Anxious attachment, also referred to as ambivalent attachment, is a relationship style characterized by a persistent concern that one’s longing for intimacy may not be reciprocated.

Individuals with anxious attachment exhibit a strong preoccupation with the availability and responsiveness of their significant others, be it parents, friends, or romantic partners. They yearn for closeness but experience unease regarding whether their emotional needs will be met.

Autonomy and independence can trigger anxiety within them, leading to further distress. Moreover, they may interpret recognition and appreciation from others as insincere or insufficient, exacerbating their insecurities.

Those with anxious attachments typically hold a negative self-image while regarding others positively. Consequently, they seek self-acceptance through the pursuit of approval and validation within their relationships.

They have a higher need for contact and intimacy, which can present challenges for those dating individuals with anxious attachment tendencies.

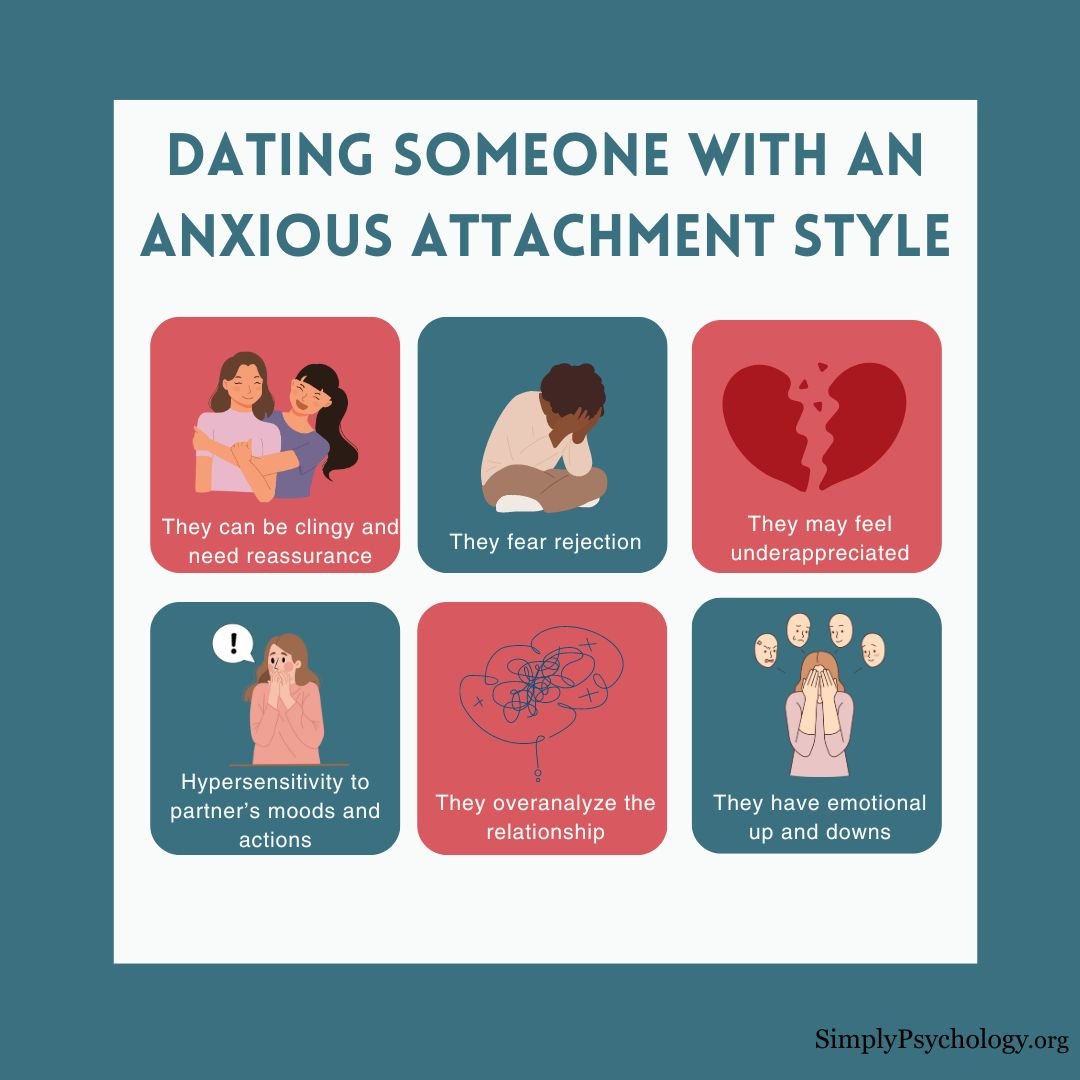

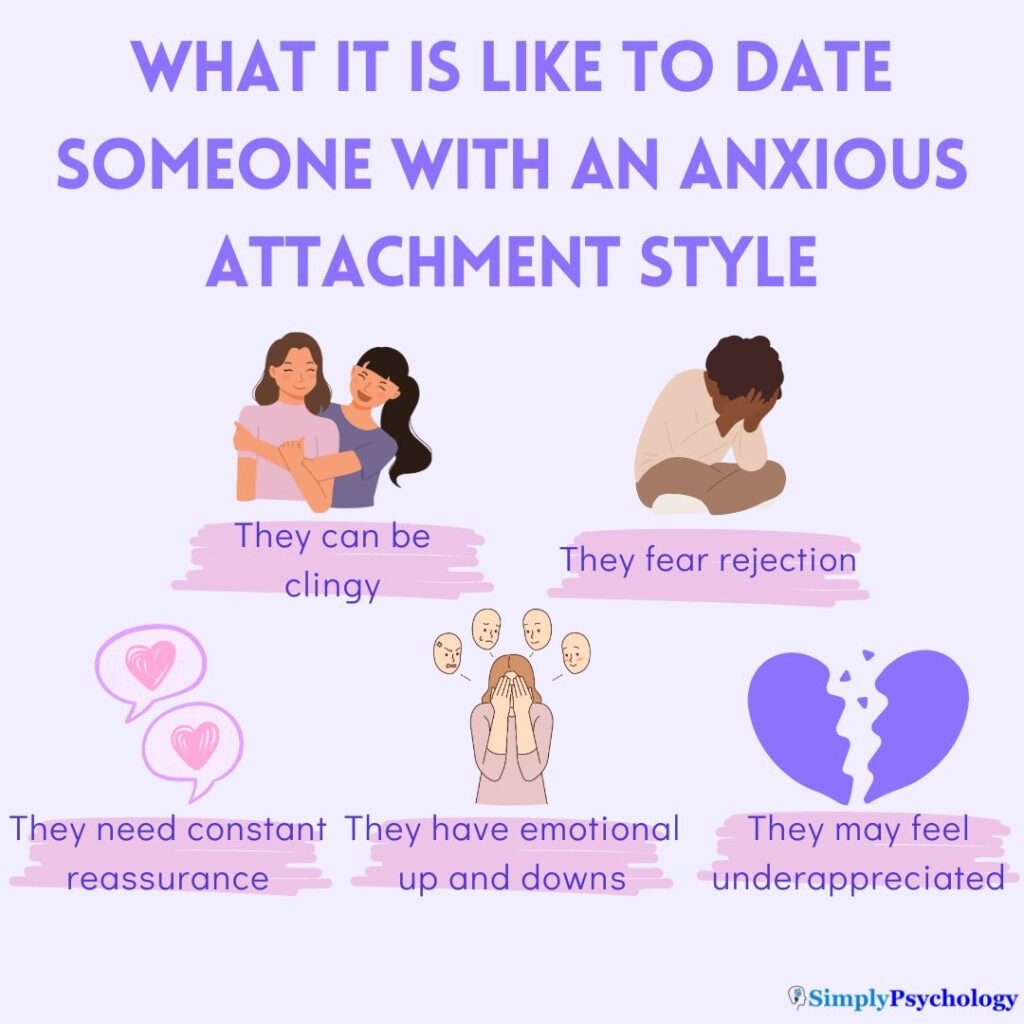

Dating Someone With An Anxious Attachment Style

Romantic relationships with anxious adults can be intense and stressful for the anxious person and their partner.

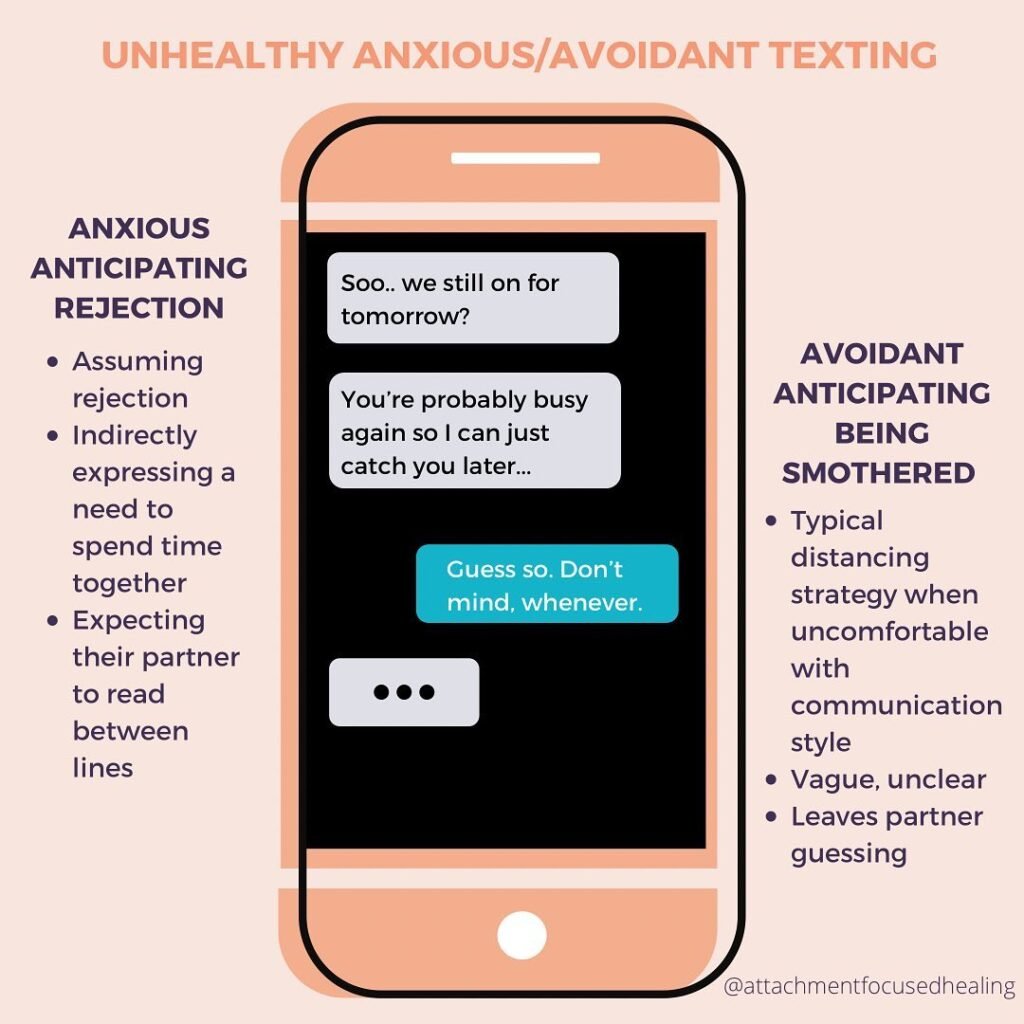

A common theme that is observed is that people with an anxious attachment tend to form relationships with those who have an avoidant attachment style.

Those with an avoidant attachment struggle to commit and feed into anxious attachment anxieties.

Two people with anxious attachment styles can date, but this may present unique challenges that require extra effort and understanding from both partners.

Below are some ways in which an anxious attachment can affect a relationship:

Clinginess

Someone who has an anxious attachment style may become very fixated on a romantic interest. They may desire to jump into relationships very quickly, wanting to commit very fast.

Consequently, they may struggle with long-distance relationships, as this will cause a lot more anxiety.

They may become very preoccupied with their relationship and fall in love easily to the point where they may become ‘obsessed’ with their partner.

They may be more likely to project everything they desire onto one person, which can, in fact, cause anxiety levels to elevate.

Fear of rejection

An anxiously attached adult may constantly be worried about losing their partner or not being able to contact them in times of need.

The slightest disappointment or sign of rejection from a partner could be incredibly harmful to the anxious person’s already low self-esteem.

If a loved one rejects them or fails to respond to their needs, the anxious person may blame themselves and believe they are unworthy of being loved.

A simple text can lead to feelings of resentment or anxiety, especially for those always on guard. Those with anxious attachment often fear rejection, with minor changes in their partner’s behavior triggering alarm.

Conversely, avoidants feel overwhelmed when they sense someone encroaching on their personal space, leading them to distance themselves.

This dynamic can spiral, with the anxious partner seeking more connection and the avoidant wanting distance, creating a continuous push/pull cycle.

Texts can often mislead couples, so it’s crucial to communicate clearly. Anxious individuals should express their needs directly, as avoidants struggle with subtle cues.

Avoidants should recognize their partner’s emotional needs as valid.

Recognizing personal triggers can help curb unhealthy communication, prompting more thoughtful interactions.

Need for constant reassurance

Due to the anxiously attached person feeling extremely insecure and having low self-worth, they may turn to their partner for reassurance.

While it is normal to want reassurance, an anxious person may be persistent in their attempts to seek reassurance from the partner.

This can put a strain on the relationship if the partner constantly has to prove that the anxious loved one is worthy of love.

Emotional ups and downs

Being in a relationship with someone who has an anxious attachment style can feel like an emotional rollercoaster.

There can be a mixture of high and low emotions meaning that their partner may not know what to expect from one moment to another.

The relationship can often be filled with anxiety, stress, and even unhappiness for those involved.

The partner of an anxious person may have low relationship satisfaction if their partner cannot offer them emotional stability.

Feeling underappreciated

An anxiously attached person may often feel unappreciated and resentful if they do not think they are getting the love they deserve.

They may worry about where they stand in the relationship and whether their partner loves them as much as they do in return.

They may often fantasize about how they want the relationship and desire to always stay in the ‘honeymoon stage.’

If they do not receive the same priority they perhaps had at the start of the relationship, they may become suspicious of their partner. This could lead the relationship to be toxic.

They may accuse their partner of being unappreciative or untrustworthy if they feel their emotional needs are not always met.

How Someone With An Anxious Attachment Shows Love

Someone with an anxious attachment may show they love someone through the following:

- Prioritizing spending quality time together and craving emotional closeness.

- Expressing their love through frequent communication and gestures of affection.

- Being highly attentive to their partner’s needs and going above and beyond to meet them.

- They may struggle with fear of abandonment but demonstrate their love through intense loyalty and dedication.

- Often planning and envisioning a future together, discussing long-term commitments and goals.

- Valuing deep emotional connections and prioritizing open and honest communication.

- Eagerness to resolve conflicts promptly to maintain a harmonious relationship.

- Prioritizing the well-being and happiness of their partner, sometimes at the expense of their own needs.

- Exhibiting a strong desire for physical closeness and intimacy as a way to express their love.

How to date someone with an anxious attachment style

If you have an anxiously attached partner, there are some things you can do to help them:

Understand their attachment style

Learning about attachment theory and getting to know your partner’s attachment style through research can be a good starting point to understanding them better.

Express gratitude

While you may feel as though you are showing your gratitude in your actions, an anxiously attached person may not pick up on this.

Explicitly telling them when you are appreciative of something can make your intentions clearer. It may be helpful to start sentences with ‘I appreciate that you…’ or ‘Thank you for…’

Give attention and reassurance

As anxiously attached people are very insecure and are filled with self-doubt, they will often seek reassurance from you.

However, if you verbally express to them your affection and love, they are more likely to be reassured than if you just assume they know how you feel.

Verbally reassure them that you value them as a partner to help them see that you are committed to the relationship and are willing to accommodate their needs.

Stick to your word

Since people with anxious attachments have trouble trusting others and fear abandonment, it is important to show them that you can be trusted. If you make promises and commitments, ensure that you follow through.

This can also apply when setting boundaries. When doing this, ensure you have clear boundaries and expectations and reinforce them.

A partner who acts as a reliable security figure can restore a sense of felt security and help the anxious person function more securely.

Discover their love language

If you struggle to know how to express your love and gratitude for your anxiously attached partner, you could discover what their love language is.

Once you know what their love language is, you can cater your words and actions to match.

For instance, if your partner’s love language is ‘words of affirmation,’ you can ensure you verbally tell them that you love them and why.

If their love language is ‘physical touch,’ you can incorporate more intimacy and physical closeness to your partner to show you love them.

Couples therapy

Couples therapy can be beneficial for any relationship to help strengthen it. It can be especially helpful for couples where one is anxiously attached and the other has an avoidant attachment.

Couples therapy gives the opportunity to participate in discussion with your partner with the help of a skilled moderator.

They can help your partner and yourself to process any negative thoughts and feelings at the moment and provide tools to communicate with each other outside of the sessions.

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation . Lawrence Erlbaum.

Baldwin, M.W., & Fehr, B. (1995). On the instability of attachment style ratings. Personal Relationships, 2, 247-261.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L.M. (1991). Attachment Styles Among Young Adults: A Test of a Four-Category Model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61 (2), 226–244.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume I. Attachment . London: Hogarth Press.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (p. 46–76). The Guilford Press.

Brennan, K. A., & Shaver, P. R. (1995). Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21 (3), 267–283.

Caron, A., Lafontaine, M., Bureau, J., Levesque, C., and Johnson, S.M. (2012). Comparisons of Close Relationships: An Evaluation of Relationship Quality and Patterns of Attachment to Parents, Friends, and Romantic Partners in Young Adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 44 (4), 245-256.

Hazan, C., & Shaver, P. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52 (3), 511–524.

Main, M., Kaplan, N., & Cassidy, J. (1985). Security in infancy, childhood and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In I. Bretherton & E. Waters (Eds.), Growing points of attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50 (1-2), 66-104.

Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective development in infancy . Ablex Publishing.

Waters, E., Merrick, S., Treboux, D., Crowell, J., & Albersheim, L. (2000). Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 71 (3), 684-689.