A retrospective study, sometimes called a historical cohort study, is a type of longitudinal study in which researchers look back to a certain point to analyze a particular group of subjects who have already experienced an outcome of interest.

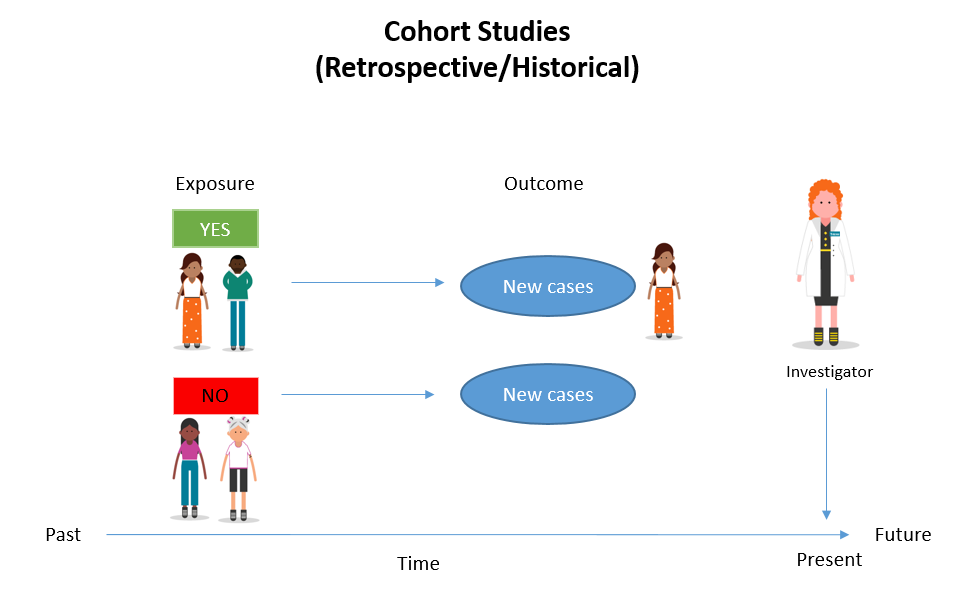

In a retrospective cohort study, the researcher identifies a group of individuals who have been exposed to a certain factor and a group who have not been exposed (the cohorts), and then looks back in time to see how the rate of a certain outcome (like the development of a disease) differs between the two groups.

For example, a researcher might identify a group of people who smoked and a group who never smoked, and then look back at medical records to see how the rate of lung cancer differs between the two groups.

This type of study is beneficial for medical researchers, specifically in epidemiology, as scientists can use existing data to understand potential risk factors or causes of disease.

How to Use

Researchers in retrospective studies will identify a cohort of subjects before they have developed a disease and then use existing data, such as medical records, to discover any patterns and examine exposures to suspected risks.

In cohort studies, one group of participants must share a common exposure factor, and this group is compared to another group of participants who do not share the exposure to that factor.

For example, men over age 60 who exercise daily could be compared to men over age 60 who do not exercise daily (control) to study the prevalence of diabetes in men over 60.

Researchers collect data from existing records to study a relationship and determine the influence of a particular factor (i.e., daily exercise) on a particular outcome (i.e., diabetes) and to analyze the relative risk of the cohort compared to the control group.

Advantages

Feasibility

Estimating the relative risk of a population tends to be easier with retrospective studies than prospective studies. Retrospective studies are conducted on a smaller scale than prospective studies.

Because researchers study groups of people before they develop an illness, they can discover potential cause-and-effect relationships between certain behaviors and the development of a disease.

Inexpensive and less time-consuming

Retrospective studies tend to be cheaper and quicker than prospective studies as the data already exists, and researchers do not need to recruit participants.

Beneficial for rare diseases

Researchers in retrospective studies can address rare diseases easier than in prospective studies because, in prospective studies, researchers would need to recruit extremely large cohorts.

Limitations

Bias and confounding variables

Most sources of error in retrospective studies are due to confounding and bias. These errors are more common in retrospective studies than in prospective studies, so a retrospective study design should not be used when a prospective design is possible.

Recall bias

Participants might not be able to remember if they were exposed or when they were exposed, or they might omit other details that are important for the study.

Missing data

Because researchers are using already existing data, they rely on others for accurate recordkeeping, and important information may not have been collected in the first place.

Examples

- Investigation of risk factors for breast cancer (Press & Pharoah, 2010).

- Characteristics of trafficked adults and children with severe mental illness (Oram et al., 2015).

- Activated injectable vitamin D and hemodialysis survival (Teng et al., 2005).

- Reporting critical incidents in a tertiary hospital Munting et al., 2015).

- Reporting critical incidents in a tertiary hospital (Munting et al., 2015).

- Association between blood eosinophil count and risk of readmission for patients with asthma (Kerkhof et al., 2018).

- Risk factors for mental disorders in women survivors of human trafficking (Abas et al., 2013).

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the difference between case-control and retrospective cohort studies?

Case-control studies are usually, but not exclusively, retrospective. Case-control studies are performed on individuals who already have a disease, and researchers compare them with other individuals who share similar characteristics but do not have the disease.

In a retrospective cohort study, on the other hand, researchers examine a group before any of the subjects have developed the disease. Then they examine any factors that differed between the individuals who developed the condition and those who did not.

More simply, the outcome is measured before the exposure in case-control studies, whereas the outcome is measured after exposure in cohort studies.

2. Is a retrospective study experimental?

No, retrospective cohort studies are observational. Researchers analyze a group of subjects without manipulating any variables or interfering with their environment.

Researchers use existing data to investigate the target population, so no experimentation is necessary. Retrospective cohort studies examine cause-and-effect relationships between a disease and an outcome. However, they do not explain why the factors that affect these relationships exist.

Experimental studies are required to determine why a certain factor is associated with a particular outcome.

References

Abas, M., Ostrovschi, N.V., Prince, M, et al. (2013). Risk factors for mental disorders in women survivors of human trafficking: a historical cohort study. BMC Psychiatry 13, 204. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-204.

Hess, D.R. (2004) Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respir Care. 49(10):1171-4. PMID: 15447798.

Kerkhof, M., Tran, T.N., Van den Berge, M., Brusselle, G.G., Gopalan, G., Jones, R.C.M., et al. (2018). Association between blood eosinophil count and risk of readmission for patients with asthma: Historical cohort study. 13(7): e0201143.

Munting, K.E, et al. (2015). Reporting critical incidents in a tertiary hospital: a historical cohort study of 110,310 procedures. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 62, 1248–1258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-015-0492-y

Oram, S., Khondoker, M.R., Abas, M.A., Broadbent, M.T., & Howard, L.M. (2015). Characteristics of trafficked adults and children with severe mental illness: a historical cohort study. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 2 12, 1084-91.

Press, D. J., & Pharoah, P. (2010). Risk factors for breast cancer: a reanalysis of two case-control studies from 1926 and 1931. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.), 21(4), 566–572. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e08eb3

Ranganathan, P., & Aggarwal, R. (2018). Study designs: Part 1 – An overview and classification. Perspectives in clinical research, 9(4), 184–186.

Song, J. W., & Chung, K. C. (2010). Observational studies: cohort and case-control studies. Plastic and reconstructive surgery, 126(6), 2234–2242. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f44abc.

Teng, M., Wolf, M., Ofsthun, M. N., Lazarus, J. M., Hernán, M. A., Camargo, C. A., Jr, & Thadhani, R. (2005). Activated injectable vitamin D and hemodialysis survival: a historical cohort study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN, 16(4), 1115–1125.

Further Information

- Cohort Effect? Definition and Examples

- Barrett, D., & Noble, H. (2019). What are cohort studies?. Evidence-based nursing, 22(4), 95-96.

- Hess, D. R. (2004). Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respiratory care, 49(10), 1171-1174.

- Euser, A. M., Zoccali, C., Jager, K. J., & Dekker, F. W. (2009). Cohort studies: prospective versus retrospective. Nephron Clinical Practice, 113(3), c214-c217.