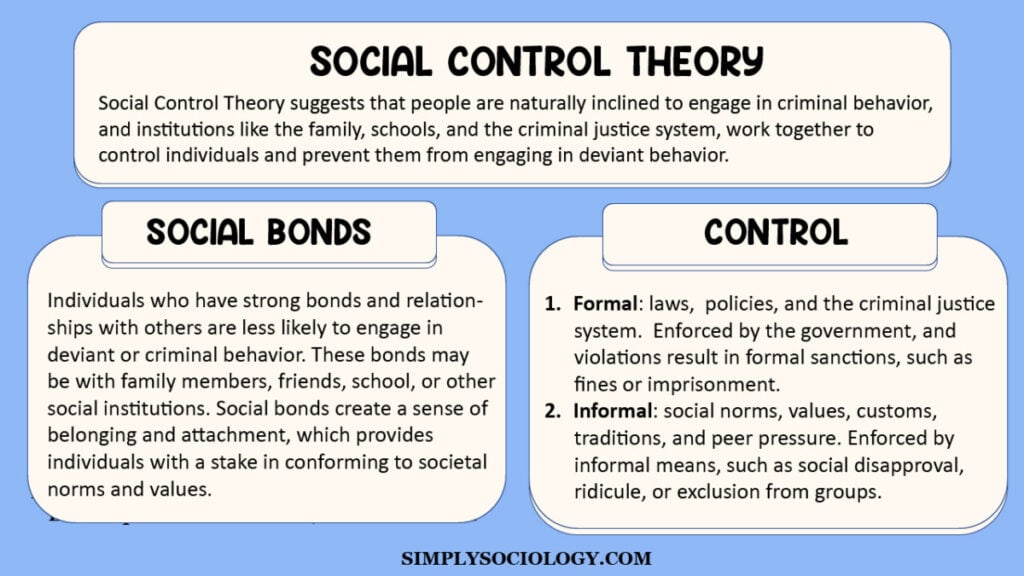

Social control is the process whereby society seeks to ensure conformity to the dominant values and norms in that society. This process can be either informal, as in the exercise of control through customs, norms, and expectations, or formal, as in the exercise of control through laws or other official regulations.

The tactics adopted to establish social control may include a mixture of negative sanctions, which punish those who transgress the rules of society, and positive policies which seek to persuade or encourage voluntary compliance with society”s standards.

Albion Woodbury Small and George Edgar Vincent introduced the concept of social control to sociology in 1894. However, this introduction had been foreshadowed in Thomas Hobbes’ discussion of the state.

Much later, Talcott Parsons (1937) and Travis Hirschi (1969) played a vital role in the illumination and development of ‘social control.’

While deviance, the antithesis of social control, investigates into reasons actuating rebellion against accepted norms, social control seeks to explain people’s conformity to the same. Its chief objective is to maintain order and peace in society.

Agencies of Social Control

Agents of social control are the people or groups who work to influence or regulate the behavior of others. They can be found in all levels of society, from the family to the government.

- Education: The inculcation of civic norms, which transpires at a tender age for most children, is often inspired by the desire of those in authority to ensure that the future citizens would remain committed to upholding that particular society’s abiding values . The recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance, and elementary school courses on democracy exemplify this.

- Family: The control exerted on individuals by their parents, siblings, spouses, and relatives seldom employs clear rules. However, children learn how to respect authority from their parents. Siblings may aid one in discerning early the appropriate standards for acceptable behavior among one’s peers.

- Community:Implicit threats of ridicule, shame, and ostracization pervade most mechanisms of social control employed by various communities. The prospect of exclusion from a house of worship may procure and preserve a religious group’s members’ fidelity to orthodox beliefs. Likewise, the hope of reward (extratemporal bliss, or even human respect) may inspire members to assist each other in times of need.

- Criminal Justice System:Severe punishments meted out to convicted criminals may serve to deter future felonies. The temporary removal of wrongdoers from society at large both impedes their recruitment of others into crime and renders them incapable of committing endless infractions with impunity. Cities with higher incarceration rates, thus, are likely to have lower crime rates (Sampson, 1986).

Types of Social Control

Formal and Informal Social Control

Formal social control involves the promulgation of codified laws embodying values, and the enforcement of external sanctions by the government in order to prevent chaos in society.

Prohibitions of robbery and murder are striking examples. Perpetration of such crimes would likely produce harsh consequences such as prolonged imprisonment.

Even lesser infractions of the law, such as exceeding speed limits, generally result in significant penalties such as fines. These function to procure people’s compliance with the law of the land.

Informal social control refers to the internalization of normative mores through either unconscious or conscious socialization. The special respect accorded to the elderly, a salient characteristic of many Asian cultures, is a manifest example.

Moreover, in many free societies, the virtue of patriotism is inculcated in mostly informal ways. The United States, for instance, has no law coercing its citizens to salute their flag or recite the Pledge of Allegiance. However, the devotion wherewith many Americans engage in such exercises is a potent testament to the informal social control exerted by many families and religious communities in America.

Direct and Indirect Social Control

Karl Mannheim has categorized social control into direct and indirect forms.

Direct social control involves the direct regulation of the conduct of individuals, invariably by persons close to such individuals, or primary groups.

These persons/groups may include parents, neighbors, older siblings, grandparents, teachers, and friends.

Indirect social control involves the regulation of conduct by more distant authorities. Secondary groups, such as academic and cultural institutions may exert indirect social control via cultural taboos, public opinion, and social customs.

The influence of direct social control is more pronounced and durable than that of its indirect counterpart.

Positive and Negative Means

Kimball Young (1927) has identified and elaborated upon positive and negative social control.

Positive means of social control involve the provision of positive incentives to procure the compliance of individuals with societal norms. The promise of reward herein may range from pecuniary benefits to the public approval of conformity stemming from the internalization of various social norms.

Awards bestowed upon students for excellence in academics, titles granted to winning varsity sports teams, and honors were given to soldiers demonstrating fortitude on the battlefield are some examples.

Negative social control discourages nonconformity by penalizing deviant conduct. Incurring harsher curfews from one’s parents by violating relatively lenient ones, is an evident example.

Criticism for incompetence, mulcts for parking infractions, imprisonment for theft, and capital punishment for murder are all instances of negative social control that are designed to ensure that most people in a society would gratify its normative expectations for public peace.

Theories of Social Control

Parsons’ Approach to Social Control

Talcott Parsons was a functionalist heavily influenced by the writings of Emile Durkheim and Max Weber.

Around the 1950s, Parsons sought to align the abstract idea of social order with the concrete concept of social control by developing a theory of social systems.

This general theory identified four functions that operated through multiple levels of human reality. The analytical requisites of the functions demanded that social control be seen under four elementary types: religious, informal, medical, and legal.

Parsons inquired into how the transgenerational reproduction of societies transpires. He noted that most individuals in a society are not opposed to most societal norms and values and that they heed them for most of their lives.

He adduced socialization to explain the purported ‘willing conformity.’ In other words, socialization within families, educational institutions, and religious communities would uphold compliant members as examples meriting emulation, and aid individuals’ internalization of societal norms.

Parsons also developed a four-sub-system model applicable to the social system. The model was predicated on a social system’s tasks relevant to its milieu. The four subsystems, also known as the GAIL system, comprised the following:

-

Goal-attainment: the polity

-

Adaptation: the economy

-

Integration: the culture comprising norms concerning social control and law

-

Latency: the normative issue of incentives to gratify the social system’s requirements

While Parsons’ theorizing was not flawless, his approach incorporated the perennial problem of scarcity and its concomitant challenge of resource allocation.

Matza’s Techniques of Neutralization

David Matza and Gresham Sykes posit that conduct which undermines social norms and beliefs is accompanied by shame and guilt, which serve to dissuade many individuals from engaging in delinquency or crime (Sykes & Matza, 1957; Matza, 1964).

Consequently, would-be-delinquents contrive schemes to neutralize this guilt preemptively and safeguard their self-image, were they to partake in deviance.

For instance, they may utilize neutralizing techniques to render themselves episodic relief from normative constraints.

These mechanisms also permit delinquents to shift back and forth between criminal and conventional conduct. This drift is effectuated because the delinquents’ neutralization mechanisms significantly enfeeble the moral imperative of predominant cultural mores and counteract the guilt produced by otherwise grave transgressions.

The neutralization impedes the internal and external controls conducing to inhibiting incentives for deviance, thereby inspiring delinquency while simultaneously immunizing the perpetrators’ self-image.

Matza and Sykes focused particularly on the following five techniques of neutralization:

-

Denial of responsibility

-

Denial of victims

-

Denial of injury

-

Condemnation of condemners

-

Appeal to higher loyalties

Research on the Matza-Sykes theory has yielded mixed outcomes. Indeed, their theory of neutralization has been incorporated into other theories such as labeling theory, learning theory, and control theory.

However, its capacity to serve as a sufficient explanation of crime is yet to be established. Immo Fritsche, Shadd Maruna and Heith Copes (2005) have, in recent times, sought to summarize the state of the theory, and review its empirical evaluations in light of both psychology and sociology.

Marxist Approaches to Social Control

Marxists see the criminal justice system as part of the repressive state apparatus and used by the ruling class to maintain their power through oppression whilst appearing to be legitimate.

Laws area reflection of ruling class ideology and punishment is part of the repressive state apparatus (Althusser) which keeps people in line and in their place.

The police force and criminal justice system treat the working class and the middle class differently. Middle class are to get a slap on the wrist as they are seen as having made a mistake where are the working class are more likely to be arrested for the same crime. Also many corporate crimes are not investigated or prosecuted by the criminal justice system.

Bowles and Gintis’ Correspondence Theory underscores the purported use of education as a means by the ruling class to dictate its norms to oppressed workers. Moreover, the media, too, is viewed as engaged in gatekeeping and agenda setting to propagate the elites’ worldview.

Meanwhile, the police force is seen as an accomplice in the capitalists’ oppressive scheme, and the law enforcement’s supposed scant attention to white-collar misdemeanors such as corporate crime is cited as evidence for this purported capitalist conspiracy.

Marxist theory holds that a dominant class safeguards and promotes its economic interests via its control of criminal law as well as cultural norms.

Consequently, the normative standards, whether formal or informal, which the members of a society are expected to conform to, according to Marxism, are merely values of the ruling oppressors.

Substantial shifts in political powers, from the former oppressors to the oppressed, may present a challenge to the Marxist approach, especially if such political transitions are not accompanied by fundamental alterations in a society’s primary norms guiding individual behavior.

Interactionist Approaches to Social Control

The interactionist methodology, which is closely associated with the labeling theory of crime, holds that endeavors by agencies via social control to prevent delinquency are, ironically, positively correlated with deviance (Becker, 2018).

According to interactionism, crime is a social construct, and stereotypical assumptions pervade the labeling of the purported powerless by the oppressive agents of social control.

The working class are unfairly tattered by the criminal justice system, and are less likely to be able to negotiate the system to their advantage. The police tend to patrol working class areas more which results in the working class crime statistics being higher than middle class.

The working class are often labeled as being more criminogenic and therefore the criminal justice system sees them as making conscious choices to commit crime where as middle class are seen as making a mistake or unintentionally committing a crime.

What supposedly follows is a self-fulfilling prophecy: criminal careers are engendered, and deviancy is amplified. Interactionists contend that individuals become criminals because of the labeling that occurs during their micro-level interactions with the police, and not because of the individual”s social background, or impeded opportunity structures.

Moreover, interactionists argue that some delinquents and criminals escape labeling, but that the powerless generally tend to receive these labels. The theorist’s further demand policies that pretermit labeling minor infractions as deviant.

Hirschi’s Control Theory

Travis Hirschi’s theory posits that deviance and crime are induced by the weakening of an individual’s bonds to society (Hirschi, 1969; Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1983). Strong attachment, conversely, engenders conformity.

Hirschi adduced four types of bonds as the essential constituents of the glue that holds a society together:

-

Attachment

-

Involvement

-

Commitment

-

Belief

The theory implies that single, unemployed, and young males are more prone to delinquency than their older, married, and employed counterparts. Truancy, in particular, seems a potent predictor of deviance.

Hirschi suggests that the underclass are more likely to lack impulse control and bonds to the community which prevent them from committing crime.

Hirschi’s theory has been espoused by significant evidence. Donald West and David Farrington of Cambridge University, for instance, examined 411 working-class men, from their childhood through to their late 30’s (Farrington, 1994).

Their study indicated that delinquents and criminals were likelier to hail from impoverished single-parent households. Moreover, they were more likely to have been subjected to poor parenting and have parents, who themselves had been offenders.

Additionally, Martin Glynn’s research into problems associated with absent fathers has illuminated the consequences of broken familial bonds (Glynn, 2011).

His qualitative survey of a culturally and socially diverse group of 48 young people (22 female and 26 male) aged 16-25 in Liverpool, Derby, and London, suggests that the adverse effects of absent fathers may range from anti-social conduct and crime to drug use and heavy drinking.

FAQs

What are social control mechanisms?

Social control mechanisms regulate the conduct of individuals in a society. They may be categorized as follows:

-

Preventive: the establishment of roles with assigned priorities and the exertion of social pressure to elicit subordination to laws.

-

Restraining: cultural mores and religious obligations that moderate various inclinations.

-

Sanctioning:

-

Economic: boycotts and fines.

-

Physical: expulsion and imprisonment.

-

Psychological: reproofs and ridicule.

-

In addition to the above, government propaganda to effect desired behavioral outcomes via the influence of public opinion deserves mention as well.

What are social control agencies?

Individuals, social institutions, and codes of conduct that seek to prevent or restrain deviance and crime can be described as > agents of social control.

Examples range from parents, older siblings, and neighbors, to police officers, the judiciary, and written constitutions.

While some are informal and exert their influence in subtle and intangible ways, others are formal and communicate their expectations (penalties for insubordination and rewards for obedience) through legal promulgations.

Why is social control difficult in contemporary society?

Today’s increased access to a wealth of information and the proliferation of social media platforms can readily expose a society’s members to opinions and norms manifestly contrary to those of its ruling elites.

This exposure to alternate worldviews (including what must be rightly deemed deviance) can challenge the credibility of a society’s traditional agents of social control, thereby diminishing their capacity to substantially influence the ordinary subjects of society.

The growth of Iran’s and China’s pro-democracy movements that have threatened the heavy-handed rule of their leaders illustrates this development.

Is social control theory macro, or micro?

Social control theory may employ either macro or micro-level analysis. Hirschi’s approach, for instance, closely examines immediate family bonds and the implications of their breakdown for deviance.

Interactionists, likewise, focus on how labeling occurs in micro-level interactions between the would-be-deviants and various agents of social control such as police officers.

The Marxist approach views the phenomenon as a macro-level struggle between an oppressive capitalist ruling class, and a passive and oppressed workforce.

Similarly, Parsons evaluates the roles played by the macro milieus such as the economy and the polity, as constituents of the larger social system containing controls.

What is the difference between strain theory and control theory?

Strain theory holds that individuals are thrust into crime and deviance by stressors or strains imposed upon them by society, whereas control theory attributes deviance and crime to a paucity of bonds or controls.

The two theories occupy distinct ends of the spectrum. Strain theory, for instance, claims that the societal expectation that one be successful in life can lead individuals to engage in illegal activities such as the sale of drugs and stealing.

Control theory, conversely, suggests that such expectations deter crime by channeling individuals’ energies into acceptable forms of employment and the formation of relationships with others.

How is socialization a form of social control?

Socialization involves the internalization of cultural mores and social norms, via both teaching and learning for the attainment of cultural and social continuity.

Parsons, notably, argued that socialization engenders a willingness to submit to a society’s standards for conduct. Socialization can thus, be described as a type of informal (rather than formal) social control.

Socialization hardly includes legal sanctions or imprisonment. However, when it is carried out by families, schools, and religious communities, it does indoctrinate individuals and mold them into citizens obedient to civil laws.

References

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. London: Free Press of Glencoe.

Bowes, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in Captalist America.

Cole, M. (2019). Theresa May, the hostile environment and public pedagogies of hate and threat: The case for a future without borders. Routledge.

Cicourel, Aaron Victor, and John I. Kitsuse. The educational decision-makers . Bobbs-Merrill, 1963.

Gibbs, J. P. (1977). Social control, deterrence, and perspectives on social order. Social Forces, 56 (2), 408-423.

Glynn, M. (2011). Father deficit, young people and substance misuse. London: Addaction.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Key idea: Hirschi’s social bond/social control theory. Key ideas in criminology and criminal justice, 1969, 55-69.

Hirschi, T. (2017). On the compatibility of rational choice and social control theories of crime. In The reasoning criminal (pp. 105-118). Routledge.

Hollingshead, A. B. (April 1941). The Concept of Social Control. American Sociological Review, 6 (2): 217–224.

Farrington, D. P. (1999). Cambridge study in delinquent development [great britain], 1961-1981. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research.

Kaptein, M., & Van Helvoort, M. (2019). A model of neutralization techniques. Deviant Behavior, 40 (10), 1260-1285.

Maruna, S., & Copes, H. (2005). What have we learned from five decades of neutralization research?. Crime and justice, 32, 221-320.

Matza, D. (1964). Berkeley University of California. and Center for the Study of Law and Society. Delinquency and Drift. New York: Wiley.

Parsons, T. (1937). The structure of. Social Action, 491.

Parsons, T. (1972). Culture and social system revisited. Social Science Quarterly, 253-266.

Sampson, R. J. (1986). Crime in cities: The effects of formal and informal social control. Crime and justice, 8, 271-311.

Small, A. W., & Vincent, G. E. (1894). An introduction to the study of society. American Book Company.

Sykes, G. M., & Matza, D. (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American sociological review, 22 (6), 664-670.

Young, K. (1927). Source book for social psychology.