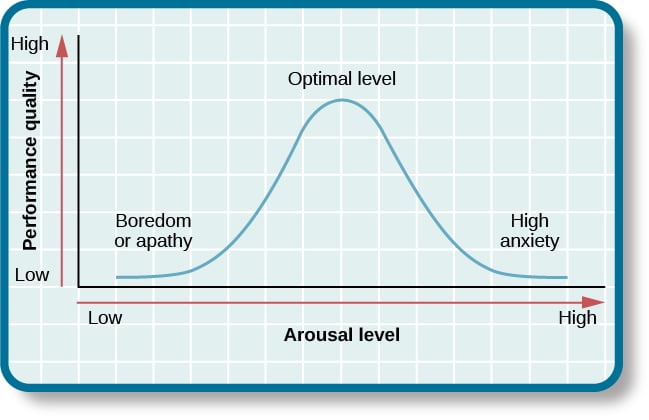

The concept of optimal arousal in relation to performance on a task is depicted here. Performance is maximized at the optimal level of arousal, and it tapers off during under- and overarousal.

Key Takeaways

- The Yerkes-Dodson law states that there is an empirical relationship between stress and performance and that there is an optimal level of stress corresponding to an optimal level of performance. Generally, practitioners present this relationship as an inverted U-shaped curve.

- Research shows that moderate arousal is generally best; when arousal is very high or very low, performance tends to suffer (Yerkes & Dodson, 1908).

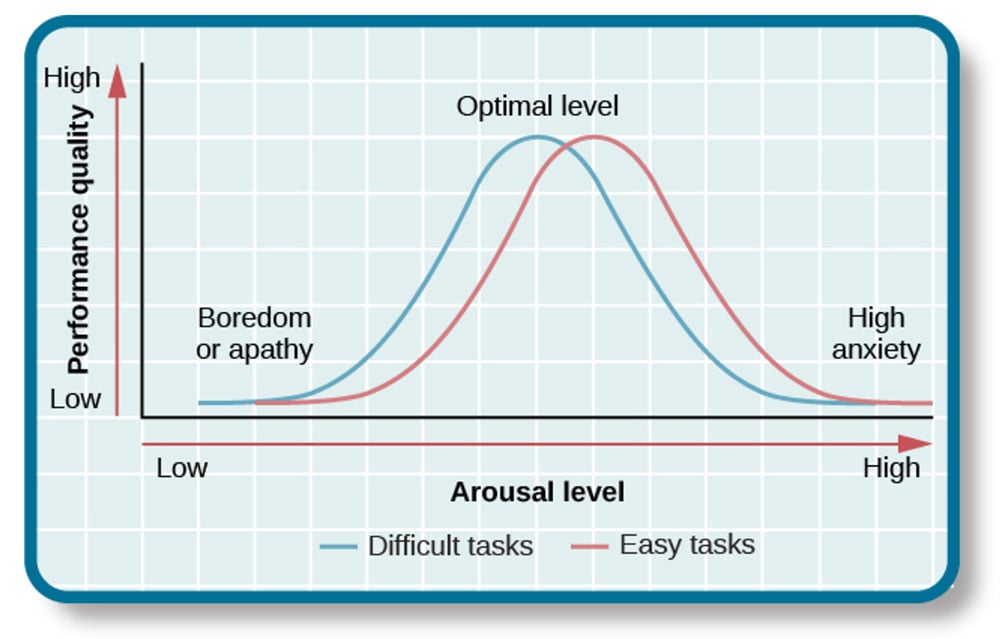

- Robert Yerkes (pronounced “Yerk-EES”) and John Dodson discovered that the optimal arousal level depends on the complexity and difficulty of the task to be performed.

- This relationship is known as the Yerkes-Dodson law, which holds that a simple task is performed best when

arousal levels are relatively high, and complex tasks are best performed when arousal levels are lower. - The Yerkes-Dodson law’s original formulation derives from a 1908 paper on experiments in Japanese dancing mice learning to discriminate between white and black boxes using electric shocks. This research was largely ignored until the 1950s when Hebb’s concept of arousal and the “U-shaped curve” led to renewed interest in the Yerkes-Dodson law’s general applications in human arousal and performance.

- The Yerkes-Dodson law has more recently drawn criticism for its poor original experimental design and it’s over-extrapolated scope to personality, managerial practices, and even accounts of the reliability of eyewitness testimony.

How the Law Works

The Yerkes-Dodson law describes the empirical relationship between stress and performance.

In particular, it posits that performance increases with physiological or mental arousal, but only up to a certain point. This is also known as the inverted U model of arousal.

When stress gets too high, performance decreases. To add more nuance, the shape of the stress-performance curve varies based on the complexity and familiarity of the task.

Task performance is best when arousal levels are in the middle range, with difficult tasks best performed under lower levels of arousal and simple tasks best performed under higher levels of arousal.

Original Experiments

The Yerkes-Dodson law has seen a number of interpretations since its inception in 1908. In their original paper, Robert Yerkes and John Dodson reported the results of two experiments involving “discrimination learning” – the ability to respond differently to different stimuli – and dancing mice (Teigen, 1994).

The mice received a non-injurious electric shock whenever they entered a white box but no shock when they entered the black box next to the white box.

In the first set of experiments, Yerkes and Dodson gave the mice very weak shocks; however, they found that these mice took two long to learn the habit of choosing the black box over the white box (choosing correctly 10/10 times over three consecutive days).

When the researchers increased the strength of the shock, the number of trials needed for the mice to learn the habit decreased – until they reached the third and strongest level of electric shock.

When the electric shock was at its strongest, the number of trials needed for the mice to learn which box to enter went up again. This finding went against Yerkes and Dodson” hypothesis that the rate of habit-formation would increase linearly with the increasing strength of the electric shock.

Instead, a degree of stimulation that was neither too weak nor too strong optimized the rate of learning (Yerkes and Dodson, 1908; Teigan, 1994).

Because of this unexpected result, Yerkes and Dodson elaborated on their original experimental design to provide “a more exact and thoroughgoing examination of the relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of learning” (1908).

The researchers made it easier to discriminate between the white and black boxes by letting more light into the white box and used five rather than three levels of shock.

Contrary to what we now know as the Yerkes-Dodson law, the weakest stimulus gave the slowest rate of learning, while the strongest stimulus led to the fastest rate of learning.

This confused Yerkes and Dodson, who wrote, “The results of the second set of experiments contradict those of the first set. What does this mean?” (1908).

One hypothesis the researchers made was that these contradictory results came from the easiness of the discrimination task.

To test this hypothesis, Yerkes and Dodson made the discrimination task more difficult than in the first set of experiments by allowing less light into the white and black boxes.

The researchers used four levels of shock, but fewer mice in each condition than before – two rather than four. In this set of experiments, the most efficient learning seemingly occurred at the second-weakest shock level (Teigen, 1994).

From these three sets of experiments, Yerkes and Dodson concluded that both weak and strong stimuli can result in low rates of habit formation and that the stimulus level most conducive to learning depends on the nature of the task.

“As the difficultness of discrimination is increased, the strength of that stimulus which is most favorable to habit-formation approaches the threshold” (Yerkes and Dodson, 1908; Teigen, 1994).

Replication Studies

Following the original formulation of the Yerkes-Dodson law, researchers replicated the original study, using animals such as chicks (Cole, 1911) and kittens (Dodson, 1915).

Cole (1911) gave chicks an easy, medium, and difficult discrimination task, with four levels of shock for the medium task and three levels of shock for the other tasks.

In the easy task, the rapidity of learning increased with the strength of shock; in the medium-difficulty task, the strongest shock seemingly decreased the rate of learning, and in the difficult task, the strong shock increased the variability of performance – three chicks learned more rapidly due to the strong shock, while two others failed to learn the discrimination task (the sixth chick died over the course of the experiment).

Although Cole (1911) only observed one U-curve (in the medium-difficulty condition), he concluded that his results were in agreement with Yerkes-Dodson.

Dodson (1915), meanwhile, trained four kittens to discriminate between light and dark-colored boxes by giving them a “medium-strength” shock when they entered the darker box.

These kittens performed better at the discrimination task than those given a “strong” electric shock. When the task was made easier (again, by letting more light into the boxes), the strong and medium-strength shocks proved equally effective. With an easier task, learning improved with shock strength (Teigen, 1994).

Dodson himself later found that both the strength of rewards and punishments were related to the rapidity of learning in a U-shaped manner.

For example, rats who had been starved for up to 41 hours prior to the experiment showed higher rates of discrimination learning than those who were not. However, if they were starved longer (and food was more rewarding as a result), learning became less efficient (Dodson, 1917).

Later scholars generally agreed that the Yerkes-Dodson law was about the relationship between punishment and learning.

Young (1936), following a review of the research of Yerkes and Dodson (1908), Cole (1911), and Dodson (1915), added a later confounding study by Vaughn and Diserens (1930) showing that maze learning was more efficient in human subjects given either light or medium punishments in the form of electric shocks, but not with heavy punishment or no punishment.

To quote Young, “For the learning of every activity, there is an optimum degree of punishment” (1936).

The 1930s and 1940s saw an evolution of the Yerkes-Dodson law.

Writers such as Thorndike (1932), Skinner (2019), and Estes (1944) did away with the idea of punishment as a fundamental learning principle, and others introduced a distinction between learning and performance (Teigen, 1994).

Researchers reinterpreted the Yerkes-Dodson law as describing the relationship between motivation and performance.

Some, such as Hilgard and Marquis (1961), concluded that the law was evidence that “under certain conditions, the drive may actually interfere” with learning.

Introductory textbooks as well as scholars on the subject, have described the Yerkes-Dodson law in terms of motivation and performance (e.g., Bourne and Ekstrand, 1973).

In these descriptions, the Yerkes-Dodson law has become more about motivated behavior in general than the psychology of learning.

The shape described by the Yerkes-Dodson law has also changed from U-curves to the inverted U: while learning (as measured by the number of trials needed for mastery) is optimal at the lowest point of a U-curve (the least trials needed), performance is optimal, at its highest, at the highest point of the inverted U-curve.

This expansion in scope, it has been argued, renewed interest in the Yerkes-Dodson law from 1955 to 1960 (Teigen, 1994).

Broadhurst (1957) replicated the original Yerkes-Dodson experiment with a better design by using four motivation levels and three difficulty levels with ten rats in each condition.

Again, the rats had to discriminate between light and dark boxes, but they were motivated by different levels of air deprivation: 0, 2, 4, or 8 seconds.

For the easy discrimination task, the highest performance was seen in the 4-second air deprivation group, while the optimum moved to 2 seconds for the medium and difficult task groups.

Broadhurst also proposed testing motivational differences in individual rats by conducting the experiment on rats differing in “emotionality” (Broadhurst, 1957; Teigen, 1994).

Examples

Eyewitness Testimony

Expert witnesses have cited the Yerkes-Dodson law in court.

Witness for the defense: The accused, the eyewitness, and the expert who puts memory on trial, Elizabeth Loftus, a psychologist and expert witness in memory and the fallibility of memory, eyewitness testimony explains,

“I approached the backboard located in front of the jury box and, with a piece of chalk, drew the upside-down U shape that represented the relationship between stress and memory known to psychologists as the Yerkes-Dodson law” (Loftus and Ketcham, 1991).

Although this curve bore more similarity to Hebb’s inverted U-curve of arousal, Loftus used the curve to relate arousal (or “stress”) to the efficiency of memory (rather than, as has been formulated by others, learning, performance, problem-solving, the efficiency of coping, or another concept).

The Yerkes-Dodson effect states that when anxiety is at low and high levels, eyewitness testimony is less accurate than if anxiety is at a medium level. Recall improves as anxiety increases up to an optimal point and then declines.

When we are in a state of anxiety, we tend to focus on whatever is making us feel anxious or fearful, and we exclude other information about the situation.

If a weapon is used to threaten a victim, their attention is likely to focus on it. Consequently, their recall of other information is likely to be poor.

Work Stress

The Yerkes-Dodson law has seen frequent citations in managerial psychology, particularly as researchers have argued that the increase in work stress levels is a “costly disaster” (Corbett, 2015).

Corbett (2015) examines the lineage of this law in business writing and questions its application, calling it a “folk method.”

In particular, Corbett criticizes how the law has been extrapolated from its initially limited animal experiments to almost every facet of human task performance, with studies examining tasks as unrelated as product development teamwork, piloting aircraft, competing in sports, and solving complex cognitive puzzles.

This has proved, Corbett argues, to create a situation where the law has become so ambiguous as to be unfalsifiable (2015).

Corbett argues that the generally uncritical portrayal of the Yerkes-Dodson law in textbooks has added a veneer of scientific legitimacy to the management practice of increasing work stress levels at a time when more robust research is increasingly showing that increasing levels of work-related stress corresponds to decreasing mental and physical health.

Corbett, taking an argument from Micklethwait and Wooldridge (1996) posits that management theory is generally incapable of self-criticism, has confusing terminology, rarely “rises above common sense,” and is riddled with contradictions (2015).

In response, he suggests that managerial psychology embraces evidence-based managerial practices.

Arousal and Performance

The renewal of interest in the Yerkes-Dodson law in the 1950s corresponded to the introduction of the concept of arousal (Teigen, 1994).

Hebb (1955), who wrote seminally on the concept of arousal, introduced the inverted U-curve to describe the relationship between arousal and performance.

This idea of arousal shifted the idea of “drive” from the body to the brain and could be framed as either a behavioral, physiological, or theoretical concept. Although not referenced in Hebb’s original paper, writers continued to describe the Yerkes-Dodson law in terms of arousal in textbooks and research literature (Teigen, 1994).

These reformulations of the Yerkes-Dodson law have used terms such as fear, anxiety, emotionality, tension, drive, and arousal interchangeably.

For example, Levitt (2015) holds that the Yerkes-Dodson law describes “that the relationship between fear, conceptualized as drive, and learning is curvilinear,” reporting findings on human maze learning as support for his view.

Using the arousal concept in the formulation of the Yerkes-Dodson law has also seen the law being linked to phenomena such as personality traits and the effects of physiological stimulants.

For instance, in accounting for the theoretical differences in intellectual performance between introverts and extroverts under time pressure, different noise conditions, and at different times of day (e.g., Revelle, Amaral, and Turriff, 1976; Geen, 1984; and Matthews, 1985) as well as participants differing in impulsivity working under the influence of caffeine (e.g., Anderson and Revelle, 1983).

Critical Evaluation

Yerkes and Dodsons’ original experimental design, scholars generally agree, was deeply flawed by modern standards – so much so that W. P. Brown wrote that the law should be “buried in silence” (Teigen, 1994; W. P. Brown, 1965).

Yerkes and Dodsons’ performance vs. stimulus curves were based on averages from just 2-4 subjects per condition; the researchers performed no statistical tests (Gigerenzer and Murray, 2015), and the highest level of shock used in 3, 4, and 5 shock conditions were of different strengths.

The authors assumed that the linear response curve in the second set of experiments (with the easily discriminated white and black boxes) was simply the first part of a U-curve, which would have been fully uncovered given that they had subjected the mice to higher levels of shocks (Teigen, 1994).

Indeed, this experimental design has been misreported by later scholars, such as Winton (1987), who described the original study as a 3 x 3 design with three different levels of discrimination difficulty and three levels of shock strength.

Additionally, Yerkes and Dodson, as Teigen (1994) points out, failed to discuss the concepts involved in the speed of habit formation. Several of the original replicating studies, such as Dodson’s kitten experiment (1915), also showed poor experimental design.

In this experiment, there were only two kittens in the “less difficult” and “easy” discrimination conditions and no U-curves. Nonetheless, Dodson concluded that the results were compatible with the original Yerkes-Dodson experiment (Teigen, 1994).

References

Anderson, K. J., & Revelle, W. (1983). The interactive effects of caffeine, impulsivity and task demands on a visual search task. Personality and Individual Differences, 4(2), 127-134.

Bourne, L. E., & Ekstrand, B. R. (1973). Psychology: Its principles and meanings (Dryden, Hinsdale, IL).

Broadhurst, P. L. (1957). Emotionality and the Yerkes-Dodson law. Journal of experimental psychology, 54(5), 345.

Brown, W. P. (1965). The Yerkes-Dodson law repealed. Psychological reports, 17(2), 663-666.

Cole, L. W. (1911). The relation of strength of stimulus to rate of learning in the chick. Journal of Animal Behavior, 1(2), 111.

Corbett, M. (2015). From law to folklore: work stress and the Yerkes-Dodson Law. Journal of Managerial Psychology.

Dodson, J. D. (1915). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation in the kitten. Journal of Animal Behavior, 5(4), 330.

Dodson, J. D. (1917). Relative values of reward and punishment in habit formation. Psychobiology, 1(3), 231.

Estes, W. K. (1944). An experimental study of punishment. Psychological Monographs, 57(3), i.

Geen, R. G. (1984). Preferred stimulation levels in introverts and extroverts: Effects on arousal and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6), 1303.

Gigerenzer, G., & Murray, D. J. (2015). Cognition as intuitive statistics. Psychology Press.

Hebb, D. O. (1955). Drives and the CNS (conceptual nervous system). Psychological review, 62(4), 243.

Hilgard, E. R., & Marquis, D. G. (1961). Hilgard and Marquis” conditioning and learning.

Levitt, E. E. (2015). The psychology of anxiety.

Loftus, E., & Ketcham, K. (1991). Witness for the defense: The accused, the eyewitness, and the expert who puts memory on trial. Macmillan.

Matthews, G. (1985). The effects of extraversion and arousal on intelligence test performance. British Journal of Psychology, 76(4), 479-493.

Revelle, W., Amaral, P., & Turriff, S. (1976). Introversion/extroversion, time stress, and caffeine: Effect on verbal performance. Science, 192(4235), 149-150.

Skinner, B. F. (2019). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. BF Skinner Foundation.

Teigen, K. H. (1994). Yerkes-Dodson: A law for all seasons. Theory & Psychology, 4(4), 525-547.

Thorndike, E. L. (1932). The fundamentals of learning.

Vaughn, J., & Diserens, C. M. (1930). The relative effects of various intensities of punishment on learning and efficiency. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 10(1), 55.

Winton, W. M. (1987). Do introductory textbooks present the Yerkes-Dodson Law correctly?. American Psychologist, 42(2), 202.

Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation. Punishment: Issues and experiments, 27-41.

Young, P. T. (1936). Social motivation.