, but only the cost of subsistence.

The exploitation of the proletariat by the capitalist, however, means that the proletariat is unable to earn enough to acquire his own means of production.

Because he does not own the means of production, he does not have all of the factors of production. This keeps him in a continual cycle of exploitation by capitalists (Wolf & Resnick, 2013).

Being confined to a component means that workers lose value and are potentially less skilled when seeking other employment (Chiapello, 2013).

Proletariat Revolution

Marxists see capitalism as an unstable system that will eventually result in a series of crises. The more that capitalism grows, the more people take advantage of it, and the more oppressed, degraded, and exploited the proletariat will be (Marx, 1873).

Eventually, capitalism will result in a revolt by the proletariat, according to Marxists. This will lead to the dismantling of capitalism to make way for a socialist or communist state.

In the Communist Manifesto, written in 1848, Marx and Engels proposed that the proletariat revolution was inevitable and would be caused by the continued exploitation of the capitalists. The workers will eventually revolt due to increasingly worse working conditions and low wages.

Marx argued that a social revolution would mean changing the existing social and political system from a capitalist to a communist society. A communist society means there are no social classes or private property.

The result of the revolution is that capitalism will be replaced by a classless society in which private property will be replaced with collective ownership. This will mean that society will become communist.

References

Callinicos, A. (2003). Anti-capitalist manifesto. Polity.

Chiapello, E. (2013). Capitalism and its criticisms. New spirits of capitalism? Crises, justifications, and dynamics, 60-81.

Jahan, S., & Mahmud, A. S. (2015). What is capitalism. International Monetary Fund, 52(2), 44-45.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1967). The communist manifesto . 1848. Trans. Samuel Moore. London: Penguin, 15.

Mueller, D. C. (Ed.). (2012). The Oxford handbook of capitalism. Oxford University Press.

Rand, A. (1967). What is capitalism? (pp. 11-34). Second Renaissance Book Service.

Sagarra, E. (2017). The bourgeoisie. In A Social History of Germany 1648-1914 (pp. 253-262). Routledge.

Siegrist, E. (2007). Bourgeoisie, History of. in Ritzer, G. (Ed.). Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology.

Stern, B. J. (1948). Engels on the Family. Science & Society, 42-64.

Resnick, S. A., & Wolff, R. D. (2013). Marxism. Rethinking Marxism, 25(2), 152-162.

Weber, M. (1921). The City.

Weber, M. (1930). The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. New York, NY: Charles Scribner”s Sons (reprint 1958).

Weber, M. (1936). Social actions.