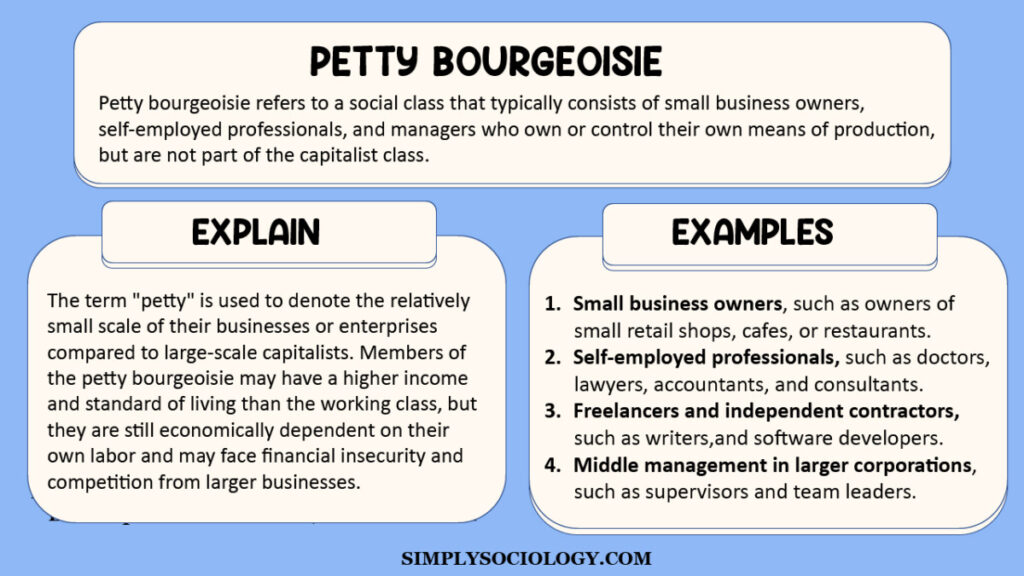

The petty bourgeoisie, or petit bourgeoisie, in sociology refers to a social class between the working class and the middle class, often including small business owners, managers, salespeople, independent professionals, and other workers who may own means of production but do not employ a substantial workforce. As they share aspects of both classes, they typically lack a cohesive identity and clear economic interests as a class, leading to fluctuating political alliances.

Key Takeaways

- Petty bourgeoisie is a term derived from French, often employed to pejoratively describe a social class comprising small-size merchants and semi-autonomous peasants whose ideological position during socioeconomic stability reflects the high bourgeoisie whose morality it endeavors to emulate.

- The term has been used by various Marxist theorists (including Marx himself) to denote the ranks of the bourgeoisie comprising those sandwiched between the supposedly wealthy owners of the means of production and the oppressed proletariat.

Examples

Following are some examples of those who could be described as the petty bourgeoisie:

-

Traders

-

Merchants

-

Some land-owning farmers

-

Independent artisans

-

Small-scale shopkeepers

The Petty Bourgeoisie in Marxism

In Marx’s categorization of social classes, the petty bourgeoisie are self-employed, or those who employ a few laborers in their economic activity. These are associated with the shop-keeping or independent artisan class, who form a buffer between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

Because of their intermediary position, they were seen as being pulled in both directions, sometimes taking a revolutionary role and sometimes a conservative stance on the political questions of daily life. They were thus economically determined, but ideologically and politically fluid.

The petty bourgeoisie has been historically viewed as partakers of the systems of private property which undergird capitalist societies (Poulantzas, 1979). However, they lack enough capital to benefit from workforce rationalization and massive-scale industrialization.

On the other hand, they do not have to rely on selling their labor, and may even employ other people. Unlike capitalists, however, the petty bourgeoisie has to work and may do so alongside their family members as well as their employees.

Karl Marx claimed that during France’s failed revolution in 1848, the petty bourgeoisie had shifted their loyalty to the bourgeoisie from the proletariat (Poulantzas, 1979).

The mid-1840s had seen the petty bourgeoisie, amidst widespread discontent and famine, fighting alongside students and the urban proletariat, demanding liberal reforms and the recognition of supposed workers’ rights.

However, the conflict evolved into anarchic upheaval, and consequently, the petty bourgeoisie ended up transferring their allegiance to the counter-revolutionary movement comprising the conservative peasantry, the bourgeoisie, and powerful feudal remnants.

The upshot was the establishment of the Second Republic of France having as its president Napoleon III, who would go on to become the Emperor of France.

Friedrich Engels, on the other hand, was more inclined to see the petty bourgeoisie as a transitional middle class rather than a stationary middle class (Poulantzas, 1979).

He had identified this transitional type of middle class as a section sandwiched between the nobility it had surpassed, and the working class it would be eventually displaced by.

The Petty Bourgeoisie Overtime

The late 20th century saw a decrease in the term’s usage, accompanied by more frequent references to the middle class (Poulantzas, 1979).

Somewhat disassociated from the bourgeoisie, the term middle class, has come to mean a subsection of society whose valorization and expansion could increase upward mobility, spur economic growth, and advance democratization.

Different theorists have attempted to distinguish the petty bourgeoisie from both the proletariat and the bourgeoisie by arguing that their mental labor was hostile to the interests of the working class (Poulantzis, 1975).

The petty bourgeoisie was seen as representing capitalist interests without necessarily owning capital in a way they could alienate it. The plenitude of joint-stock companies affords an example of this evolution that defies theorization and hinders radical political organization (Wright, 1978).

In the meantime, images of small business owners freed from the demands to toil for others continue to occupy the popular imagination. The norms of individual freedom, personal autonomy, and entrepreneurship exert a potent influence on many.

Thus, this new middle class, or the latest petty bourgeoisie seems to enormously shape the economic trajectory of today’s society.

Further Information

References

Bernstein, H. (1988). Capitalism and petty‐bourgeois production: Class relations and divisions of labour. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 15(2), 258-271.

Marx, K. (1968). The Class Struggles in France: 1848-1850. Wellred Books.

Marx, K. (1926). The eighteenth brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. International Publishers.

Poulantzis, N. (1975). Social Classes in Contemporary Capitalism. London: New Left Books.

Poulantzas, N. (1979). The new petty bourgeoisie. Insurgent Sociologist, 9(1), 56-60.

Wright, Olin E. (1978). Class, Crisis and the State. London: New Left Books.